Ariel Malka believes we’ve been thinking about words the wrong way.

With the screens of smartphones, tablets, and e-readers supplanting paper and ink as the primary place where we do our reading, we’ve mostly focused on how to make text look good on our screens. But with a smartphone in almost every pocket, readers now have the ability to do more than just read text—they can interact with it.

Why have we remained limited to sentences and paragraphs, when we can play with text in curves and planes, bend and tinker to see how it folds and responds to different placements in an abstract space and time? This is the basis for Malka’s Chronotext experiments, a more-than-decade-old series of passion projects that are devoted to exploring the unlocked potential of text in the digital world.

“People read or write documents, read or write emails, and mostly read or write through the browser,” says Malka. “The electronic medium added some major improvements, like the infinitely-long scrolling viewport and the hyperlinks, but I would like to challenge these predefined and over-used constructs by exploring all the possible dimensions.”

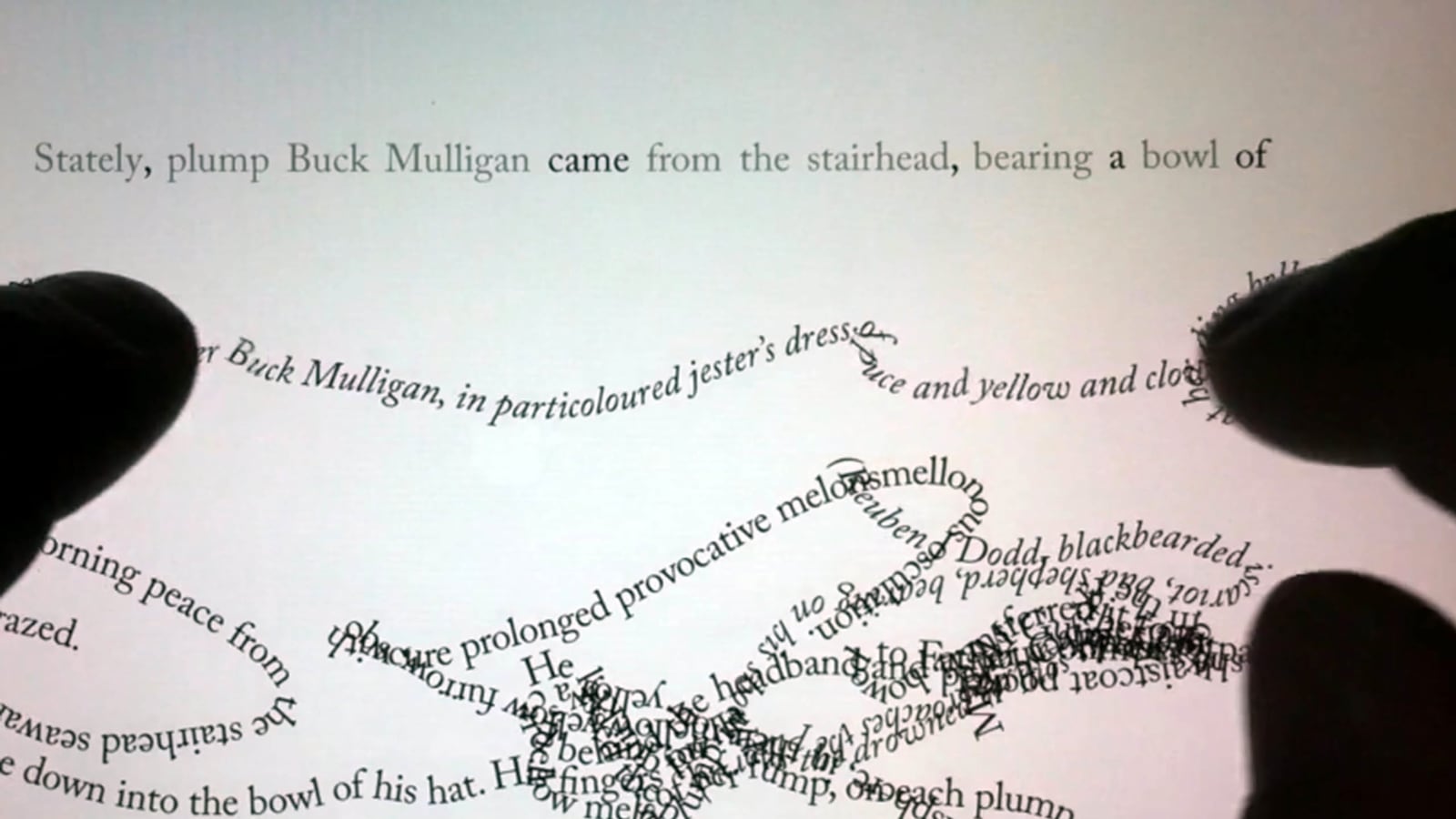

The latest of these projects is the recently released He Liked Thick Word Soup, an app that invites users to literally finger-wrestle with the text of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

It’s an interesting project in a series of interesting projects, but noteworthy for its inherent idealism. In an arena full of products that prioritize speed and efficiency above all else, here is an app that asks you to not just read one of our most difficult, rewarding classics, but to physically sift through it. To do something slower than reading. To do something only possible through technology.

“I obviously believe that slowing down, leaving room for mistakes, taking the time to explore, etc., is the way to go, but that's usually not the approach of the average businessman or startup entrepreneur,” says Malka. “It's more the approach of an artist, an intellectual or a philosopher, which raises another question: Is technology mostly in the hand of entrepreneurs nowadays?”

Malka’s question takes on an additional layer of relevance when one considers his work in light of the Slow Web movement. An offshoot of a larger, more general movement that values slowing down the rapid pace of life, the Slow Web philosophy, as noted by writer Jack Cheng, values timeliness over real-time. It’s letting your pace drive technology, as opposed to technology driving you.

It’s that latter notion that Malka is referring to when he asks if tech is mostly in the hands of the corporate world. According to Jennifer Rauch, who has run the blog Slow Media since 2009, that external pressure has left us in a compromised position in which we are poorly situated to try to answer such questions.

“I think for a lot of people, their use of media is tied to job productivity, so they're sort of scared to disengage, because it can have financial and professional consequences,” says Rauch. “I think the prospects are great for Slow Media in all of these small ways, but the difficulty is in bringing them all together into one sort of coherent movement which—I don’t know if that'll ever happen, or if it even needs to happen.”

Most of the concerns of the Slow Web/Media movement involve quality-of-life concerns: less time in front of screens, more time interacting with others, and compensating for atrophied focus and attention spans. If those are your goals, the tools to achieve them are present, and growing every day. But they’re often reactionary, holding that tech has had a negative impact on how we think, offering alternatives instead of trying to fix that—perhaps with projects like Malka’s.

But according to startup-founder-turned-fiction-writer Jack Cheng, throwing more tech at a tech problem isn’t always the most effective approach.

“The point is that we can build all this tech with a good intent, we can even create things with the intent of slowing us down, making it easier to disconnect,” says Cheng. “But I wonder if the source of the problem is that reaction, the instinct of 'we need to build something to solve this.’”

Perhaps it’s good then, that Ariel Malka is not trying to solve a problem. Rather, he considers himself an explorer, someone with technical skills and artistic ideals challenging long-established conventions. He prefers to create and leave the pondering for others to do. But when asked about the potential for growth in tech projects like his—digital experiments that ask the user to consider things slowly and carefully—he isn’t very bullish.

“In general, most of my colleagues are not going in that direction,” Malka says. “Why? I think that you need a very deep technical and cultural mastery before proposing to change the rules of a given system. And currently, most programmers have no design or cultural agenda. On the other side, the usual artist/intellectual/philosopher has no programming skills, which, in today’s world translates to a limited capability to influence.”