This is how the most dramatic scene of The First Circle, the most famous novel of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, begins:

“One of the wooden booths outside the station was empty but seemed to have a broken window. Innokenty walked on, into the station. Here the four booths set into the wall were all occupied. But in the one to the left, a rough-looking character, not quite sober, was finishing his call and hanging up the receiver. He smiled at Innokenty and started to say something. Innokenty took his place in the booth, carefully pulled the thick-paned door closed, and held it shut with one hand; the other, still gloved, trembled as it dropped a coin into the slot and dialed the number.

After several prolonged buzzes the receiver was lifted at the other end.

“Is this the secretariat?” Innokenty asked, trying to disguise his voice.

“Yes.”

“Please put me through to the Ambassador immediately.”

The answer came in very good Russian.

“I can’t call the Ambassador. What is your business?”

“Give me the charge then! Or the military attache! Please be quick!”

The novel is set in winter Moscow of 1949, and Innokenty was a disenchanted Soviet Foreign Ministry official desperate to trust the Americans with a secret. After much delay, he conveys the message to the U.S. Air Force attache: “This is a life-and-death matter for your country! And not only your country! Listen! Within the next few days a Soviet agent called Georgy Koval will pick something up at a shop selling radio parts; the address is—,” and then he finally made himself crystal clear, “In a few days’ time the Soviet agent Koval will be given important technical information about the production of the atomic bomb, at a radio shop.”

The Soviet Union was desperately trying to catch up with the United States in producing the most deadly weapon on the planet, and Solzehnityn’s story was based on reality. A Soviet diplomat had rung the U.S. embassy, Stalin’s security services intercepted the call, recorded the conversation and sent the recordings to identify a caller to a secret research facility manned by secret services, known as Sharashka or Marfino. The research in Sharashka was conducted by imprisoned engineers, heavily guarded. One of those engineers was Solzhenitsyn.

This story started a chain of events, crucial to the Cold War history. It inspired Solzhenitsyn to write his very first novel. His closest friend in Marfino, Lev Kopelev, who was tasked to identify the voice of a caller, was to become a famous dissident, a flamboyant intellectual, respected in many circles of the Moscow intelligentsia. Kopelev got Solzhenitsyn his first major publication in a Soviet journal, using his connections to bring One Day of Ivan Denisovich to the attention of the editors of Novy Mir. In 1968, one of Kopelev’s relatives was one of eight people in Red Square to protest the invasion of Czechoslovakia, the most famous event in the history of the Soviet dissident movement.

The episode in Marfino had a huge impact on secret services, too. The research that had led to the identification of the traitor was carefully preserved and transferred to another Sharaskha in Kuchino, which was to become the birthplace of the Russian system of Internet surveillance, SORM (I recount this story in my latest book, The Red Web).

But there was a spy in The First Circle, and this spy was real.

Solzhenitsyn carefully changed all names, except for the betrayed Soviet spy, Koval — apparently he thought the imprisoned engineers would have never given a real name of a betrayed spy by their masters. As it turned out, he was wrong.

George Koval was a U.S. citizen born in Iowa in 1913 to a family of Jewish emigres who fled the Russian Empire. In 1932, his family was lured by IKOR, the Organization for Jewish Colonization in Russia, to get back into what was now the Soviet Union. Koval moved with his family. He joined the Moscow Technical Chemical Institute, was quickly recruited by Soviet military intelligence and sent back to the United States in 1940. His code name was to be Delmar.

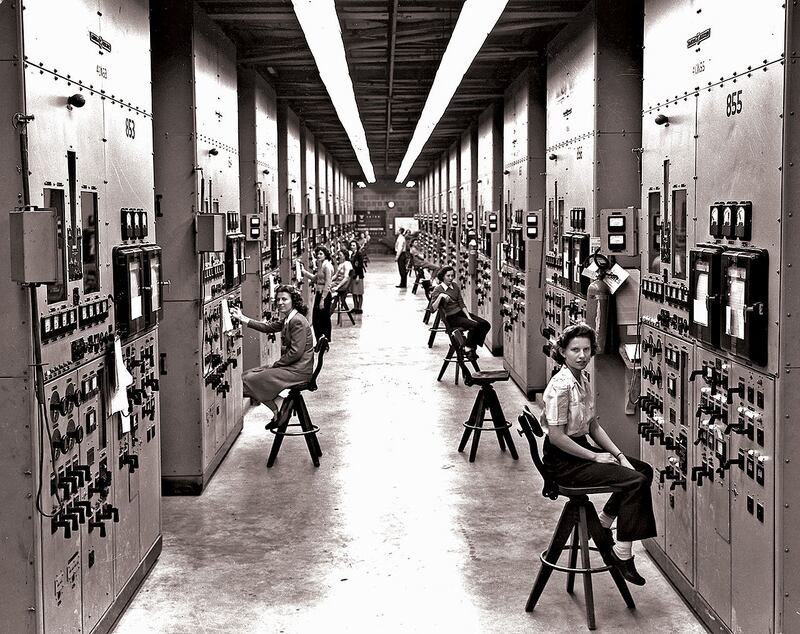

For three years Koval worked for an electric company run by a Soviet agent. Then, in 1943, he was drafted into the U.S. Army. He was sent for special wartime training at City College in Manhattan. The Manhattan Project was suffering manpower shortages and asked the Army for technically adept recruits. In 1944, Koval was assigned to the top secret atomic bomb program headquartered at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The confidential FBI report stated, “Koval was very popular among servicemen and also students… as indication of his popularity, he was elected either president of his class or a member of an honorary fraternity.”

Koval proved to be a very successful Soviet spy. He penetrated one of the most sensitive sectors of the U.S. government at the time and smuggled out vital secrets that led directly to the Soviet acquisition of the bomb.

In 1949, Koval went back to the Soviet Union, and almost at once was discharged from the military intelligence as private, for reasons still unknown, possibly having to do with an intercepted phone call. He had nothing to do but to join the Moscow Technical Chemical Institute he had graduated from before the war. He spent decades there as a chemist, surrounded by students (his portrait still hangs there on the wall among those of other prominent professors).

In 1999, desperate with his small state pension, Koval approached the U.S. embassy in Moscow and, amazingly, applied for his U.S. pension. He heard somewhere that all who had served in American army during the Second World War could apply for a special social security benefits, and, well, he had served for three years, from 1943 to 1946. The embassy was astonished. The FBI file on Koval was carefully preserved in the agency and his espionage was bureau lore.

In February 2000 Koval got a reply from the Social Security Administration’s Office of Central Operations, in Baltimore. It contained one sentence: “We are writing to tell you that you do not qualify for retirement benefits.”

In 2000, the GRU suddenly decided to honor one of their top wartime spies. Koval was solemnly awarded with a medal “for the service in military intelligence” at the GRU. That year, he gathered his pupils for some sort of celebration and finally admitted that he was a Russian spy in the 1940s.

Yuri Lebedev, a white-bearded man with a look of a typical Russian scientist, was Koval’s closest pupil in the Moscow Technical Chemical Institute. For years, Lebedev was intrigued by Koval’s murky past, but was never able to ask him a direct question about it. Now, at a celebration with only close personal friends, he thought the time was right and brought up The First Circle and Solzhenitsyn. Koval only grinned. “How did he learn all that?” was his only remark.

In January 2006, the Solzhenitsyn’s debut novel was turned into television series and broadcast on Russian TV. The very next day after its airing, George Koval died. He was 93.

Posthumously, he was made a Hero of the Russian Federation, the highest honorary title that can be bestowed on a Russian citizen. In 2007, during his visit to the new headquarters of the GRU, Russian President Vladimir Putin named Koval “the only Soviet intelligence officer” to infiltrate the Manhattan Project.

What it’s still unknown is what happened to the man who was Solzhenitsyn’s model for Innokenty. He was arrested, after all, but his fate is still a mystery.

In contemporary Russia, it’s highly unlikely that the truth will ever emerge.