H.L. Mencken is perhaps our most celebrated journalist. Among the best books he wrote, and certainly one of the most timeless, was Newspaper Days, a memoir about his early years as a Baltimore reporter and editor at the turn of the century. The book is part of The Days Trilogy (in between Happy Days and Heathen Days), newly published by the Library of America in a handsome single volume that includes 200 pages of additional commentary by Mencken. According to Marion Elizabeth Rodgers, who edited this collection, Mencken’s “Notes, Additions and Corrections” were “written mainly between 1943 and 1946, with perhaps a few entries after that up to 1948. Because he was writing about people who were still alive, he sealed these papers under time lock, not to be opened until 25 years after his death, which turned out to be in 1981. As he put it, ‘the passage of time would release all confidences and the grave close over all tender feelings.’”

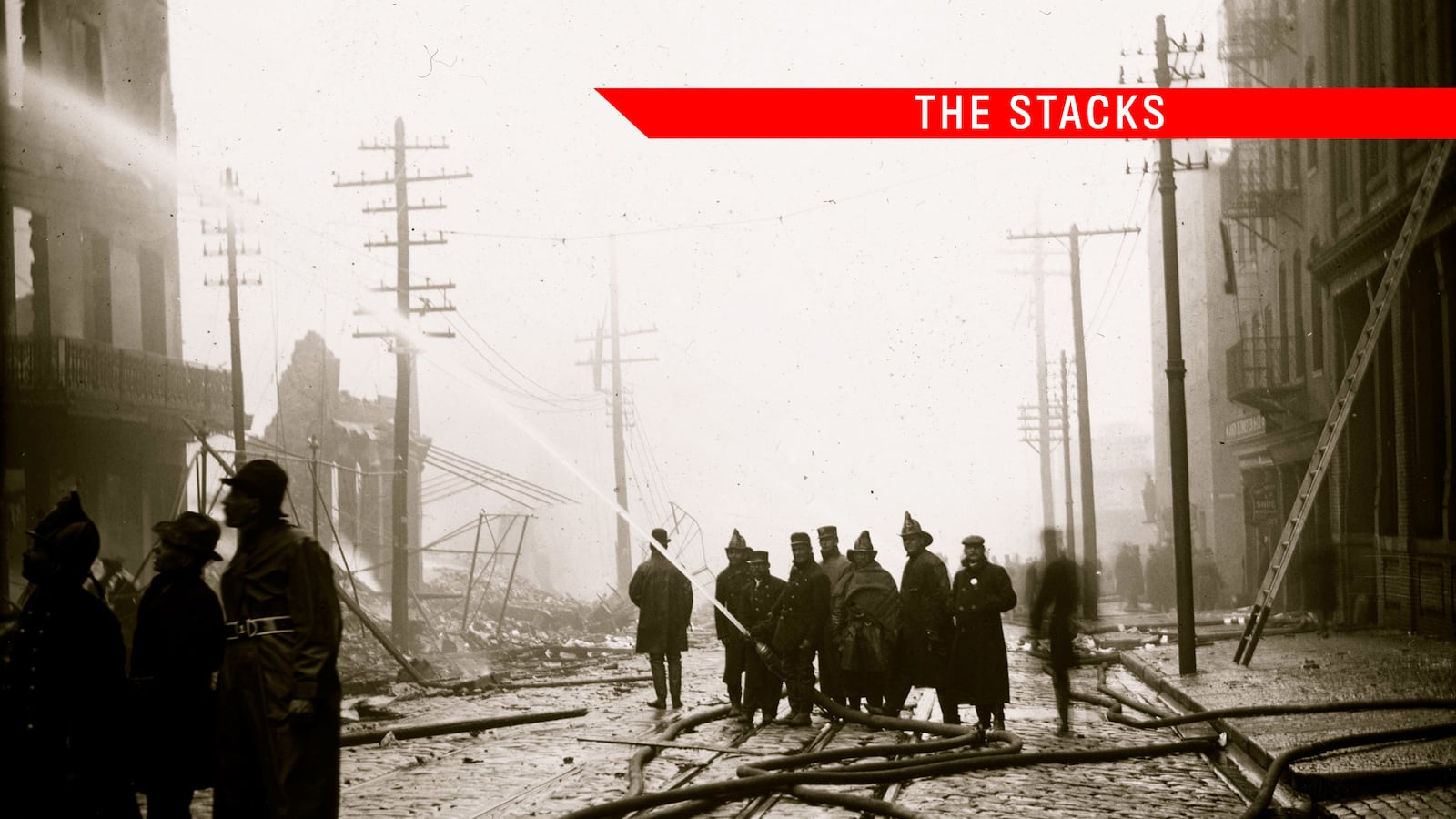

Published for the first time with Mencken’s addenda, The Days Trilogy is better than ever. Take for instance this gem of a story written about the horrific Baltimore fire of 1904. What follows contains two sets of notes—those that accompanied the first edition of Newspaper Days, as well as the additional notes that were released posthumously.

Dig in and relish this treat, made possible with permission from The Library of America; Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC; and the Enoch Pratt Free Library.

At midnight or thereabout on Saturday, February 6, 1904, I did my share as city editor to put the Sunday Herald to bed, and then proceeded to Junker’s saloon to join in the exercises of the Stevedores’ Club. Its members, having already got down a good many schooners, were in a frolicsome mood, and I was so pleasantly edified that I stayed until 3:30. Then I caught a night-hawk trolley-car, and by 4 o’clock was snoring on my celibate couch in Hollins Street, with every hope and prospect of continuing there until noon of the next day. But at 11 a.m. there was a telephone call from the Herald office, saying that a big fire had broken out in Hopkins Place, the heart of downtown Baltimore, and 15 minutes later a reporter dashed up to the house behind a sweating hack horse, and rushed in with the news that the fire looked to be a humdinger, and promised swell pickings for a dull winter Sunday. So I hoisted my still malty bones from my couch and got into my clothes, and 10 minutes later I was on my way to the office with the reporter. That was at about 11:30 a.m. of Sunday, February 7. It was not until 4 a.m. of Wednesday, February 10, that my pants and shoes, or even my collar, came off again. And it was not until 11:30 a.m. of Sunday, February 14—precisely a week to the hour since I set off —that I got home for a bath and a change of linen.

For what I had walked into was the great Baltimore fire of 1904, which burned a square mile out of the heart of the town and went howling and spluttering on for 10 days. I give the exact schedule of my movements simply because it delights me, in my autumnal years, to dwell upon it, for it reminds me how full of steam and malicious animal magnetism I was when I was young. During the week following the outbreak of the fire, the Herald was printed in three different cities, and I was present at all its accouchements, herding dispersed and bewildered reporters at long distance and cavorting gloriously in strange composing rooms. My opening burst of work ran to 64-and-a-half hours, and then I got only six hours of nightmare sleep, and resumed on a working schedule of from 12 to 14 hours a day, with no days off and no time for meals until work was over. It was brain-fagging and back-breaking, but it was grand beyond compare—an adventure of the first chop, a razzle-dazzle superb and elegant, a circus in 40 rings. When I came out of it at last I was a settled and indeed almost a middle-aged man, spavined by responsibility and aching in every sinew, but I went into it a boy, and it was the hot gas of youth that kept me going. The uproar over, and the Herald on an even keel again, I picked up one day a volume of stories by a new writer named Joseph Conrad, and therein found a tale of a young sailor that struck home to me as the history of Judas must strike home to many a bloated bishop, though the sailor naturally made his odyssey in a ship, not on a newspaper, and its scene was not a provincial town in America, but the South Seas. Today, so long afterward, I too “remember my youth and the feeling that will never come back any more—the feeling that I could last forever, outlast the sea, the earth, and all men… Youth! All youth! The silly, charming, beautiful youth!”

Herald reporters, like all other reporters of the last generation, were usually late in coming to work on Sundays, but that Sunday they had begun to drift in even before I got to the office, and by 1 o’clock we were in full blast. The fire was then raging through a whole block, and from our fifth-floor city room windows it made a gaudy show, full of catnip for a young city editor. But the Baltimore firemen had a hundred streams on it, and their chief, an old man named Horton, reported that they would knock it off presently. They might have done so, in fact, if the wind had not changed suddenly at 3 o’clock, and begun to roar from the west. In 10 minutes the fire had routed Horton and his men and leaped to a second block, and in half an hour to a third and a fourth, and by dark the whole of downtown Baltimore was under a hail of sparks and flying brands, and a dozen outlying fires had started to eastward. We had a story* (see Notes), I am here to tell you! There have been bigger ones, of course, and plenty of them, but when and where, between the Chicago fire of 1871 and the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, was there ever one that was fatter, juicier, more exhilarating to the journalists on the actual ground?

Every newspaper in Baltimore save one was burned out, and every considerable hotel save three, and every office building without exception. The fire raged for a full week, helped by that bitter winter wind, and when it fizzled out at last the burned area looked like Pompeii, and up from its ashes rose the pathetic skeletons of no less than 20 overtaken and cremated fire-engines—some of them from Washington, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and New York. Old Horton, the Baltimore fire chief, was in hospital, and so were several hundred of his men.

My labors as city editor during that electric week were onerous and various, but for once they did not include urging lethargic reporters to step into it. The whole staff went to work with the enthusiasm of crusaders shinning up the walls of Antioch, and all sorts of volunteers swarmed in, including three or four forgotten veterans who had been fired years before, and were thought to have long since reached the dissecting room. Also, there were as many young aspirants from the waiting list, each hoping for his chance at last, and one of these, John Lee Blecker by name, I remember brilliantly, for when I told him to his delight that he had a job and invited him to prove it he leaped out with exultant gloats—and did not show up again for five days. But getting lost in so vast a story did not wreck his career, for he lived to become, in fact, an excellent reporter, and not a few old-timers were lost, too. One of the best of them, sometime that afternoon, was caught in a blast when the firemen began dynamiting buildings, and got so coagulated that it was three days before he was fit for anything save writing editorials. The rest not only attacked the fire in a fine frenzy, but also returned promptly and safely, and by 4 o’clock thirty typewriters were going in the city room, and my desk was beginning to pile high with red-hot copy.

Lynn Meekins, the managing editor, decided against wasting time and energy on extras. We got out two, but the story was too big for such banalities: It seemed like a toy balloon in a hurricane. “Let us close the first city edition,” he said, “at 9 o’clock. Make it as complete as you can. If you need 20 pages, take them. If you need 50, take them.” So we began heaving copy to the composing-room, and by 7 o’clock 384 newspaper days there were columns and columns of type on the stones, and picture after picture was coming up from the engraving department. Alas, not much of that quivering stuff ever got into the Herald, for a little before 9 o’clock, just as the front page was being made up, a couple of excited cops rushed in, howling that the buildings across the street were to be blown up in 10 minutes, and ordering us to clear out at once. By this time there was a fire on the roof of the Herald Building itself, and another was starting in the pressroom, which had plate-glass windows reaching above the street level, all of them long ago smashed by flying brands. We tried to parley with the cops, but they were too eager to be on their way to listen to us, and when a terrific blast went off up the street Meekins ordered that the building be abandoned.

There was a hotel three or four blocks away, out of the apparent path of the fire, and there we went in a dismal procession—editors, reporters, printers and pressmen. Our lovely first edition was adjourned for the moment, but every man-jack in the outfit believed that we’d be back anon, once the proposed dynamiting had been done—every man-jack, that is, save two. One was Joe Bamberger, the foreman of the composing room, and the other was Joe Callahan, my assistant as city editor. The first Joe was carrying page-proofs of all the pages already made up, and galley-proofs of all the remaining type-matter, and all the copy not yet set. In his left overcoat pocket was the front-page logotype of the paper, and in his left pocket were 10 or 12 halftones. The other Joe had on him what copy had remained in the city room, a wad of Associated Press flimsy about the Russian-Japanese war, a copy-hook, a pot of paste, two boxes of copy-readers’ pencils—and the assignment book!

But Meekins and I refused to believe that we were shipwrecked, and in a little while he sent me back to the Herald building to have a look, leaving Joe No. 2 to round up such reporters as were missing. I got there safely enough, but did not stay long. The proposed dynamiting, for some reason unknown, had apparently been abandoned, but the fire on our roof was blazing violently, and the pressroom was vomiting smoke. As I stood gaping at this dispiriting spectacle a couple of large plate-glass windows cracked in the composing room under the roof, and a flying brand—some of them seemed to be six feet long!—fetched a window on the editorial floor just below it. Nearly opposite, in Fayette Street, a 16-story office building had caught fire, and I paused a moment more to watch it. The flames leaped through it as if it had been made of matchwood and drenched with gasoline, and in half a minute they were roaring in the air at least 500 feet. It was, I suppose, the most melodramatic detail of the whole fire, but I was too busy to enjoy it, and as I made off hastily I fully expected the whole structure to come crashing down behind me. But when I returned a week later I found that the steel frame and brick skin had both held out, though all the interior was gone, and during the following summer the burned parts were replaced, and the building remains in service to this day, as solid as the Himalayas.

At the hotel Meekins was trying to telephone to Washington, but long-distance calls still took time in 1904, and it was 15 minutes before he raised Scott C. Bone, managing editor of the Washington Post. Bone was having a busy and crowded night himself, for the story was worth pages to the Post, but he promised to do what he could for us, and presently we were hoofing for Camden Station, a good mile away—Meekins and I, Joe Bamberger with his salvage, a copy-reader with the salvage of the other Joe, half a dozen other desk men, 15 or 20 printers, and small squads of pressmen and circulation men. We were off to Washington to print the paper there—that is, if the gods were kind. They frowned at the start, for the only Baltimore & Ohio train for an hour was an accommodation, but we poured into it, and by midnight we were in the Post office, and the hospitable Bone and his men were clearing a place for us in their frenzied composing room, and ordering the pressroom to be ready for us.[1]

Just how we managed to get out the Herald that night I can’t tell you, for I remember only trifling details. One was that I was the principal financier of the expedition, for when we pooled our money at Camden Station it turned out that 386 newspaper days had $40 in my pocket, whereas Meekins had only $5*, and the rest of the editorial boys not more than $20 among them. Another is that the moon broke out of the winter sky just as we reached the old B & O Station in Washington, and shined down sentimentally on the dome of the Capitol. The Capitol was nothing new to Baltimore journalists, but we had with us a new copy-reader who had lately come in from Pittsburgh, and as he saw the matronly dome for the first time, bathed in spooky moonlight, he was so overcome by patriotic and aesthetic sentiments that he took off his hat and exclaimed “My God, how beautiful!” And a third is that we all paused a second to look at the red glow over Baltimore, 35 miles away as the crow flies. The fire had really got going by now, and for four nights afterward the people of Washington could see its glare from their streets.

Bone was a highly competent managing editor, and contrived somehow to squeeze us into the tumultuous Post office. All of his linotypes were already working to capacity, so our operators were useless, but they lent a hand with the makeup, and our pressmen went to the cellar to reinforce their Post colleagues. It was a sheer impossibility to set up all the copy we had with us, or even the half of it, or a third of it, but we nevertheless got eight or 10 columns into type, and the Post lent us enough of its own matter to piece out a four-page paper. In return we lent the hospitable Post our halftones, and they adorned its first city edition next morning. Unhappily, the night was half gone before Bone could spare us any press time, but when we got it at last the presses did prodigies, and at precisely 6:30 the next morning we reached Camden Station, Baltimore, on a milk train, with 30,000 four-page Heralds in the baggage car. By 8 o’clock they were all sold. Our circulation hustlers had no difficulty in getting rid of them. We had scarcely arrived before the news of our coming began to circulate around the periphery of the fire, and in a few minutes newsboys swarmed in, some of them regulars but the majority volunteers. Very few boys in Baltimore had been to bed that night: The show was altogether too gaudy. And now there was a chance to make some easy money out of it.

Some time ago I unearthed one of these orphan Heralds from the catacombs of the Pratt Library in Baltimore, and gave it a looking over. It turned out to be far from bad, all things considered. The story of the fire was certainly not complete, but it was at least coherent, and three of our halftones adorned Page 1. The eight-column streamer-head that ran across its top was as follows:

HEART OF BALTIMORE WRECKED BYGREATEST FIRE IN CITY’S HISTORY

Well, brethren, what was wrong about that? I submit that many worse heads have been written by pampered copy-readers sitting at luxurious desks, with vassals and serfs at their side. It was simple; it was direct; there was no fustian in it; and yet it told the story perfectly. I wrote it on a makeup table in the Post composing room, with Meekins standing beside me writing a box for the lower right-hand corner of the first page, thanking the Post for its “proverbial courtesy to its contemporaries” and promising formally that the Herald would be “published daily by the best means it can command under the circumstances.”

Those means turned out, that next day, to be a great deal short of ideal. Leaving Joe Callahan, who had kept the staff going all night, to move to another and safer hotel, for the one where we had found refuge was now in the path of the fire, Meekins and I returned to Washington during the morning to make arrangements for bringing out a larger paper. We were not ashamed of our four pages, for even the Sunpaper, printed by the Washington Evening Star, had done no better, but what were four pages in the face of so vast a story? The boys had produced enough copy to fill at least 10 on the first day of the fire, and today they might turn out enough to fill 20. It would wring our gizzards intolerably to see so much good stuff going to waste. Moreover, there was art to consider, for our two photographers had piled up dozens of gorgeous pictures, and if there was no engraving plant left in Baltimore there were certainly plenty in Washington.

But Bone, when we routed him out, could not promise us any more accommodation than he had so kindly given us the first night. There was, it appeared, a longstanding agreement between the Post and the Baltimore Evening News, whereby each engaged to take care of the other in times of calamity, and the News staff was already in Washington cashing in on it, and would keep the Post equipment busy whenever it was not needed by the Post itself. Newspapers in those days had no such plants as they now boast: If I remember rightly, the Post had not more than a dozen linotypes, and none of them could chew up copy like the modern monsters. The prospect seemed depressing, indeed, but Bone himself gave us a shot of hope by mentioning casually that the Baltimore World appeared to have escaped the fire. The World? It was a small, ill-fed sheet of the kind then still flourishing in most big American cities, and its own daily editions seldom ran beyond four pages, but it was an afternoon paper, and we might hire its equipment for the night. What if it had only four linotypes? We might help them out with handset matter. And what if its Goss press could print but 5,000 six- or eight-page papers an hour? We might run it steadily from 6 p.m. to the middle of the next morning, bringing out edition after edition.

We got back to Baltimore as fast as the B & O could carry us, and found the World really unscathed, and, what is more, its management willing to help us, and as soon as its own last edition was off that afternoon Callahan and the gentlemen of the Herald staff came swarming down on its little office in Calvert Street. The ensuing night gave me the grand migraine of my life, with throbs like the blows of an ax and continuous pinwheels. Every conceivable accident rained down on us. One of the linotypes got out of order at once, and when, after maddening delays, Joe Bamberger rounded up a machinist, it took him two hours to repair it, and even then he refused to promise that it would work. Meekins thereupon turned to his desperate plan to go back to Gutenberg and set matter by hand—only to find that the World had insufficient type in its cases to fill more than a few columns. Worse, most of this type appeared to be in the wrong boxes, and such of it as was standing on the stones had been picked for sorts by careless printers, and was pretty well pied.[2]

Meekins sent me out to find more, but all the larger printers of Baltimore had been burned out, and the only supply of any size that I could discover was in the office of the Catholic Mirror, a weekly. Arrangements with it were made quickly, and Joe Bamberger and his gallant lads of the union rushed the place and proceeded to do or die, but setting type by hand turned out to be a slow and vexatious business, especially to linotype operators who had almost forgotten the case. Nor did it soothe us to discover that the Mirror’s stock of type (most of it old and worn) was in three or four different faces, with each face in two or three sizes, and that there was not enough of any given face and size to set more than a few columns. But it was now too late to balk, so Joe’s goons went to work, and by dark we had 10 or 12 columns of copy in type, some of it in eight-point, some in 10-point and some in 12-point. That night I rode with Joe’s chief of staff, Josh Lynch, on a commandeered express wagon as these galleys of motley were hauled from the Mirror office to the World office. I recall of the journey only that it led down a steep hill, and that the hill was covered with ice. Josh howled whenever the horse slipped, but somehow or other we got all the galleys to the World office without disaster, and the next morning, after six or eight breakdowns in the pressroom, we came out with a paper that at least had some news in it, though it looked as if it had been printed by country printers locked up in a distillery.

When the first copy came off the World’s rickety Goss press Meekins professed to be delighted with it. In the face of almost hopeless difficulties, he said, we had shown the resourcefulness of Robinson Crusoe, and for ages to come this piebald issue of the Herald would be preserved in museums under glass, and shown to young printers and reporters with appropriate remarks. The more, however, he looked at it the less his enthusiasm soared, and toward the middle of the morning he decided suddenly that another one like it would disgrace us forever, and announced at once that we’d return to Washington. But we knew before we started that the generous Bone could do no more for us than he had already done, and, with the Star monopolized by the Baltimore Sun, there was not much chance of finding other accommodation in Washington that would be better than the World’s in Baltimore. The pressure for space was now doubled, for not only was hot editorial copy piling up endlessly, but also advertising copy. Hundreds of Baltimore business firms were either burned out already or standing in the direct path of the fire, and all of them were opening temporary offices uptown, and trying to notify their customers where they could be found. Even in the ghastly parody printed in the World office we had made room for nearly three columns of such notices, and before 10 o’clock Tuesday morning we had copy for 10 more.

But where to turn? Wilmington in Delaware? It was nearly 70 miles away, and had only small papers. We wanted accommodation for printing 10, 12, 16, 20 pages, for the Herald had suffered a crippling loss, and needed that volunteer advertising desperately. Philadelphia? It seemed fantastic, for Philadelphia was nearly a hundred miles away. To be sure, it had plenty of big newspaper plants, but could we bring our papers back to Baltimore in time to distribute them? The circulation men, consulted, were optimistic. “Give us 50,000 papers at 5 a.m.,” they said, “and we’ll sell them.” So Meekins, at noon or thereabout, set off for Philadelphia, and before dark he was heard from. He had made an arrangement with Barclay H. Warburton, owner of the Philadelphia Evening Telegraph. The Telegraph plant would be ours from 6 p.m., beginning tomorrow, and it was big enough to print any conceivable paper. Meekins was asking the Associated Press to transfer our report from Baltimore to Philadelphia, and the International Typographical Union to let our printers work there. I was to get out one more edition in Washington, and then come to Philadelphia, leaving Callahan in charge of our temporary office in Baltimore. But first I was to see Oscar G. Murray, president of the B & O Railroad, and induce him to give us a special train from Philadelphia to Baltimore, to run every night until further notice.

The B & O’s headquarters building in Baltimore had been burned out like the Herald office, but I soon found Murray* at Camden Station, functioning grandly at a table in a storage warehouse. A bachelor of luxurious and even levantine tastes, he was in those days one of the salient characters of Baltimore, and his lavender-and-white striped automobile was later to become a major sight of the town. When he gave a party for his lady friends at the Stafford Hotel, where he lived and had his being, it had to be covered as cautiously as the judicial orgies described in Chapter XII. He looked, that dreadful afternoon, as if he had just come from his barber, tailor and haberdasher. He was shaved so closely that his round face glowed like a rose, and an actual rose was in the buttonhole of his elegant but not too gaudy checked coat. In three minutes I had stated my problem and come to terms with him. At 2 o’clock, precisely, every morning a train consisting of a locomotive, a baggage car and a coach would be waiting at Chestnut Street Station in Philadelphia, with orders to shove off for Baltimore the instant our Heralds were loaded. It would come through to Camden Station, Baltimore, without stop, and we could have our circulation hustlers waiting for it there.

That was all. When I asked what this train would cost, the magnificent Murray waved me away. “Let us discuss that,” he said, “when we are all back home.” We did discuss it two months later—and the bill turned out to be nothing at all. “We had some fun together,” Murray said, “and we don’t want to spoil it now by talking about money.” That fun consisted, at least in part, of some very exuberant railroading. If we happened to start from Philadelphia a bit late, which was not infrequent as we accumulated circulation, the special train made the trip to Baltimore at hair-raising speed, with the piles of Heralds in the baggage car thrown helter-skelter on the curves, and the passengers in the coach scared half to death. All known records between Philadelphia and Baltimore were broken during the ensuing five weeks. Finally the racing went so far beyond the seemly that the proper authorities gave one of the engineers 10 days lay-off without pay for wild and dangerous malpractice. He spent most of his vacation as the guest of our printers in Philadelphia, and they entertained him handsomely.

But there was still a paper to get out in Washington, and I went there late in the afternoon to tackle the dismal job. The best Bone could do for us, with the Baltimore News cluttering the Post office all day and the Post itself printing endless columns about the fire still raging, was four pages, and of their 32 columns nearly 13 were occupied by the advertisements I have mentioned. I got the business over as soon as possible, and returned to Baltimore eager for a few winks of sleep, for I had not closed my eyes since Sunday morning, and it was now Wednesday. In the Herald’s temporary office I found Isidor Goodman, the night editor. He reported that every bed in downtown Baltimore was occupied two or three deep, and that if we sought to go home there were no trolley-cars or night-hacks to haul us. In the office itself there was a table used as a desk, but Joe Callahan was snoring on it. A dozen other men were on the floor.

Finally, Isidor allowed that he was acquainted with a lady who kept a surreptitious house of assignation in nearby Paca Street, and suggested that business was probably bad with her in view of the competing excitement of the fire, and that she might be able in consequence to give us a bed. But when we plodded to her establishment, which was in a very quiet neighborhood, Isidor, who was as nearly dead as I was, pulled the wrong doorbell, and a bass voice coming out of a nightshirt at a second-story window threatened us with the police if we didn’t make off. We were too tired to resist this outrage, but shuffled down the street, silent and despairing. Presently we came to the Rennert Hotel, and went in hoping to find a couple of vacant spots, however hard, on a billiard table, or the bar, or in chairs in the lobby. Inside, it seemed hopeless, for every chair in sight was occupied, and a dozen men were asleep on the floor. But there was a night clerk on duty whom we knew, and after some mysterious hocus-pocus he whispered to us to follow him, and we trailed along up the stairs to the fourth floor. There he unlocked a door and pointed dramatically to a vacant bed, looking beautifully white, wide and deep. We did not wait to learn how it had come to be so miraculously vacant, but peeled off our coats and collars, kicked off our shoes, stepped out of our pants, and leaped in. Before the night clerk left us we were as dead to this world and its sorrows as Gog and Magog. It was 4 a.m. and we slept until 10. When we got back to the Herald’s quarters we let it be known that we had passed the night in the house of Isidor’s friend in Paca Street, along with two rich society women from Perth Amboy, N.J.

That night we got out our first paper in Philadelphia—a gorgeous thing of 14 pages, with 20 columns of advertising. It would knock the eyes out of the Sun and Evening News, and we rejoiced and flapped our wings accordingly. In particular, we were delighted with the Evening Telegraph’s neat and graceful head-type, and when we got back to Baltimore we imitated it. Barclay Warburton, the owner of the Telegraph, came down to the office to see us through—elegantly invested in a tail coat and a white tie. Despite this unprofessional garb, he turned out to be a smart fellow in the pressroom, and it was largely due to his aid that we made good time. I returned to Baltimore early in the morning on the first of Oscar Murray’s special trains, and got a dreadful bumping on the curves and crossings. The circulation boys fell on our paper with exultant gurgles, and the next night we lifted the press run by 10,000 copies.

We stayed in Philadelphia for five weeks, and gradually came to feel almost at home there—that is, if anybody not born in the town can ever feel at home in Philadelphia. The attitude of the local colleagues at first puzzled us, and then made us snicker in a superior way. Save for Warburton himself, not one of them ever offered us the slightest assistance, or, indeed, even spoke to us. We were printing a daily newspaper 100 miles from base—a feat that remains unparalleled in American journalism, so far as I know, to this day—and it seemed only natural that some of the Philadelphia brethren should drop in on us, if only out of curiosity. But the only one who ever appeared was the managing editor of one of the morning papers, and he came to propose graciously that we save him a few dollars by lending him our halftones of the fire. Inasmuch as we were paying his paper a substantial sum every day for setting ads for us—the

Evening Telegraph composing room could not handle all that crowded in—we replied with a chilly nix, and he retired in a huff.

There was a press club in Philadelphia in those days, and its quarters downtown offered a convenient roosting-place for the hour or two after the night’s work was done. In any other American city we’d have been offered cards on it instantly and automatically, but not in Philadelphia. At the end of a week a telegraph operator working for us got cards for us in some unknown manner, and a few of us began using the place. During the time we did so only one member ever so much as spoke to us, and he was a drunken Englishman whose conversation consisted entirely of encomiums of Barclay Warburton. Whenever he saw us he would approach amiably and begin chanting “Good ol’ Bahclay! Good ol’ Bahclay! Bahclay’s a good sawt,” with sawt rhyming with caught, and apparently meaning sort. We agreed heartily, but suffered under the iteration, and presently we forsook the place for the saloon patronized by the Herald printers, where there was the refined entertainment described in Chapter XI.

Meekins’s arrangements for getting out the Herald so far from home were made with skill and worked perfectly. Callahan remained in Baltimore in charge of our field quarters outside the burned area, and on every train bound for Philadelphia during the afternoon he had an office boy with such copy as had accumulated. At 6 o’clock, when the Evening Telegraph men cleared out of their office, we opened a couple of private wires, and they kept us supplied with later matter. Even after the fire burned out at last Baltimore was in an appalling state, and there were plenty of old Baltimoreans who wagged their heads despairingly and predicted that it would never be rebuilt. One such pessimist was the Mayor* of the town: A little while later, yielding to his vapors, he committed suicide. But there were optimists enough to offset these glooms, and before we left Philadelphia the debris was being cleared away, many ancient and narrow streets were being widened, and scores of new buildings were started. All these debates and doings made for juicy news, and the men of the local staff, ably bossed by Callahan, poured it out daily. Meekins would come to Philadelphia two or three times a week to look over his faculty in exile, and I would drop down to Baltimore about as often to aid and encourage Joe. We had our own printers in Philadelphia and our own pressmen. Our circulation department performed marvels, and the advertising department gobbled up all the advertising in sight, which, as I have said, was plenty. The Herald had been on short commons for some time before the fire, but during the two or three months afterward it rolled in money.

Once I had caught up on lost sleep I prepared to do a narrative of the fire as I had seen it, with whatever help I could get from the other Herald men, but the project got itself postponed so often that I finally abandoned it, and to this day no connected story has ever been printed. The truth is that, while I was soon getting sleep enough, at least for a youngster of 24, I had been depleted by the first cruel week more than I thought, and it was months before I returned to anything properly describable as normalcy. So with the rest of the staff, young and old. Surveying them when the hubbub was over, I found confirmation for my distrust, mentioned in Chapter XI, of alcohol as a fuel for literary endeavor. They divided themselves sharply into three classes. Those who had kept off the stuff until work was done and it was time to relax—there were, of course, no all-out teetotalers in the outfit—needed only brief holidays to be substantially as good as new. Those who had drunk during working hours, though in moderation, showed a considerable fraying, and some of them had spells of sickness. Those who had boozed in the classical manner were useless before the end of the second week, and three of them were floored by serious illnesses, one of which ended, months later, in complete physical and mental collapse. I pass on this record for what it is worth.

[1] Bone was an Indianan, and had a long and honorable career in journalism, stretching from 1881 to 1918. In 1919 he became publicity chief of the Republican National Committee, and in 1921 he was appointed governor of Alaska. He died in 1936.

[2] Perhaps I should explain some printers’ terms here. The stones are flat tables (once of actual stone, but now usually of steel) on which printers do much of their work. Type is kept in wooden cases divided into boxes, one for a character. As it is set up by the compositor it is placed in galleys, which are brass frames, and then the galleys are taken to the stone and there made up. Sometimes, after the printing has been done, the type is returned to a stone, and left there until a convenient time to return it to the cases. To pick sorts is to go to such standing type and pick out characters that are exhausted in the cases. Pied type is type in such confusion that it cannot be returned to the cases by the usual method of following the words, but must be identified letter by letter. To forget the case, mentioned below, is to lose the art of picking up types from the boxes without looking at them. The boxes are not arranged alphabetically, and a printer learns the case as one learns the typewriter keyboard.

From “Days Revisited: Unpublished Commentary”

We had a story: The story, in fact, was big enough to bring in a swarm of reporters from other cities, and for 10 days it fought with the Russian-Japanese War, which had begun at almost precisely the same moment, for space on the first pages of the newspapers. One of the reporters from New York was Herbert Bayard Swope, then of the Herald. I believe that this was my first meeting with him; later on I came to know him well and when he was married in Baltimore in 1912 I was best man at the wedding. After “Fire Alarm” appeared in the New Yorker, on July 6, 1941, I received a number of letters from old timers who had covered the fire.

Meekins had only $5: Meekins’s son, Lynn W., wrote to me on February 7, 1942:

That he had as much as $5 on the night of February 7, 1904, was, and is, news.

It was certainly not common, in those days, for journalists to carry any considerable amount of cash in their jeans. For one thing, they seldom had it, and for another thing they all believed that having it would set up a temptation to spend it. But I dissented, and always went armed with at least $25. Maybe that was because I was beginning to pick up an appreciable income outside the office, and thus felt rich. The new copy-reader here mentioned was C.C. Foss, a cherubic little fellow who was also a Methodist preacher. He was the office encyclopedia, and in recognition of his learning the boys gave him the nickname of the Reverend Professor Doctor. Foss occasionally supplied pulpits in Baltimore and its suburbs, to the derision of the Herald agnostics. For this service he arrayed himself in an old-fashioned frock coat with long skirts. He was not noticeably pious on weekdays, and now and then he joined the boys of a Saturday night on what they called a sentimental journey, i.e., a roving expedition through the downtown saloons, usually ending in a bawdy-house. He excused these unclerical doings by declaring that he was a student of sociology, and eager to investigate the life of the depressed classes.

Percy Heath, a merry fellow, specialized in leading the Reverend Professor Doctor astray and had a lot of fun with him. Once, when he was known to be booked for a sermon at a Methodist church on Sunday morning, Percy steered him on Saturday night to Schild’s wine room in Holliday Street near Baltimore, and there filled him with so much California Rhine wine at five cents a glass that when he got into the pulpit the next day he was barely able to read his text. Another time, also on a Saturday night before a sermon day, Percy locked him in a room at Blanche Forbes’s house of call in Watson Street with a deaf-and-dumb girl, and there he remained all night, occasionally beating on the door but afraid to make too much noise, lest the cops rush in and his infamy be exposed. Blanche was in on the joke. She reported later that he had been liberated at last at 5 a.m. Cross-examined on Monday by Percy, Foss said that he had learned a lot about the life of the poor from the deaf-and-dumb girl and had thus been enabled to preach a very powerful sermon. After a year or so on the Herald he vanished, and I don’t know what became of him.

The magnificent Murray: Murray has been forgotten in Baltimore, but deserves to be remembered. He kept a sort of harem at the Stafford, then a fashionable place, and it was considered fair sport for the young bucks of the town to use his girls. Born in Connecticut in 1847, he had a long railroad career before coming to the B & O in 1896. He died on March 14, 1917.

The Mayor: The mayor who committed suicide was Robert M. McLane. This was on May 30, 1904, nearly four months after the fire. It is the official legend in Baltimore, as I say in the text, that fears for the future of Baltimore induced him to take his life, but I have always had doubts of it. For the Baltimore papers his suicide was a story only less grand and gaudy than that of the fire itself, and for days the staffs of all of them sweated over the job of finding his true motive.

The most plausible of the tales that came in to the Herald, though we could not print it, was unearthed by a woman reporter named Edith M. Walbridge. She got it from women friends of the McLane family and it was to the following effect: McLane, only a little while before, had married a young widow—and made the disconcerting discovery that he was virtually impotent. On the day of his death he returned from the City Hall early in the afternoon and found his wife in the house. One thing led to another, and they were presently on a couch in his library. When, after he had brought her to a high state of incandescence, his manly powers again failed him, he rushed to a cupboard, took out a pistol (or maybe it was a gun), and shot himself in her presence. The poor woman was in a state of hysteria for days, but her friends wormed the story out of her, and one of them blabbed to La Walbridge. There was, in fact, no more uneasiness about the future of Baltimore at the time he killed himself. The town, after refusing all assistance from outside the bounds of Maryland, had proceeded energetically to the work of clearing off the debris of the fire, and plans to widen the streets of the burned district and otherwise improve it were already under way.

From H.L. Mencken: The Days Trilogy, Expanded Edition, edited by Marion Elizabeth Rodgers and published by The Library of America.

Excerpt from Newspaper Days by H.L. Mencken, published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC. Copyright © 1940, 1941 by Alfred A. Knopf. Copyright renewed 1969 by August Mencken and Mercantile Safe Deposit & Trust Co.

Excerpt from “Days Revisited: Unpublished Commentary” by H.L. Mencken, published with the permission of the Enoch Pratt Free Library. All rights reserved.