It will take many of us a long time to wrap our heads around the loss of Robin Williams. I’ve talked about him with friends and co-workers the past few days, and watched a ton of YouTube, where you can find some of Williams’s finest talk show appearances and a good serving of his stand-up comedy. I’d like to point you in the direction of the 1992 Playboy Interview with Larry Grobel; the outstanding—essential, really—podcast interview with Marc Maron, and sympathetic remembrances by Peter Coyote, Russell Brand, and Andrew Solomon. Over at The Stacks, I excerpted a series of reviews by Pauline Kael, an early admirer of his movie acting.

Now, I’m honored to present Joe Morgenstern’s 1990 profile of Williams. Morgenstern, the winner of the 2005 Pulitzer for criticism, was a longtime movie critic for Newsweek. Since 1995, he’s graced the pages of The Wall Street Journal. He’s also written longer pieces for Rolling Stone, Esquire and the New Yorker. I was a freshman in college when his story on Williams, “More than a Shtick Figure,” appeared in the November 11, 1990 edition of the New York Times Magazine. I thought it was terrific then and it more than holds up. Joe was gracious enough to give his permission to let us reprint it here. And so, in the spirit of hanging on to Williams just a little bit longer, please enjoy. –Alex Belth

* * *

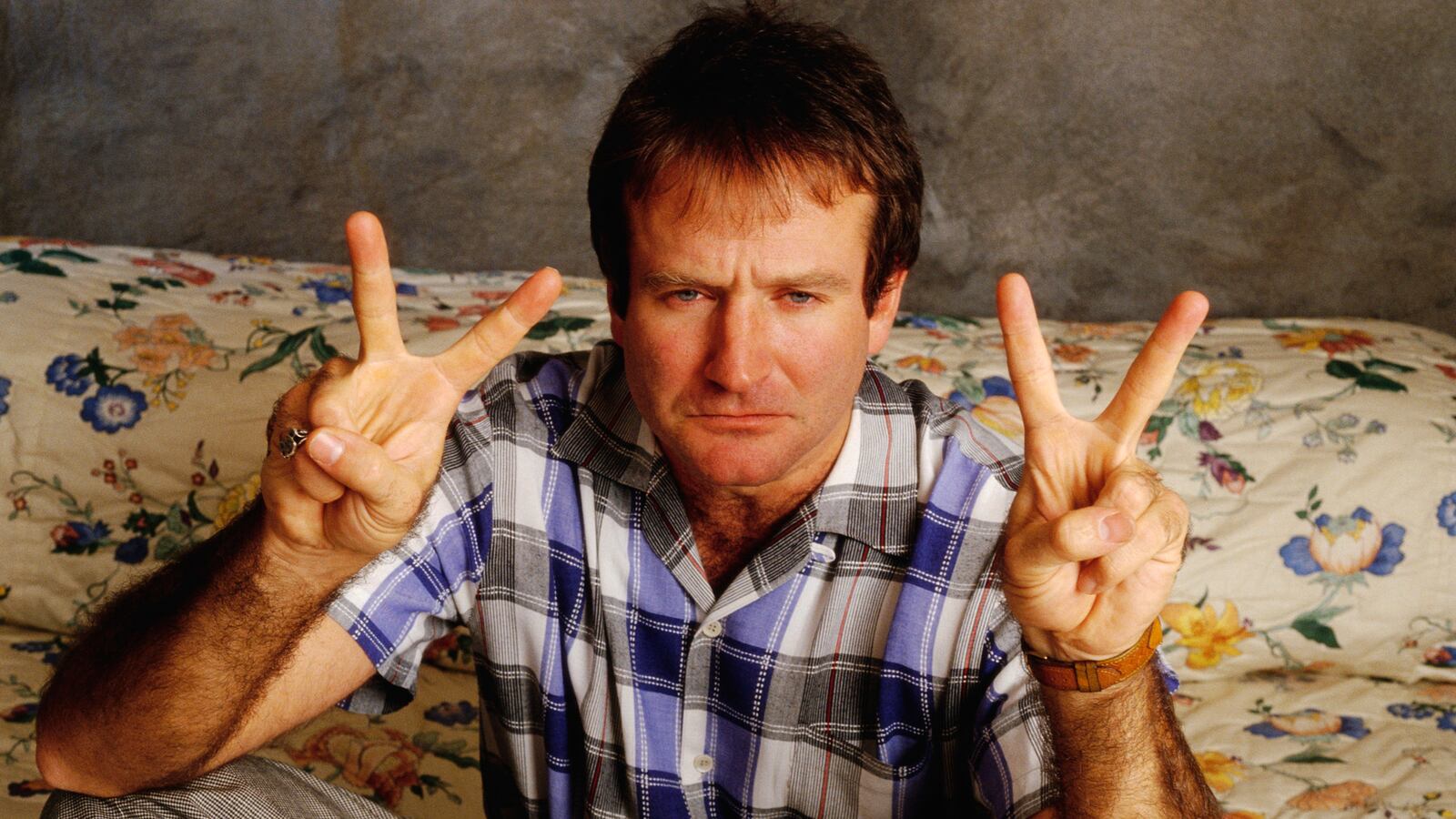

On a movie set, Robin Williams wears two heads. When the camera rolls, he is an actor of great authority and accomplishment. Between takes, he is himself, or a stand-up version of himself, giving little performances for his fellow performers. These cameos, at the very least, are endearingly silly—the sound of his mind at idle—and occasionally so startling that his peers wonder, as audiences have been wondering for more than a decade, if he’s working off his left brain, his right brain, or instructions from outer space.

For a sense of how quick he can be, there’s a remark he tossed off on the set of Awakenings, a new movie drama based on a book of medical case studies by the neurologist Oliver Sacks. Awakenings, which opens next month, co-stars Robert De Niro as a patient who, by the late 1960’s, when the action takes place, has spent three decades in a coma; Williams is the doctor—modeled on the intense, idiosyncratic Sacks—who brings him back to life. One gray afternoon last winter, toward the end of a long, grueling stretch of location filming at an old psychiatric facility in Brooklyn, the director, Penny Marshall, felt as drained as the cast and crew.

“It’s so hard shooting in a mental hospital,” she said, except that the phrase, slurred by fatigue, came out as “menstrual hospital.”

“Yes, and shooting a period picture,” Williams chimed in brightly, no pause to ponder the play on words, no more than nanoseconds between her slip and his lip.

Then there’s his behavior one morning several weeks ago at the Columbia Pictures lot in Culver City, Calif., on a tiny, crowded set representing a video shop. The movie was The Fisher King, in which Williams plays a homeless man who once was a professor of medieval history and is now charismatically mad; the cast includes Jeff Bridges and Amanda Plummer. In the scene being shot, Williams’s character, Parry, first meets Plummer’s Lydia, an ugly duckling whom he has idealized at a distance as his inamorata. Between takes, Williams played to the other actors or to the director, Terry Gilliam.

He didn’t do anything startling this time, just snippets from his stand-up scrapbook: a little Jesse Helms, some Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker, a bit of Gandhi (in a singles bar).

Yet his clowning had a calming effect on everyone, including himself, for the scene was tricky to shoot and, at the point when Parry and Lydia look into each other’s eyes, heart-stoppingly delicate to play. During one break in the filming, he was a fatuous British director, “exploring the essence of what we call cinema!” During another, he was a bubbly Broadway choreographer: “All right, people, let’s keep that energy up!” Through it all, he kept switching, with eerie virtuosity, between the silliness of a court jester and the stillness of an actor, a superb actor who has won back-to-back Oscar nominations in the past two years—for Good Morning, Vietnam and Dead Poets Society—and who is becoming a genuine star.

The jester first came to prominence in the 1970’s, with stand-up appearances that were legendary for their perfervid pace and wild, associative leaps; it was Williams’s comedy work that led to his sensational television debut as Mork, the ardent, naïve extraterrestrial of Mork and Mindy. But watching him in a club or a concert could also be scary. The jester’s improvisational method seemed tinged with madness. (Williams now speaks openly of the drugs and alcohol he once abused, and uses no more.)

Since then, his act has grown much sharper and less frenetic, though the free associations, the intuitive leaps can still leave audiences breathless. When writers describe his comedy, they usually fall back on such metaphors as synaptic storms, jazz riffs and computers, though computers are stumblebums when it comes to intuitive leaps. In an introduction to her television interview with him last year, Barbara Walters said: “You can’t help wondering how his mind works, how he got this way.” It was the right question, even though the phrasing suggested an affliction instead of a blessing, and the show didn’t come up with any answers.

Do answers exist? “I wouldn’t have known how to talk about the process a few years ago,” Williams told me. “I would have said I don’t know what happens, it just happens.”

These days, though, he’s more reflective, with lots of good fortune to reflect on: his soaring career in feature films, a happy second marriage and a 15-month-old daughter named Zelda. (He has a 7-year-old son, Zachary, by his first marriage.) Toward the end of shooting on The Fisher King, he spent hours—first at his rented Malibu beach house and later at his bay-front San Francisco home—in a calm, earnest exploration of how the process works. He also demonstrated it, with unquenchable glee.

A conversation with Robin Williams can stay calm for a long time. He loves to play with abstract ideas, and he’s a good listener. Sometimes he’s so good that you get the impression of an emotional mirror. If you’re calm, he’s calm; if you’re up, he’s up—way up. A conversation can also turn suddenly into a séance, as a host of characters pop out of his mouth: Chico Marx, Henry VIII, Sylvester Stallone, or Albert Einstein, plus nameless but vivid Nazis, Southern belles, redneck hunters, Jewish mothers, ghetto blacks, and tight-jawed WASPs. Here’s Williams as Chico, critiquing a Picasso:

Hey, thatsa no good! Where’s the rest of the lady? She’sa gotta no breasts!

Yet the metaphor of a spirit medium is as misleading as that of a computer. It’s not that other characters speak through him, but that he speaks, thinks and improvises through other characters.

Take the business with Chico, which came into being one night the way much of Williams’s material is born, while he was fooling around in front of friends. He began, he recalls, by setting forth a cockeyed premise: the Marx brothers selling modern art. That suggested the invincibly uncultivated Chico; his impression got a quick laugh—laughter is always the fuel, Williams says—and he was off and running:

Hey, thata Henry Moore, he’sa gotta no stomach. That Botero, thatsa terrible, thata lady’s too fat, she look like a Michelin woman! Hey, I say get me a dolly and whaddya bring me back? Thatsa watch melting on a tree! l say get me a mirror, you get me a Miró. I looka in that and I don’t see me, l see a red dot!

Williams likens this to ventriloquism without a dummy. The analogy is an intricate one, since it means he plays tricks on himself, as well as on the audience. By using an alter ego, he liberates himself, relaxes himself so he can invent freely. In a sense, he absolves himself of responsibility for inventing new material on his own; it’s the other guy, the compulsively gabby character, who triggers the specific ideas.

“First you’re aware that you’re doing this impression—Hey, thatsa no good—and all of a sudden you’re aware of making this guy talk about something very esoteric, making him make references, and then you wonder, ‘Where did that Botero reference come from?’”

Finding comedy through character is only part of what Robin Williams does. Another part is a pell-mell process of associative thinking, a process so playful, fluid and free that he can make that instant connection, say, between a menstrual hospital and a period picture.

But character is central, indeed essential, to what he does, and to the way he thinks. For another example, we are sitting in his living room in San Francisco discussing Oliver Sacks, the author of Awakenings (and also of the recent best seller The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat). Williams speaks with great feeling of how lonely the British-born neurologist must have been as a brilliant child in English private schools. Yes, I say, and a Jewish child in the bargain. Instantly Williams is off and running again, in the character of an unctuously anti-Semitic English headmaster:

We’re so happy to have you and all that, but Gawd, I’m sorry we don’t have any of your food heah. What is it that you people actually eat? And will you be doing any of your rituals while you’re heah? Some of us would like to come watch if you do any sacrifices or anything like that. Gawd … we know you’re a traveling people. Did you bring any of your … your accoutrements? Any of your tents or anything? Just kidding. Just kidding. Teddy, oh Teddy, do come downstairs, a young Jewish boy’s come to see us.

Such seemingly effortless—and mordant—improvisation can be a marvel to behold. It could also be hopelessly intimidating to behold, were it not for Williams’s candor about how hard he actually works, and how often instant inspiration eludes him. He talks of the fear that can still paralyze him for brief moments on stage, and of the willpower needed to keep that fear under control when new ideas are slow to come. “It’s like those old war movies,” he says, plunging into another British character, a colonial officer in some Crimea of standup comedy:

Hold your fire … don’t do that easy premise! Don’t grab your genitals! Try to find it, boy! You can do it! There’s the idea! There’s something new! Good fellow. you’ve found it!

When Robin Williams, who is 39 years old, first discovered improvisational comedy as a young man in San Francisco in the early 1970’s, he believed, as most people do, that whole routines were invented on the spot: “I used to go watch the Committee”—a ground-breaking improvisational troupe—“and always thought, ‘Oh, God, that’s so brilliant.’ I didn’t realize some of it was scripted and they may have been doing that scene for the past three years.”

This is not to say that the best sleight-of-mind wizards don’t pluck some topical inventions from thin air. Williams did it with me several times, for instance when I mentioned the Hubble Space Telescope. Had he seen an article in that morning’s paper about the possibility of fitting the orbiting instrument with a corrective lens? He hadn’t, but that didn’t keep him from immediately thinking aloud about a cosmic eye chart, then becoming the telescope itself as it squinted to read:

Alpha. Alpha Centauri, that’s all I can see—then a sudden switch to a voice he uses frequently, that of HAL, the wounded, one-eyed computer in 2001—send up comfort drops. Dave, it hurts, I have to take the lens out.

A skeptic might wonder if he really had seen the story in that morning’s paper and was passing off flash-frozen goods for fresh. But apart from the unlikelihood of such a tactic—guile isn’t one of Williams’s gifts—it’s beside the point. Pure invention is the exception rather than the rule in improvisational comedy, which has always been a patchwork of old and new (not to mention blue—Williams has his own arsenal of penis jokes). Part of the fun comes from the invisible weaving.

Nevertheless, the greatest pleasure for the performer, the payoff for all the angst and perspiration, comes from making discoveries while the audience is watching. For Williams, it’s like a runner’s high: “That’s why going on stage is so exhilarating for me. When you find that new idea, when you come up with a concept and find that it works, it’s the creation of the moment that’s so incredible.

“And you know, they’ve discovered there actually is a slight endorphin release during creative moments. It’s like, Bing!, this is part of evolution. Eventually the brain figured out”—he assumes a deep, slightly robotized voice—“If you create, we’ll reinforce you. This and sex. You can see why Einstein always looked like”—he finishes the thought as a blissed-out German—“Ah, it was good for me.”

I laugh, of course, and he’s glad to have the laughter, as always. “That means creation is a drug! It is a drug, and it was designed that way, evolution-wise, to make that Bing!” But he’s also profoundly serious about this passion for discovering new ideas, which explains why he still loves to work out, often unannounced, in comedy clubs. It may also explain why he’s been confessing, for more than a decade, that his greatest problem in stand-up is getting off stage.

“Free at last, free at last! A head does not need a body to survive!” chortles Robin Williams as the disembodied King of the Moon in Terry Gilliam’s previous picture, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. It’s a vivid comic turn (and an uncredited one) that few have seen, since the movie was a fascinating mess that never found an audience: the King’s Italianate head, with its powdered wig and powdered face, lives a life of the mind quite apart from his body, which carries on like a bloated, brainless satyr. Williams’s own body is in great shape. A track star in school, he continues to run regularly and to work out in a gym. All the same, it’s his head that has freed him to explore topical comedy, and this sets him apart from the other comic genius of his generation, Richard Pryor, a man who reached heights of brilliance by plumbing the depths of rage and pain in his own heart.

To be sure, the contrast can be overdrawn: can be overdrawn. Pryor wouldn't have succeeded without his superb intelligence, Williams wouldn't have succeeded without his abiding passion. Yet there’s a world of difference between these two men, and the subject of Pryor prompts Williams to praise his colleague lavishly, while offering a cautious, conflicted appraisal of himself:

“He has this incredible ability to recognize the most basic human truths, to talk about deep-seated fears. I’ve never been able to talk personally about things, some of the negative things that obviously happened in my life. Some day I will. I’ll be able to talk about them and make them funny, or at least get them out. But that’s such a Pandora’s box. Once you open it, can you deal with it? With your insecurities and your pains? Of course, it isn’t that there’s a lot of pain. I was an only child who grew up in an upper-middle-class neighborhood. The joke is, I played with myself and that was it.”

In the portrait that’s usually drawn of Robin Williams’s family, the most conspicuous element is the gilded frame. His father, Robert, who died three years ago, was a Ford Motor Company executive. Robin was an excellent student, as well as a fine athlete. He was also shy and lonely as a boy; his mother, Laurie, who had done some acting as a young woman in New Orleans, often worked as a fashion model.

Williams’s first performance came at the age of about 12, when he started entertaining his mother with imitations and little routines. Laurie Williams was a great audience. More than that, she was a comic in her own right. “She was always funny,” her son says. “She had the jokes and the poems, all the things that people have been seeing her do on talk shows.”

A conversation with his mother, who lives in suburban San Francisco, dispels any doubt about where Robin Williams got his energy and sense of fun. She talks of her love of taking chances, her belief that “man was put on earth to know great joy.” She reminisces about an invitational dance at the Lake Forest-Lake Bluff (Ill.) Bath and Tennis Club, where she arrived in an elegant dress but with her two front teeth obscured by Black Jack gum: “All the women were going, ‘You”d think someone who could afford clothes like that could afford to get her teeth fixed.’”

And what of his father? At first, Robin recalls him in terms that suggest how remote Robert Williams must have seemed: elegant, ethical, quiet. Laurie Williams uses distanced descriptions, too. “His father was strict and stern, but very fair, and Robin adored him.” Later, she adds that her husband’s nickname at home was Lord Stokesbury, Viceroy of India: “He was not for children cutting up.”

Yet there was another side to this cool, handsome patrician, and it set him apart from his fellow executives in the Motor City. Robert Williams had been born to wealth, but his family’s fortune, based on strip mines and lumber interests, was squandered to the point that he was forced to work in the strip mines himself. Though he made it back to the top by dint of talent and hard work, he remained a deep-dyed cynic for the rest of his life. “He was this wonderful, elegant man who thought the world was going to hell in a hand basket.” Williams says. “It was basically, ‘You can’t trust them. Watch out for them. They’ll nail ya. Everybody’s out to nail ya.’”

So a rich kid Robin was, but one who grew up with intimations or an alternate reality lurking behind the fancy façade; maybe that’s why his best comedy routines, like the one about Christianity starting out as a mom and pop religion—“Mom was a virgin and Pop was God”—are those that work electrifying variations on the blandness or everyday life. Whatever the connections, Williams feels he’s just beginning to understand them, and to see his father clearly as a man.

“I realize what he gave me is what’s been working now in some of these dramatic movies,” he says. “He had a great stillness and a power to him, a great kind of … I can only use the word depth. He knew exactly what and where he’d been, who he was and why he did certain things. He was never pushed along. If things weren’t done the way he felt was right, he left. That’s coming into play now when I do movies like Dead Poets Society, and I find myself thinkIng, ‘That’s for you, Pop.’”

As Robin Williams’s movie performances grow deeper and more complex, it’s tempting to think of him as a comic prodigy who somehow taught himself to play other people. In reality, he’d been a trained actor well before hitting it big in comedy clubs: three years’ study on a scholarship at Juilliard, where the rigorous curriculum includes voice, movement, and character, from the theater’s roots in ancient Greece to the present day. Those roots enriched his stand-up work, just as his comic instincts and his genius for improvisation eventually made him a better actor. But he hasn’t found it easy to get his jester head and his actor head together.

“Stand-up is aggressive,” he says. “Attack! Get the laugh! People always talk about it as a defense mechanism, and it’s usually true. You’re trying to keep the world out by being aggressively funny, or by mocking it, because somewhere along the line, when you let it in, it hurt. In acting, though, you have to take that chance, you’ve got to let things in. Because a lot of it is about being hurt, or being joyous, but letting emotions come in and affect you.”

Ten years ago, when Williams first moved from Mork and Mindy into feature films, Hollywood saw him as a wild man whose wildness could never be harnessed in the service of other characters. That was hardly the problem, though, in his first movie, Popeye, a failed fantasy that let him display his gift for mimicry and little more, Williams, who did a perfect imitation of Popeye’s metallic cartoon voice, seemed sandbagged by a witless script and elaborate prosthetics: the squinting eye, the bulging plastic forearms. And some genuine wildness might have helped The World According to Garp, an erratic castration fantasy in which he was forced to play second banana to a passel of predatory women.

In another flop called The Survivors, he gave a brave performance as a gun-crazed executive, but it was too much of a good thing in such a rickety vehicle. What he needed was challenging material and a director who could help him focus his unique vitality without losing it. The first time he found both was as a Russian jazz saxophonist who emigrates to New York in Moscow on the Hudson, the exuberant topical comedy directed by Paul Mazursky.

“At the time I first knew Robin, he was very manic,” recalls Mazursky, who used to be a stand-up comic himself. “We went to several comedy clubs together, and actually once I agreed to go on stage with him, but he was so funny I ran. On the set, I always felt what I had to work at was getting the tension out, and I think we did it, even though we had a couple of shouting matches at the beginning where I’d say, ‘It’s too much!’ and he’d say, ‘It’s not anything.’ I like the man very much. He’s very sweet, and he’s obviously somebody who wants to keep growing. He has a desperate need to be wonderful.”

Williams’s first box office hit, Good Morning, Vietnam, made room for his manic energy by allowing him to improvise whole scenes in the character of Adrian Cronauer, the anti-establishment, motor-mouthed military disk jockey. But those improvised riffs, as presented on screen, rarely built beyond mania and funny voices, while the scripted scenes exploited Williams’s own sweetness by sanctifying his character. Cronauer came off as a high IQ God’s fool.

Not until last year was Robin Williams able to integrate his various gifts in a feature film, the hugely popular Dead Poets Society. For all its obvious contrivances, Dead Poets dramatized human concerns rarely addressed by Hollywood—love for learning, passion for living—and it is almost impossible to imagine the movie without Williams’s performance as John Keating, the renegade English teacher in a tradition-bound boarding school. He brought the stillness and the depth that he had found in his father, but he also mixed in his own nimble intelligence, a smidgen of shtick—impressions of Brando and of John Wayne as Macbeth—and a beautifully modulated version of the passion that we had first seen, without quite knowing what to make of it, in the young Mork.

If the life of the mind enriched Dead Poets Society, it dominates Awakenings, in which Williams plays a neurologist who uses the drug L-dopa to free another intelligence that’s been trapped in a body turned to stone by disease. When Williams talks about the character he plays, he sounds as if he’s describing an extravagant fictional creation, a sort of shy, more cerebral Falstaff. Yet Oliver Sacks isn’t fictional at all, even if a few of the facts of his life border on the bizarre.

“To play him was an amazing combination of things,” Williams says. “He’s Schweitzer and Schwarzenegger, a gentle man who used to squat-press 600 pounds. He’s incredibly shy, but aggressive in how he pursues an idea. He’s got this amazing mind, but sometimes he can barely speak. He has his own microclimate that he needs to function perfectly—60 degrees, sometimes 70, but if it goes beyond that he overheats, like a penguin. So you see him sitting there watching the dailies, a big guy on tiny little stool with a giant ice bag on his head that says ‘Author,’ and you go, ‘O.K., that’s it, good night, everybody, so much for art imitating life.’”

That’s an arresting description of a man, but it’s also a description of an acting challenge. During the first three weeks of rehearsal, art imitated life fairly literally. “I was playing him full out, complete with the accent and mannerisms,” Williams says. Then the director, Penny Marshall, encouraged him to drop some of the literal behavior and put more of himself into the character. A decision was also made to change the character’s name from Sacks to Sayer, a small matter, but a liberating one. “It freed both him and me simultaneously, relaxed a certain standoff,” Williams says, “because Oliver had been coming to the set all the time to help us, and for him it was like walking into a three-dimensional mirror.”

Sacks discusses this surreal experience with great humor, but he makes no bones about his misgivings. “I was a little scared when I learned that someone with such powers of apprehension as Robin was getting me as a subject,” Sacks recalls. “Because he does have this extraordinary, at times involuntary, power of mimicry. No, mimicry is the wrong word. He just sort of takes in the entire repertoire of a person: their voice, gestures, movements, idiosyncrasies, habits. He gets you.”

The subject’s misgivings grew as Williams worked on the exterior aspects of his character. “It was like a twin,” Sacks says, “like encountering someone with the same impulses as one’s own. I’d see his hand on his head in a strange way, then I’d realize that was my hand. But I hasten to add that this was an early and transient stage, a mirroring that gave way to much deeper and richer and unexpected development.”

Sacks insists that he learned less about Williams than Williams learned about him: “It’s in the nature of things that the subject does not get to know his portrayer.” Before production began, however, the two men spent long hours together visiting Sacks’s patients, and the doctor’s observations of the actor are acute:

“At first, I couldn’t always tell his feelings to me, but I saw his feelings to the patients, who sort of glowed under his curiosity, and his sense of fun, and his inability to posture. He met one patient, a man named Shane, who has Tourette’s syndrome, and he and Shane were instant brothers. Robin would sometimes say of Shane that Shane made him feel more alive, that Shane was life itself. But I think exactly the same is true of Robin.

“I don’t mean to suggest that he has Tourette’s. Clearly he doesn’t. But just as clearly, there’s some part of him which is unconscious and preconscious, with an extraordinary rapidity and explosiveness. It suddenly comes out. It has a mind of its own. It is and isn’t under control. The ‘it’ I’m talking about is a form of genius, of course, and this rush up from the depths is characteristic of genius. What sometimes comes up out of Robin is planetary, volcanic—it’s the geology of the human psyche. This hot stuff from the center or his psyche suddenly comes through.”

On the face of it, Sacks is describing a different person from the thoughtful, often quiet man I met in California. But volcanoes needn’t erupt constantly to maintain their active status. What seems to have come over Robin Williams is a recent and nourishing calm, at least off stage; indeed, a belief that such a place as offstage exists. The two most obvious reasons for this change are his marriage last year to his second wife, Marsha, who is a painter and sculptor with an academic background in fine arts, and their daughter, Zelda, who has not only mastered stand-up but is starting to walk.

“When he’s at home,” Marsha says, “he relaxes, he reads, he absorbs. He shuts down that performing part of himself, though of course it comes back in flashes. And he’s finally able to extend the relaxation to friends and others he meets, so he can carry on more ordinary sit down conversations. There are times now when he can relax enough to know he’s loved even when he’s not being funny.”

Yet onstage exists as ever, and for all the newfound happiness in Robin Williams’s private life, as well as the growing rewards of his film career, he continues to need the laughs and ecstatic adventure of stand-up. What’s more, he’s an unreconstructed child of the 60’s; his concern about political issues and social causes remains intense. “You gotta keep pushing,” he says, “you gotta keep hitting people out there, they’re all so lulled. When you realize the things that have been happening in the last few years, just legislation-wise, then you have to say, ‘Excuse me, but I think they’re rewriting the Constitution and putting it on an Etch A Sketch, and unless you wake up very soon. It’ll be gone.’”

A balmy summer Thursday in Malibu. After a day off from shooting The Fisher King, Robin Williams decides to work out. In the evening, he drives down the Pacific Coast Highway and into West Los Angeles, arriving at a comedy club at about 9:30. His appearance has already been arranged with the management and with his friend Bob Goldthwait, the comic who’s now on stage, but to the audience it will be a surprise.

Goldthwait is really cooking. In his familiar persona of Bobcat, the frantic slob, he works his way through a succession of topical jokes—rock-and-roll lyrics, censorship at the National Endowment for the Arts, David Duke and Louisiana politics. Waiting in the wings, Williams hears several subjects he’d hoped to fool around with himself, and strikes them from his mental list. As Goldthwait starts to wind down, Williams feels lightheaded and weary; it’s almost like oxygen debt, and he yawns. He often feels this way for a few moments before going on, and he knows what’s behind it—plain old fear. Soon Goldthwait gets off, an unseen voice announces Robin Williams, and he bounds out to the center of the small stage, greeting an audience that greets him as if it had just won the grand prize in the lottery. Suddenly, almost magically, his mind is calm and clear, with oxygen to burn.

He plunges into a subject from the current week’s news: the opening of the Nixon library. “Welcome to the amnesiac wing,” he begins, in the voice of a tour guide. “Now, if you’ll walk through this giant sphincter….” For a while he mines a topical vein: Imelda Marcos, the S&L crisis, AIDS. The audience doesn’t care if this material sounds slightly familiar after Goldthwait’s gloss of current events. Williams senses it, though, and jumps quickly from AIDS to a terrific semi-pantomime bit in which he’s a lover trying frantically to open a foil-packed condom with one hand and his teeth, while keeping his partner aroused with the other hand.

Now the jester has been joined by the actor. In a 30-second history of evolution, he’s the first fish out of water, getting high on a hit of air. Now he’s a precocious simian: Wow, I’m erect! This is followed by a clumsy transition—the clumsiness of which Williams acknowledges—to several ordinary gags about Elvis Presley as the new Christ. He needs a quick recovery, and he makes one by working his way into a reliable routine, the one on Christianity as a mom-and-pop religion. For another few minutes he hums along at cruising speed, delivering lines that he’s been refining for months, but making them sound like spontaneous combustion.

By this time he’s been on stage for more than half an hour, and it seems he can do no wrong as he plays Jesus, various popes, and a raffish Henry VIII. But a few minutes after that, when he asks the audience for a new subject to improvise on, someone who’s either sloshed or has been outside for a smoke shouts “Jesus” and stops Williams in his tracks. “I thought we did that,” he replies. Someone else suggests the Republican Senator Pete Wilson, who is running for governor of California. Williams comes up dry on Pete Wilson, though he makes a stab at doing Pete Rose.

Has the moment come to get off? “This is one or those nights,” he tells the audience, “where you finish the evening in a pool of your own sweat and go ‘What have I been talking about?’” But the evening isn’t over by a long shot. He means what he has said about doing this to practice and to learn, so he keeps searching, searching for new ideas, though he can’t quite find them. Some of the most affecting moments now are the most tentative, as this celebrated comic stumbles as gamely as his toddler daughter. “Once again, too far,” he confesses to the crowd. “Could’ve gotten off, but Mr. Ego said no.”

Then he notices a pretty young woman who’s sitting in front or him and looking sad.

“Don’t look sad,” he tells her.

“She’s a lawyer,” her male companion answers.

Whether this is a non sequitur or some abstruse truth, it’s all Williams needs to ignite and launch. Suddenly he’s into … lawyer jokes! Subpoena envy! Comedy on trial! He’s all over the place, a whirling dervish of an attorney pleading his case. He’s in comedy court, his own skewed version of night court. He’s in comedy heaven, putting himself on trial. “I’m talking to you!” he tells the young lawyer with blazing ardor. “I want to make a confession! Yes, I did it!” And what follows, if truth be told, is another few minutes of amiable anticlimax, after which he stops, says thank you, waves good night, gets a heartfelt standing ovation and finally, reluctantly, makes it off stage.