Gaza City, Gaza—

Is the two state solution dead? I don’t think so, but the conversation is being radically transformed into one that no longer accepts the binary “two states or bust” paradigm and begins to imagine—or live—alternatives.

I spoke to young people, officials and activists in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza over the last two weeks. I was surprised at what I heard.

A large chunk of the Gaza economy comes from international donations, money from UNHRW and other multilateral organizations. A pretty young blogger in Gaza City, Jehan Al Farr, told me that these governmental programs for job creation are “nothing but machines that pull people in and suck out their creativity and motivation.” True entrepreneurship, she says, occurs outside the box, not inside a donor-welfare society. I told her she sounded like a member of the Tea Party. Having spent a year at a Colorado high school (she speaks perfect English), she knew exactly what I meant. She laughed and told me that she is fed up with politics (she is 25) and believes she and her generation can only end the occupation when they stop caring about it and instead, try to go about a normal life of book clubs and social events. “No more death, no more blood. Just focus on the positive.” The siege has become “more mental and internalized,” she said. For her, the survival technique is evading that box that is affected by borders and the siege with blogging and other IT enterprise. Gaza City hotelier Jawdat Al Khodary said much the same thing. “People are fed up with politics and are looking how to improve their daily lives. If they have skills, they can get work.”

These coping strategies and this hopefulness seem to me to be a lot of whistling in the dark. Things look worse than they did six months ago when I was here last—more garbage on the streets, more closed shops, less construction. And while Jehan told me she didn’t feel constrained by her sex at all, the statistics tell a different story. Everything that goes wrong for women in poor and depressed places happens here too. One trivial but stark visual was the offices of the Hamas-affiliated media group Airessaiah (print, web and radio station). The editor in chief, Wasam Afifa, regaled me with his liberal values and harsh critique of Hamas and then showed me around the offices. The main reporters’ space is large, light and airy; the women reporters’ room (at least there is one) is small dark and shabby. When I told Jehan and showed her the pictures I had taken, she shrugged and said, “Well, that is the culture.”

I also asked her about the lack of any palpable reaction on the street to the hunger strikers, the settlement of which was, on the day of our conversation, two days away. She said she blogs about it, but as for activism in the old sense, there is none. In fact, shop owners in Gaza City had previously been asked by local activists to close up for two hours in support of the hunger strikers. Hotelier Al Khodary told me that only two agreed to do so. He himself thought the effort fatuous. The demonstration in Gaza City—about 1,000 people—on the day the settlement was announced had been carefully managed by Hamas.

The West Bank too is remarkably quiet, apart from important but small-scale nonviolent resistance to the path of the security barrier. I asked people in the West Bank and in Israel what they make of that. Are Palestinians just ground down from oppression, knowing any protest might be (and sometimes is) met with fierce Israeli opposition? Is the footprint of military occupation getting a bit smaller, with fewer checkpoints and fewer nighttime raids? Is increased prosperity enough to make the “struggle” not worth the candle?

Palestinian Israeli human rights activist Ghaida Renawie-Zoabi was stunned by my question and a little shamed by what looks like Palestinian passivity. She promised me that she will give much thought to this question, so I am staying tuned.

Khaled Sabawi, a young Canadian-born Palestinian entrepreneur in Ramallah, credits both apparent prosperity and exhaustion. And, he says, echoing what was becoming a familiar theme, he just wants to get down to business. He has given up thinking about one state versus two states, and believes his people will gain their freedom through economic freedom and human rights, which are “more important than the flag.” He goes further and accuses Salam Fayyad and Abu Abbas of perpetuating the illusion of a dynamic Palestinian economy, which is in fact systemically dependent on donor aid.

Regarding the continuing struggle for a Palestinian state, Sari Nusseibeh, now president of Al Quds University in East Jerusalem, made much the same point several years ago. Forget statehood for now, he urged. Focus on human rights and improving day-to-day life. Nusseibeh was never a nationalist, and so he was always an odd duck in the Palestinian nationalist struggle, but this thesis marginalized him even more.

Yesterday, I had a (perhaps historic) conversation in Gaza with nine Islamists, eight of them Hamas members or supporters, in which we spoke for over two hours about the American Jewish community. We spoke of the anti-occupation tool of massive nonviolent resistance. They told me that just as the second intifada was not launched until Arafat approved it, no mass non-violent demonstrations will be allowed anywhere in Palestine until President Abbas gives his hekhsher. Which he will not, they assured me, knowing the risk that such demonstrations could turn violent and perhaps be directed against the Palestinian Authority itself.

What about mass protests in Israel? Activists are gearing up for another summer of social protests focusing on economic inequality. However, no one has confidence that the protest leaders will explicitly connect social gaps with the price of occupation. And more surprising to me, plenty of traditional lefties and long-time peace activists do not condemn that strategy.

Dan Goldenblatt, new director of the Israel Palestine Center for Resarch and Information (IPCRI), told me that all his life, he had believed in the “two states or bust” paradigm. Now, he and a group of intellectuals he is leading are at least starting to imagine alternatives, alternatives that will afford human rights and dignity to Palestinians.

I for one have not given up hope, but I believe the keys, or at least one of them, is in the hands of the Palestinians themselves, in the form of the very collective action that seems so out of reach—but is it?

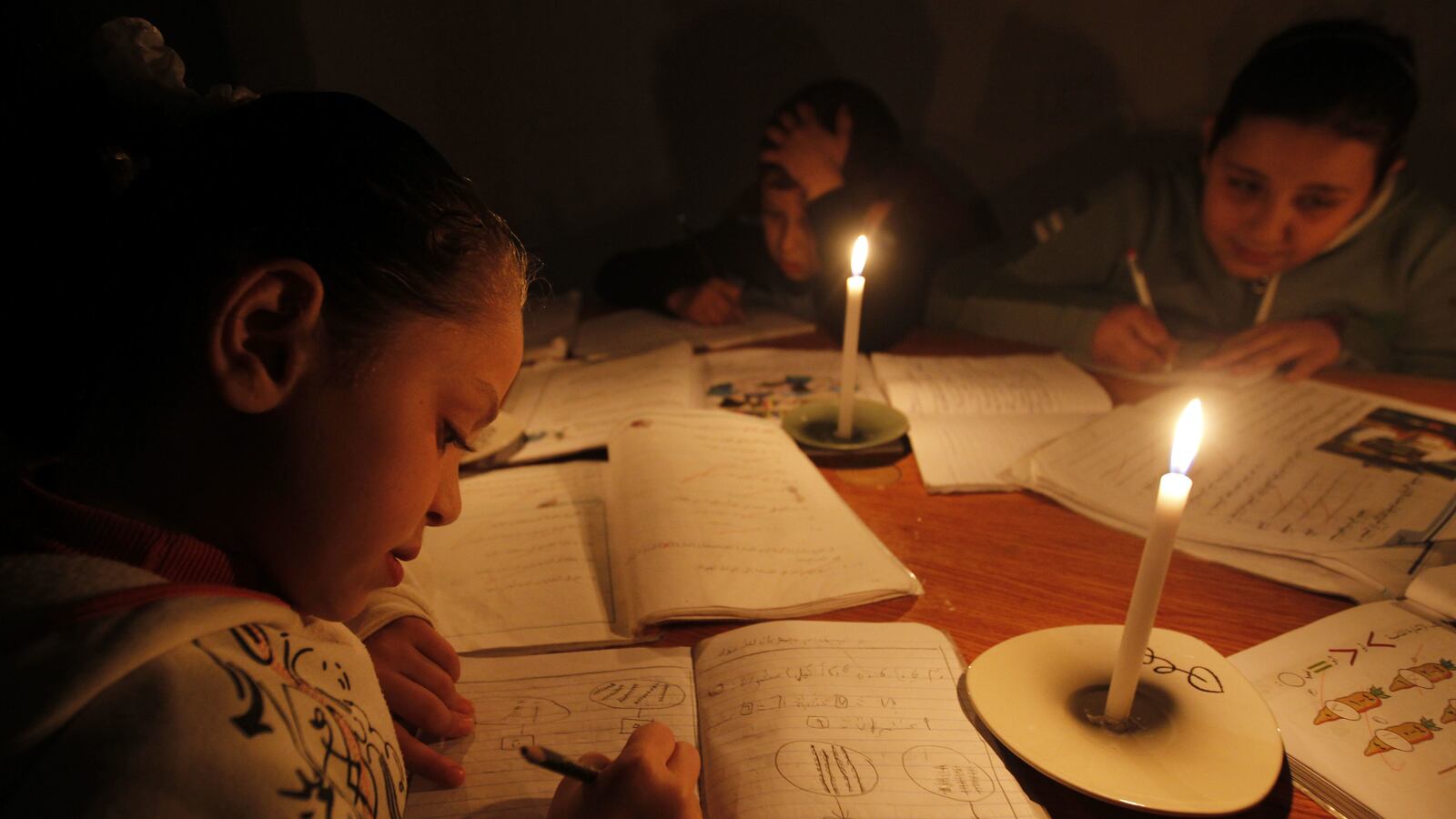

My hotel in Gaza City has 80 rooms. Eight are occupied. There are blackouts repeatedly throughout the day and night and blocks of time with no electricity at all, due largely to the decreased fuel supplies from Egypt. A meeting I had on the twelfth floor of an office building could not be scheduled in the morning because there is no electricity until 11 AM.

Gazans, who have been tolerant of siege-related deprivation because they regard it as collective punishment from Israel, are now blaming Hamas for the current fuel crisis. “After five years, the government has a responsibility,” Afifa, the newspaper editor, said.

If I ever heard a universal message, that was it.