As nearby volunteers in reflective vests and medical-grade face masks swept broken glass and righted overturned trash cans in Wilmington, Delaware, earlier this summer, former Vice President Joe Biden promised to heal the pain of civil unrest sparked by racist violence.

“We are a nation enraged, but we cannot allow our rage to consume us,” Biden vowed, one day after a night of protests and scattered vandalism in Wilmington, in reaction to the death of George Floyd at the hands of police officers in Minneapolis. It was Biden’s first major public appearance since the coronavirus pandemic sidelined his campaign for the White House months before, and a prime opportunity for him to reiterate his pledge to “restore the soul” of America. “We are a nation exhausted, but we will not allow our exhaustion to defeat us.”

It was a speech that Biden could have given in the same spot more than half a century earlier, as the same street in Delaware’s capital city was being burned in riots and patrolled by hostile National Guard troops, when Black residents feared that every trip outside could result in harassment, detention, or death at the hands of law enforcement, as many decades later still do.

“The most beset neighborhood in Wilmington, specifically the 39-or-so blocks people now call ‘West Center City,’ is the one where most of the pictures of fires and guardsmen aiming weapons originate—it is also, along the east edge, where protests were put down with tear gas this summer after George Floyd’s murder,” said Dr. David Teague, a professor of literature at the University of Delaware. “That neighborhood is still being punished for its resistance to the violence that ended Dr. King’s life.”

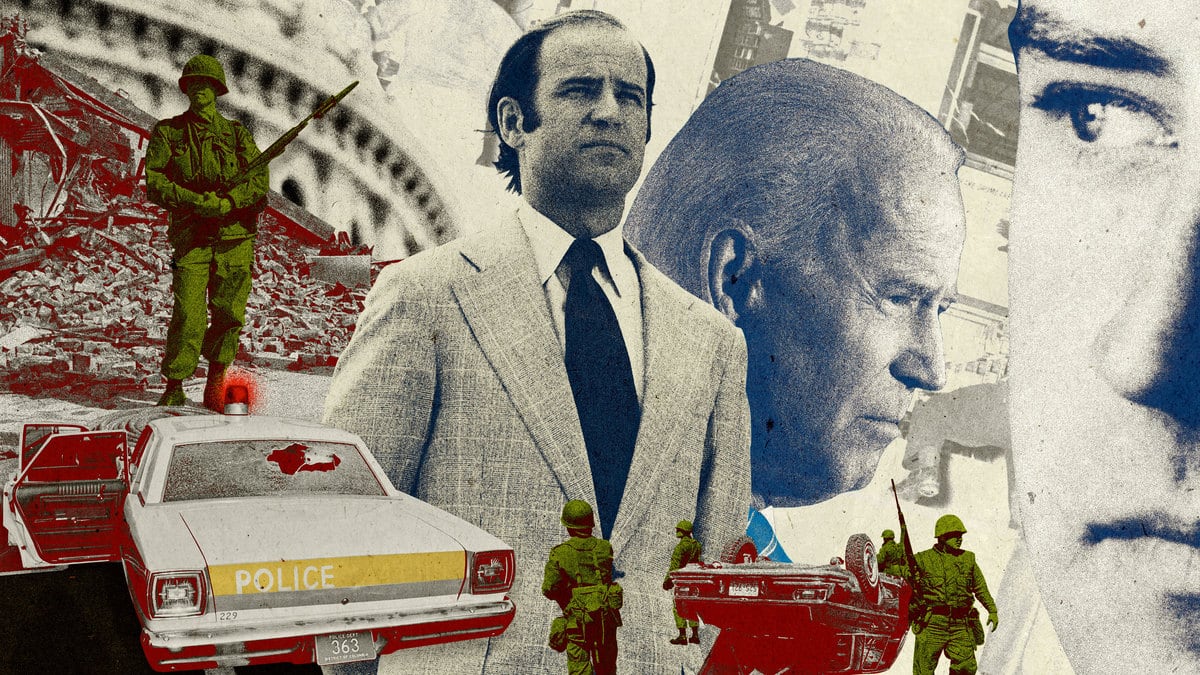

The Wilmington riots of 1968, and the subsequent occupation of the city’s Black neighborhoods by Delaware’s Army and Air National Guard for more than nine months, are a foundational part of the city’s history—and of Biden’s own understanding of the role that law enforcement has historically played in fanning the flames of racial inequality, both in his adopted home city and across the nation he hopes to lead.

More than five decades later, as racial justice in policing has become a top priority for Democratic voters and as President Donald Trump pitches himself as the “law-and-order” candidate who will save America’s cities from chaos, the lessons Biden learned from the sidelines of the Wilmington occupation—he once called himself “a suburbanite kid who got an exposure to Black America in my own city”—are again coming to the fore of his campaign.

This time, however, Biden won’t be a bystander.

It began, like many protest marches before and since, with an act of heinous violence by a white man against a Black man.

The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis on April 4, 1968, shook cities across the country, as a national outpouring of grief erupted into anger. Civil unrest rocked more than 100 cities across the country, including Chicago, Baltimore, and the nation’s capital. Wilmington, Delaware, where years of discriminatory housing and policing practices combined with the artificial division of the city along racial lines by I-95 had prompted the state’s governor to create a commission to evaluate the risk of a riot (the verdict: extremely high), was no exception.

Four days after King’s murder, an initially peaceful march primarily composed of young men took to Market Street, in the heart of commercial Wilmington. But a brick thrown through the window of a business at Fourth and Market Streets ignited the crowd, and anger over King’s assassination—and over what the Investigative Committee on Cause of Civil Unrest described as “the fact that thousands of Delaware families are compelled to live in houses which are unhealthy, unsafe, and demoralizing to dignity”—boiled over. By midnight, more than a dozen businesses had been set ablaze, nineteen had been looted, and at least fifty protesters had been arrested.

The next morning, in a bid to restore “law and order,” the state’s Democratic governor, Charles Terry, activated Delaware’s entire National Guard, with nearly a third of its 3,800 enlisted men deployed to the Black neighborhoods of Wilmington. There they remained for nine months and two weeks, the second-longest occupation of an American city by National Guard troops since the end of the Civil War.

Though the riots were eventually calmed, and despite calls from the city’s mayor that policing be returned to actual police, the Guard remained. Terry, a Southern-style Democrat nicknamed “The Great Divider,” feared that Wilmington could quickly plunge into chaos, refused to lift the state of emergency, and pushed harsh new “anti-rioting” laws through the state legislature.

The guardsmen, who were mostly from the state’s conservative southern reaches and who had no experience in urban policing, dubbed themselves the “Rat Patrol” after a popular television show about American troops who patrolled the North African desert to fight Nazis. As their successors would be accused of doing during the George Floyd protests half a century later, the inexperienced guards harassed Black residents of Wilmington’s West Center City neighborhood, detaining pedestrians on the flimsiest of pretexts and threatening them with violence at the slightest provocation.

“Man, the pigs tried to run me over,” one child told a local alternative newspaper during the occupation. “They point their guns at you and call you ‘black motherfucker.’”

Less than three weeks after the occupation began, 35-year-old Douglas Franklin Henry Jr. was shot and killed by a guardsman, and though prosecutors sought manslaughter charges, a grand jury declined to consider.

Residents were so terrified of the occupying guardsmen that a local organization produced a 13-page booklet to help Black people avoid death at the hands of law enforcement.

“Because you are black, this booklet is important to you,” the booklet, titled Black Survival Guide, or How to Survive a Police Riot, told readers. “It may help save your life.”

As the occupation dragged into the summer and early autumn, Terry continued fighting protests that no longer existed, alienating many of the city’s residents—including a young Joe Biden, who had grown up in Wilmington and returned as a newly minted attorney weeks after the occupation began, dodging guardsmen as he worked in a right-leaning corporate law office downtown.

“Every day I went to work... I walked by six-foot-tall uniformed white soldiers carrying rifles. Apparently they were there to protect me,” Biden later wrote in his 2008 memoir Promises to Keep. Though Wilmington’s white population, safely cosseted in well-to-do suburbs, were largely happy that the Guard was there, Biden recalled, “in the black neighborhoods of East Wilmington, residents were afraid. Every evening National Guardsmen were prowling their streets with loaded weapons. Curfews were in effect from dusk to dawn. Mothers were terrified that their children would make one bad mistake and end up dead.”

Biden’s flirtation with joining the Republican Party at the time—he once said that he “thought of myself as a Republican for six or seven months”—was in response to the state Democratic Party’s continued support of Terry and his stance on race relations. In the end, Biden registered as an independent.

“I was really upset with the Democratic Party in Delaware because of its perceived position on civil rights,” he told a reporter during his first run for the White House, “but I couldn’t bring myself to register as a Republican because of Richard Nixon.”

On the 2020 campaign trail, Biden has frequently returned to the images of a city under martial law, with guardsmen barely out of high school policing terrified Black residents with bayonets, as a rejoinder to Trump’s increasing rhetoric that he is soft on crime.

“I came home and my city is the only city in the United States of America occupied by the military since Reconstruction for ten months,” Biden recalled earlier this week in Kenosha, Wisconsin, where riots erupted after the police shooting of a Black man, much as unrest followed the death of Douglas Franklin Henry 52 years earlier. “Every single corner with someone, a military person standing with a drawn bayonet.”

That daily walk to work through occupied Wilmington, Biden says, changed the direction of his life. No longer content to help the city’s most prominent businesses push money around, he decided to change career tracks to become a legal advocate for the people the National Guard were policing.

“I walked across Rodney Square and into the basement of a three-story building, and applied for work in the public defender’s office,” Biden wrote in Promises. “It was the first time I felt like I was an actor in upholding the Constitution. Most of the clients I drew were poor African Americans from East Wilmington, and whether they were guilty or innocent, I did my best to make sure they were well represented at trial.”

In the decades since, Biden has adamantly declared that the America of the 21st century is different from the one where a racially divided city was under martial law for the better part of a year.

“America in 2019 is a very, very different place than the 1970s, and that’s a good thing,” Biden said last July. “I’ve witnessed an incredible amount of change in this nation, and I’ve worked to make that change happen. And yes, I’ve changed also.”

But the Wilmington of 2020 is still shaped by the Wilmington of 1968.

“The riots had an absolutely devastating negative impact on the city,” said Jim Baker, who served as Wilmington’s mayor three times, in an oral history of the riots. “I-95 had a devastating negative impact on the city. Urban renewal had a devastating impact upon the city. So take those things together, and, literally, you tore your city apart.”

The symmetry between that moment in 1968 and the one he faces now is startling, particularly as Trump attempts to redefine the general election as a referendum about “law and order.”

“The ‘suburban housewife’ will be voting for me,” Trump tweeted in August. “They want safety & are thrilled that I ended the long running program where low income housing would invade their neighborhood. Biden would reinstall it, in a bigger form!”

But Trump, like Terry before him, may be attempting to rally his base at the risk of alienating the voters who deliver elections. After seven wearying months of occupation, Terry lost his bid for reelection by a narrow 2,500 votes, and his Republican successor, who later recalled “the National Guard on the streets was by far the biggest issue in my campaign,” was successfully lobbied into pulling out the troops hours after his inauguration in 1969.

The lessons of 1968 are ground zero, Teague said, for a “radical re-vision” of how the U.S. addresses racial inequality in policing—and the lessons apply to both Biden and Trump.

“Wilmington, the 1968 resistance, the occupation, the aftermath—what all that does, 52 years later, is put Black lives and all the reasons they must matter and all the opportunities to make that happen in one small place in Joe Biden’s state,” Teague said. “I do think real commitment to radical intervention should well start at home for Joe Biden.”