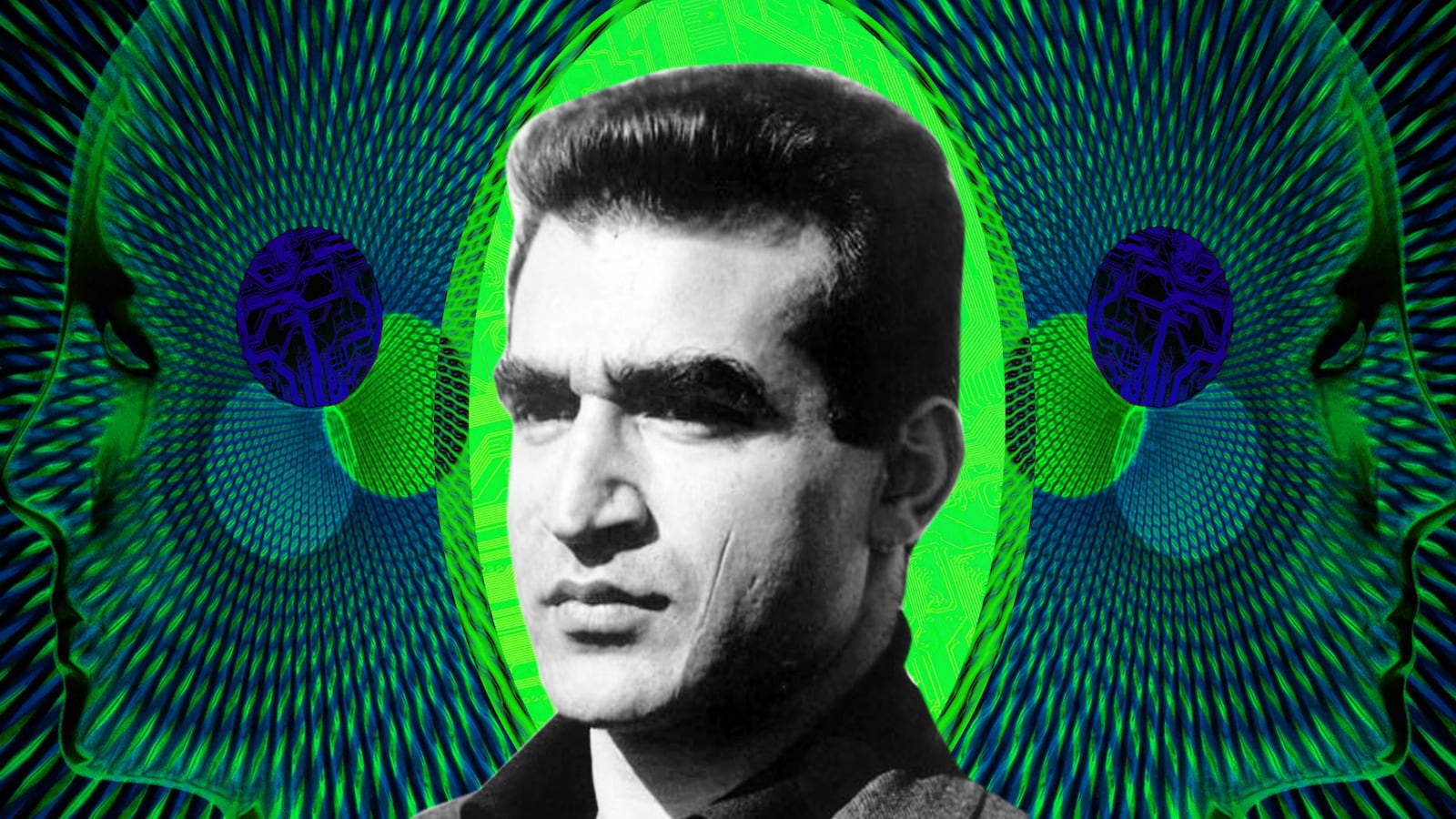

In the mid-1970s, the philosopher and former Olympic wrestler Fereidoun M. Esfandiary changed his name to FM-2030—combining the year he would turn 100 years old with an abbreviation which variously meant Future Man, Future Marvel, or Future Modular, and also happened to be his initials. To FM-2030, conventional names symbolized weighty cultural baggage. He believed markers like “ancestry, ethnicity, nationality, religion” would become irrelevant in the near future, when technological progress allowed humans to become synthetic “post-biological organisms” who lived forever. As proof of concept, FM-2030 had himself cryogenically frozen in amorphous ice at the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in 2000, after a battle with pancreatic cancer. Of his future revival, he told The Palm Beach Post: “I’ll be so glad that I’m back.”

A decade out from the year when he claimed “everyone will have an excellent chance to live forever,” FM-2030 has not yet been revived. But his story has come back in the form of an odd independent movie called 2030: The Film. The feature was directed by and stars a British corporate filmmaker named Johnny Boston, who met the transhumanist as a child and later became his friend. With the help of his marketing film crew and FM-2030’s longtime friend, Flora Schnall, Boston sets out to chronicle the reanimation process of the futurist’s frozen corpse.

The movie is framed as non-fiction—and was submitted to four film festivals as a documentary—but what emerges is a confused hybrid of real subjects speaking evidently scripted dialogue, “secretly” recorded interviews that either flouted recording consent laws or were conducted with actors, and events that, technically speaking, never happened (the lab in the film successful revives a cryogenically frozen pig). “I don’t love to mention it,” Boston said, “but yes, we did script it.”

At its best, the movie’s flexible relationship with fact could force the viewer to loosen their idea of what’s possible—the effect FM-2030 hoped his theories might have on the public. But if that was Boston’s intent, it gets lost in its execution and his frequent digressions on himself. After a brief voiceover of an archival FM-2030 speech, the movie spends the bulk of its first act introducing not FM-2030, but Boston and his artistic dissatisfaction with corporate work. A full chronological biography of FM-2030 never comes, replaced by a bizarre subplot in which Boston casts himself as a pathological liar who earnestly believes in cryogenics. Over the course of the film, Boston uncovers an apparent, but little explained conspiracy at the cryonics lab, and then abruptly alienates Schnall, leaves his wife, misses his kid’s ballet recital, accuses one of the scientists of having a workplace affair, and briefly plots an escape to Israel (?) after discovering the lab has been spying on him, only to never mention it again. The end of the film I won’t spoil, but let’s just say, things come alive.

Arguably the most confusing aspect of 2030: The Film is that the real story of FM-2030’s life needed no elaboration. Born to an Iranian diplomat in Belgium in 1930, the transhumanist had lived in 17 countries by the age of 11. By 18, he had picked up four languages (Arabic, French, Hebrew, and English), and represented Iran at the 1948 Olympics in basketball and wrestling. After college, he served on the United Nations Palestine Commission for two years. In the following decades, FM-2030 authored three novels, dozens of essays, and three transhumanist manifestos: Optimism One, Telespheres, and Are You Transhuman?

Among his theories, FM-2030 believed that marriage was an arcane convention of ownership, that nuclear families would transition to modular communities called “mobilia,” and that political distinctions like the left and right would be replaced by ideological “upwingers,” meaning those who looked to the sky (the future), and “downwingers,” or those who looked to the earth (the past). A few of FM-2030’s ideas were spot-on. In the mid-1970s and ‘80s, FM-2030 predicted genetic modification, in vitro fertilization, teleconferencing, telemedicine, teleshopping, and 3D printing—then such an absurd thought that, in his obituary, The New York Times described the idea as a “Santa Claus machine.”

Many of FM-2030’s ideas could be worth reconsidering now, in the middle of a pandemic and raging climate crisis, which scientists have warned will wreak irreversible catastrophe if emissions aren’t slashed in time for the year he held in such high esteem.

FM-2030’s manifestos had elements of social progressivism. He believed in the unification of global social movements and shedding phrases like “illegal immigrant” in favor of less nationalistic ideas of personhood. But those same texts could easily turn naive, sinister, or hypocritical. In Optimism One, for example, he preached a transcendence of divisive “isms”—nationalism, totalitarianism, socialism, capitalism—in favor of optimism. Around the same time, he consulted for the defense contractor Lockheed.

“Esfandiary’s brand of transhumanism advocated a deliberate and aggressive acceleration of the pace at which human science and technology took positive control of the world,” Greg Klerx wrote in an essay called The Transhumanists as Tribe, “controlling weather cycles, manipulating human biology and colonising planets were just the beginning.”

But 2030: The Film doesn’t grapple with the gray areas of his ideology. Boston lingers instead on one-dimensional ideas of immortality without asking what use it serves, when the problems FM-2030 thought the future would solve—poverty, public health, political or nationalistic divisions—may be more heightened as ever. An honest and thorough consideration of FM-2030’s ideas could well be worthwhile. But for now, the comeback will have to keep waiting.