The ongoing debate 29 years after he died about whether the radical journalist I.F. Stone was a Soviet spy is yet another embarrassing partisan dustup that makes leftists look soft on Soviet Communism and rightists look hostile to good journalism.

The question is also secondary—like emphasizing Babe Ruth’s pitching. I.F. Stone carved out his reputation most dramatically, week by week, from 1953 through 1971, as he and his wife Esther produced his four-page Washington newsletter. This Mom-and-Pop newspaper operation peddled truth, demanded justice, and defied convention as journalism turned corporate, conformist, consumerist.

Stone believed that radicals should be iconoclasts—rejecting truisms, left and right. He believed journalists should be independent—beholden to no bosses to bully them, no sources to massage them, no peers to pressure them. And he proved that defending democracy required vigilance, range, and creativity.

“Izzy” Stone crusaded for his egalitarian Marxist socialism and Peter Kropotkin anarchism by partnering with his wife in an eminently capitalist small business. Churning out their mischief-making pamphlet weekly, they paid their bills on time, keeping a balanced bottom line.

Stone’s subversive liberalism was so freewheeling that if, in a nearly seven-decade career which championed black rights and workers’ dignity, free speech and advocacy journalism, he initially succumbed to KGB charms, it only makes his subsequent denunciations of Soviet oppression and New Left hooliganism more impressive.

“Izzy” Stone wasn’t the only one to look owlish, think dovish, yet act hawkish when defending basic civil liberties and America as an imperfect but perfectible democracy. He just did it better and louder than most.

While an American original, Stone also typified one strand of Eastern European Jewish immigrant to America: he was Isidore Feinstein from his birth in 1907 until his legal name-ectomy in 1938. Boatloads of Russian and Polish Jews arrived from the 1880s through the 1920s, quoting the Hebrew prophets, seeking Socialist Revolution, yet trusting America to let them think freely, politic aggressively—and often even earn handsomely.

Recalling his thoughts when Establishment reporters and politicians insulted him, Stone captured that unique identity cocktail: “I used to walk across the lawn at the Capitol and I would think, ‘Screw you, you sons of bitches. I may be just a goddamn Jew Red to you, but I’m keeping Jefferson alive!’”

Before he could vote, Stone was already reporting on politics and crusading from the left. Like many comrades in the 1920s and 1930s, Stone had inexcusable blind spots regarding Soviet Communism and Joseph Stalin. His passion for economic reform and fury at his government’s resistance softened him too much on the alternative, probably making him a “useful idiot” in the 1930s.

Stone’s accusers, especially the historians John Earle Haynes and Harvey Klehr, conclude convincingly, based on summaries of KGB documents, “that in the last half of the 1930s Stone assisted the KGB in several ways—serving as a talent scout for new sources, a courier linking the KGB with sources, and a source in his own right for insider journalism information.” Even Stone’s defenders acknowledge that “What he did do was meet with Soviet agents working under cover in the 1930s and ’40s and exchange information with them.”

We need not follow other defenders to dictionary.com to determine what constitutes “spying.” Stone’s speciality was being an outsider with no inside info: he wasn’t Alger Hiss betraying the State Department or Julius Rosenberg peddling state secrets. Stone’s bigger sin was shilling for Soviet totalitarianism in the 1930s; the redemption came from defying his leftist friends after visiting Russia.

“I feel like a swimmer under water who must rise to the surface or his lungs will burst,” he wrote in 1956, while millions—and many of his fans—remained deluded. “Whatever the consequences, I have to say what I really feel after seeing the Soviet Union and carefully studying the statements of its leading officials. This is not a good society and it is not led by honest men.”

Thus, at the height of his influence, from the 1950s through the 1970s, when I.F. Stone's Weekly then I.F. Stone’s Bi-Weekly, scooped colleagues, embarrassed politicians, and thrilled liberals, his lapses from the 1930s no longer affected his judgment.

I.F. Stone wasn’t always right—but he was always forthright. He was ahead of America regarding the wrongs of Joe McCarthy, the lies behind the Vietnam War, and the righteousness of civil rights—although he considered Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech “a little too saccharine.” He was correct in championing Zionism and Palestinian nationalism; although after 1967 he judged Israel too harshly. And he nailed it when writing: “If God as some say now is dead, He no doubt died of trying to find an equitable solution to the Arab-Jewish problem.”

The National Press Club blackballed Stone for trying to host a black guest in the 1950s. In the 1960s, he risked his popularity with the New Left by repudiating mob violence. And he always remained grateful for the First Amendment protections he enjoyed. Even though he resented the harassment J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI inflicted, he could recall that: “It speaks well for the tradition of a free press in our country that even in the heyday of McCarthy it was possible for me to obtain my second-class mail permit without trouble.” He acknowledged: “There are very few countries in which you can spit in the eye of the Government and get away with it. It’s not possible in Moscow.”

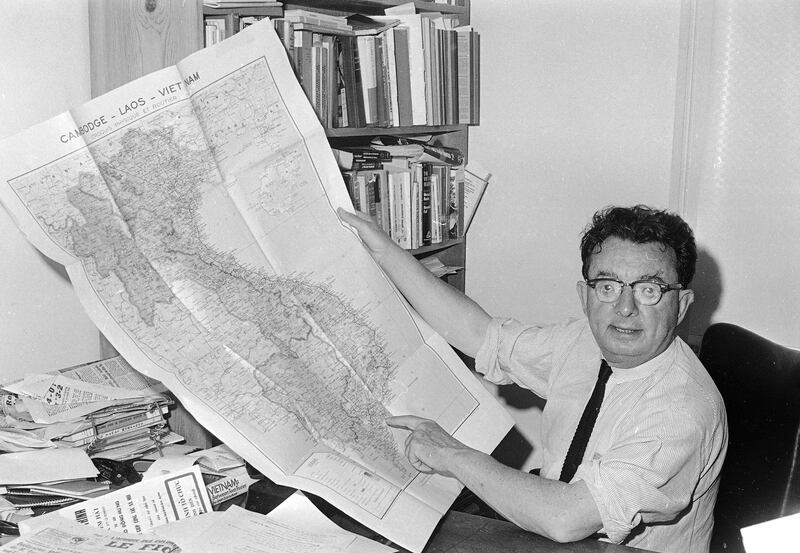

I.F. Stone holds a map of Vietnam and Southeast Asia while working at his Washington home May 12, 1966.

William J. SmithI.F. Stone was correct to assume that “all governments are run by liars” and that “You’ve really got to wear a chastity belt in Washington to preserve your journalistic virginity. Once the secretary of state invites you to lunch and asks your opinion, you’re sunk.” Most American newspapers are too addicted to vulgar sideshows to generate advertising dollars, instead of pursuing truth. And his obsessive, encyclopedic, method of sifting through different government press releases seeking contradictions, often yielded journalistic gold—especially when he discovered in the late 1950s, that underground A-bomb testing triggered seismic responses felt 2600 miles away not merely 200 miles away as government spokespeople first claimed.

But today, with the cable-bog and the blogo-swamp boosting shrill, egotistical, partisan journo-hacks, I.F. Stone’s role in treating journalism as political advocacy is worth debating. His aims were noble: “A newspaperman ought to use his power on behalf of those who were getting the dirty end of the deal... And when he has something to say, he ought not to be afraid to raise his voice above a decorous mumble, and to use forty-eight-point bold.” But when does politicking become axe-grinding not truth-telling?

When he turned 64, on Dec. 6, 1971, Stone announced: “the compulsion to cover the universe in four pages has become too heavy a burden.” He had met many of his goals. “I wanted the paper to have readability, humor and grace,” he wrote. “I dreamed of taking the flotsam of the week’s news and making it sing. I had a vision of a paper which would be urbane, erudite and witty.”

Characteristically, he also expressed his “gratitude to my wife, Esther.” He declared: “Her collaboration, her unfailing understanding, and her sheer genius as a wife and mother, have made the years together joyous and fruitful.”

That wonderful romantic and professional partnership explains I.F. Stone’s success. The journalist and publisher Peter Osnos, who, when just starting out, worked for Izzy, reveals that Izzy and Esther usually celebrated putting the newsletter to bed with dinner and a movie, while their summer vacations often included dancing night after night. Esther said: “Izzy never looks back. He has a zest for life, for every new day, that I've never seen in anyone else.”

Osnos saw how Stone’s love of life and for his wife balanced his professional crankiness: “Izzy entertained his readers and forced them to examine their beliefs. This refusal to be doctrinaire and his exuberance (despite the sometimes intimidating erudition that went with it) was a vast asset to his expanding circle of readers).”

The Esther-Izzy bond shows that Izzy Stone loved human beings and humanity. That warmth distinguished him from yesterday’s violent fanatics and today’s partisan bullies. Ultimately, Isidor Feinstein infused his dark, tortured, heavy-handed intellectual and ideological Eastern European heritage with American lightness—and love. The result was Izzy Stone, crusader and comrade, literary stylist and American individualist, a down-to-earth Brainiac who exulted: “I am having so much fun I ought to be arrested.”