They told him he would be safe with them. They promised to get him out of the city. He only wanted to go home, the boy said, as he climbed into the vehicle and ducked out of sight. He was too young to die.

But, to the 16-year-old behind the wheel, the kid lying on the floorboard wedged against the backseat knew too much to live.

Nobody in the car—not the driver, his brother or the doe-eyed boy—was aware of the political winds that would engulf them. They were not students of public policy and, if questioned, they could not likely call the names of those who would use their lives as fodder for the sweeping legislation being pushed in Washington. They well understood, though, the calculus of the streets, where living was harder than dying and any day could well be their last. And, that some secrets were better left buried.

The sedan crept along East 108th Street and came to a sudden stop at South Dauphin Avenue, near the opening of a railway underpass. The boy was ordered out of the vehicle and into the viaduct tunnel. As he stepped forward and into the darkness, there were no tears, his killers would later testify. There were no shouts, no wails, no final pleas for his life as he instinctively faced a wall emblazoned with gang graffiti and dropped to his knees knowing these moments would be his last. The .25 caliber bullets tore through the back of his small skull, his brain matter flung among the dirt and shards of broken glass. Chicago police discovered the body minutes later, just after midnight, crumpled over in a puddle.

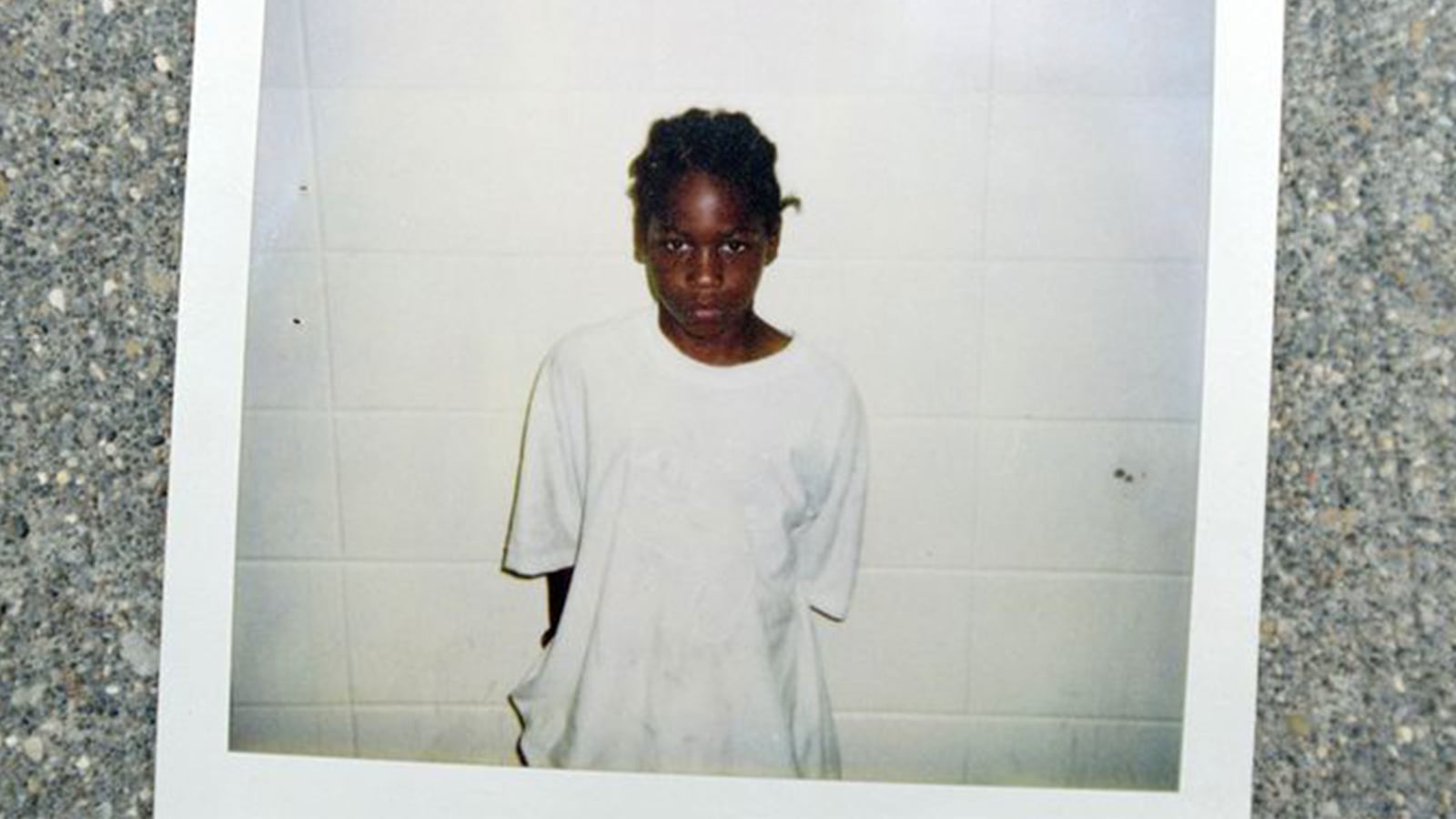

It was an assassination, a hit ordered by Chicago’s Black Disciples in an attempt to silence a potential informant. The victim was 11 years old, wearing a Tasmanian Devil T-shirt. An elementary school drop-out, known as “Yummy” because he loved cookies, Robert Sandifer would be featured on the cover of Time magazine as his brief life, and violent death, informed decades of domestic public policy.

Family and friends gather around the open casket, touching Yummy Sandifer’s face.

Steve Liss/The LIFE Images Collection via GettySandifer was one of more than 900 murder victims in Chicago in 1994, as the nation was grappling with what lawmakers said was a continued rise in violent crime committed by juvenile offenders. The boy in the back of the car would come to symbolize all that was said to be wrong in black America.

Accused of shooting three teenagers, and killing one of them, Sandifer had been the subject of a city-wide manhunt that expanded over three days across state lines when he was spotted around 11:30 p.m. on Aug. 31 by teenagers Cragg and Derrick Hardaway. He was sitting on a friend’s porch, waiting for his grandmother, when the brothers lured Sandifer away. Before the sun would set again, the Hardaways would be in police custody for his murder.

Within days of the grisly killing, on Sept. 13, President Bill Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act into law. Over 2,000 people attended the ceremony, including members of Congress, mayors and top law enforcement officials. He called it a step toward “bringing the laws of our land back into line with the values of our people and restoring the line between right and wrong.” The story of a little boy, shot execution-style, almost certainly loomed over the crowd.

There could be no more, they said.

Commonly known as the Crime Bill, the $30 billion omnibus legislation set the country on a path to the mass incarceration of African-American men and boys, creating a school-to-prison pipeline that led to record profits for private prison operators and the destruction of social structures in predominantly black neighborhoods. At the time, the White House and Congressional leaders bathed themselves in an ocean of support from black elected officials, as well as faith and business leaders. Chicago, then and now, was regarded as ground zero.

Then Sen. Joe Biden was the chief architect of the bill. Sen Bernie Sanders, who never saw a piece of a crime bill he would not support, voted for it. The law did not simply provide for $9.7 billion for federal prisons, billions more for state-run correctional facilities and battalions of new police officers. It instituted the death penalty for 60 new federal offenses and provided “enhanced” sentencing guidelines for dozens more. It incentivized state-level criminal justice systems to lock up more people for longer periods of time while eliminating inmate education programs.

With little debate, it lowered the age at which a child could be charged as an adult in federal court. The majority of those cases involve children of color and, today, two-thirds of Americans who receive life sentences as juveniles are black. Ironically, the first juvenile court in the United States was established in 1899 in Cook County—100 city blocks from the underpass where Sandifer was murdered.

States across the country would follow the federal government’s lead and lower the age at which a juvenile could be adjudicated as an adult to as low as 13 without any meaningful evaluation of their fitness to stand trial. In some states, there is no minimum age for certain crimes, including homicide.

The national discourse around criminal justice reform in the early 1990s never addressed the foreseeable negative outcomes of those policy decisions. The collateral damage stemming from the supposed war on violent crime would devastate communities for generations. Violence wasn’t discussed as a public health question, but as a result of the moral failings of a failed culture. If black people could not police themselves, they needed to be more heavily policed, locked up and kept out of society. And that included children.

Ultimately, violent crime rates went largely unaffected despite the billions spent under the 1994 crime bill and its renewals since. Studies show the legislation had, at best, a marginal effect on improving public safety—and no impact on the number of juvenile offenders.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton’s inability to account for her support of the bill dogged her throughout the primary. Her loss in the general election—by just 80,000 votes spread across three states—can be blamed, in part, on a lack of enthusiasm among African-American voters.

But in 2020, on the 25th anniversary of its passage, every major Democratic candidate has put forth a plan they say will turn back the tide—at least on the federal level. Some of those platforms include abolishing mandatory minimum sentencing, eliminating the death penalty and solitary confinement, and banning private prison contracts. While most agree that marijuana should be legalized, not every candidate has a plan to release and expunge the records of those currently serving time for non-violent drug offences in the federal system.

It must be said that none of the candidates came to these policy positions on their own. Every one of them was pushed. Pushed by front-line activists and social-justice organizers, pushed by think tanks and scholars who have invested themselves in identifying more avenues for restorative justice, and pushed by voters tired of footing the bill for a system that does more damage than good. Pushed by the tragic lives of young black boys like Yummy Sandifer.

Hailed as a symbol of the gang problem plaguing inner cities, failing social safety nets, and the inadequacies of the juvenile justice system, Sandifer’s brief life was used as a cudgel against black-on-black crime. For policymakers, he was the very embodiment of the mythical super-predator—one of seven siblings born to a welfare-dependent crack addict and an absent father. No stranger to county social workers, the diminutive brown boy with nickel-sized dark eyes had been accused of more than 20 felonies and five misdemeanors before he allegedly shot three teenagers in the Roseland section of Chicago.

“He was a crooked son of a bitch,” a local store owner told Time magazine in 1994. “Always in trouble. He stood out there on the corner and strong-armed other kids. No one is sorry to see him gone.”

Witnesses say Sandifer opened fire with a 9-millimeter semiautomatic handgun, shooting into a crowd, wounding two teens and killing a third that day, before he disappeared. Investigators contend that little Yummy was shooting in the direction of the Black Disciples. He never faced charges for prior behavior because, at 9 and 10 years old, he was too young even for juvenile court, and too dangerous to be housed with children his age.

In all of the coverage of the day, no one talked about what might have been done to prevent the tragedy. There is no mention of long-term mental health services or other interventions that might have made a difference for the Sandifer family, even though it was clear to anyone to encountered him that the boy’s life was in peril.

Lorina Sandifer, Yummy Sandifer’s mother.

Steve Liss/The LIFE Images Collection via GettyHis mother, Lorina, had over 30 arrests for drug possession and prostitution. Already in his grandmother’s custody at 3, Sandifer had quit school by age 8 and reportedly began breaking into houses. Time after time, he was sent back to his grandmother’s house where as many as 19 other children lived. His grandmother, Jannie Fields, lost custody of the Sandifer children in 1993. Sandifer ran away from a children’s shelter the year before he died and—at 11 years old—he largely lived on the street.

The damage he suffered at the hands of relatives was well documented through the years. At the time of his death, the coroner noted nearly 50 wounds in various stages of healing, including cigarette burns. Stretched out on the medical examiner’s slab, the boy measured only four-feet six-inches.

His grandmother’s fight to keep him alive was over.

After getting a tip about where he grandson might be hiding, Miss Jannie struck out in a van the night of Aug. 31, desperately searching the streets for her daughter’s boy. He was as good as dead, she knew, if she didn’t get him into a police precinct. There was a bounty on his head.

A friend offered to call a cab and another went inside to call Miss Jannie. But, the Hardaways got to him first. The boys, only 16 and 14 themselves, coaxed Sandifer into a waiting car. By the time the young woman returned to the porch, he was gone.

Minutes later, he was dead.

Four hundred people gathered at the funeral in 1994. His siblings crowded around the casket, as Miss Jannie howled his name. Washington lawmakers would point to his life as evidence they were doing the right thing, that the Crime Bill was a desperately needed salve to staunch the tide of violent crime. Notwithstanding current campaign promises, 25 years after Yummy was found in that tunnel, the legal landscape remains largely unchanged. The cost goes well beyond the next election. The price will be another generation of Yummys, children written off, locked up or dead.

Until we give full recognition to the corrosion that continues to unfold—especially and specifically for juvenile offenders—his ghost will continue to haunt us.