In the closing weeks of this insane campaign, Donald Trump has railed against a rigged election system to cheers from his rowdy crowds. His opposite populist, Bernie Sanders, sounded a similar note in the primaries, warning about the affect of corrupt special interests and big money on our democracy. They’re not wrong.

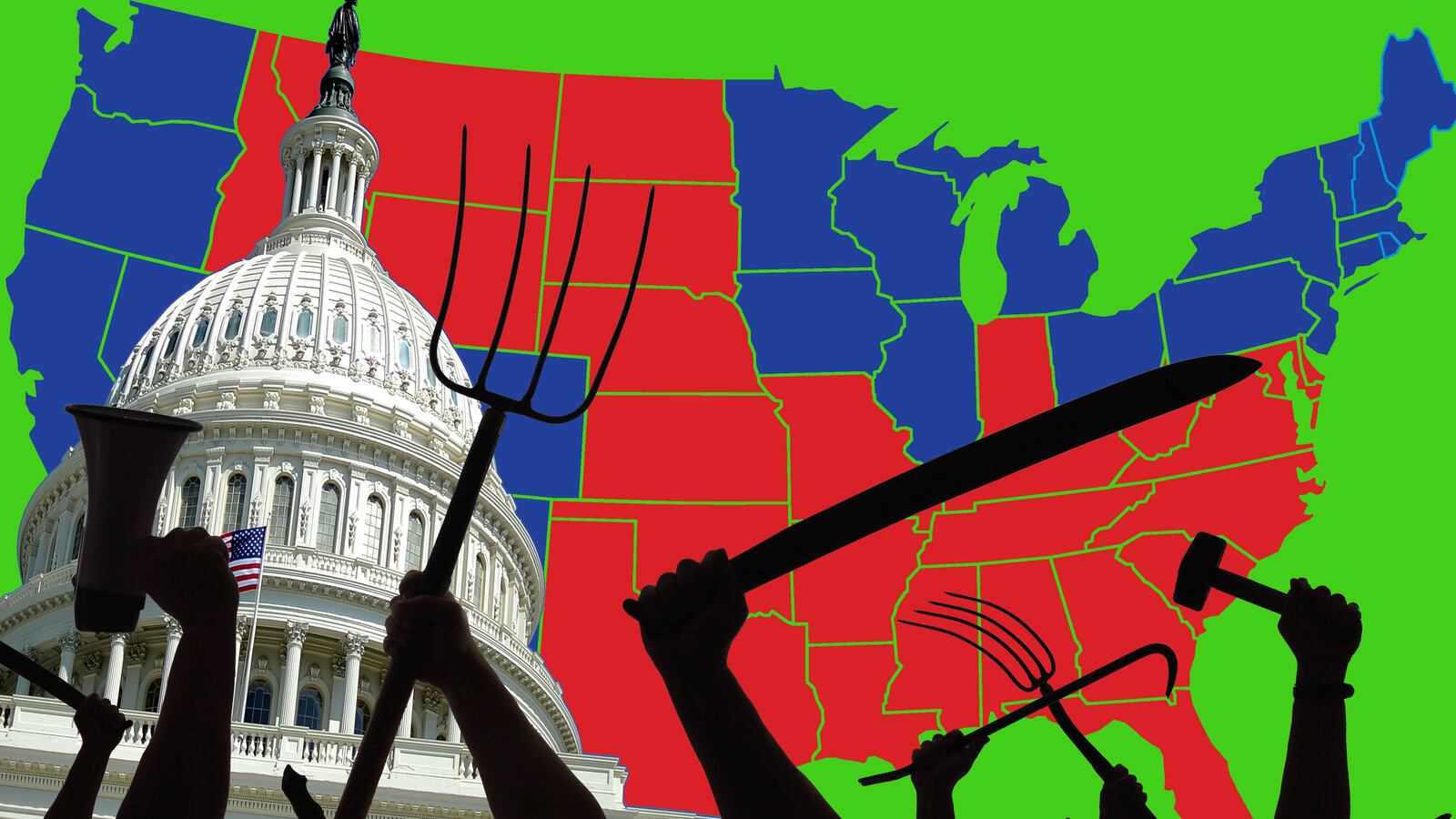

America suffers from electoral dysfunction. Our system too often obstructs maximum participation while guaranteeing un-representative results through the rigged system of redistricting.

Take this fact and choke on it: Back in 2012, Democrats won 1.4 million more congressional votes than Republicans nationwide, but the GOP retained control of Congress by a 234 to 201 margin.

That’s a national disgrace, implemented by design—one that directly leads to our dysfunctional, divided Congress and our polarized, paralyzed national politics.

But it’s perhaps not too much to hope that some of this cycle’s populist anger can be redirected into doing something constructive to fix the problem.

Forget fetishizing voter-IDs and other partisan power plays. The primary culprit is the rigged system of redistricting.

Take Pennsylvania, where Trump has called for election monitors in tones that recall rallying a posse with vigilante instincts. In 2012, President Obama won the state with 53 percent of the vote, yet Democrats won only four of the Keystone State’s 18 congressional seats. The same dynamic was seen in Virginia, where Obama won 52 percent of the vote, yet Democrats won only 27 percent of the congressional seats.

This helps explain why even on Donald Trump’s worst days, Republicans weren’t too worried about maintaining their hold on the House. Paul Ryan has a better chance of being deposed as speaker by the so-called Freedom Caucus that John Boehner called “knuckle-draggers” than of actually losing his majority.

That may be good for Republicans in the short-term, but it’s bad for our democracy. Many Democrats are salivating at the prospect of reshuffling the deck in their direction after the next Census in 2020. Unless we enact redistricting reform, though, the result will continue to be fewer competitive general-election seats, meaning incumbents have less and less incentive to work across the aisle, lest they lose their seat in a primary challenge from a member of the agitated activist class.

Which brings me to the second big election reform: open primaries. Think back to this spring, when we were all young and innocent and The New York Times didn’t use the word “pussy” on its front page.

Recall the righteous anger during the primaries when scores of Sanders supporters and even Donald Trump’s own kids found themselves effectively disenfranchised because they hadn’t changed their party registration six months before.

Independents make up 45 percent of the electorate, but in many states they are blocked from voting for the candidate of their choice, across party lines. That’s a remnant of a system designed to make it as difficult as possible to participate in closed partisan primaries so that the results would be more predictable for the party bosses.

Open primaries tend to lead to higher and more representative turnout and that means parties that are more likely to elevate candidates who are competitive in a general election. There’s an orange-hued exception to this general rule, but that’s a symptom of a larger structural problem in the GOP: their systematic RINO-hunting that left the party susceptible to a hostile takeover from conservative populists. But open primaries would increase access to the process and make it more difficult for members of Congress to simply play to the narrow primary base while ignoring the vast majority of their constituents.

Redistricting reform and open primaries are powerful cures for our electoral dysfunction, but they generally need to be implemented on a state-by-state basis.

The good news is that state reform efforts have been gaining steam. In 2014, there were more than 190 bills to expand voter rights and access introduced in state legislatures.

The bad news is that legislators are usually the last people who will back reforms that might make their re-elections more difficult. That’s why in many states, putting election reforms on the ballot in referendums has been the surest path to success.

But that doesn’t mean that a president is powerless to lead on election reform. The Brennan Center published a typically thorough set of proposals for how a president can begin to address election reform through executive orders (gasp!) in the face of all-too-typical congressional inaction.

These include reviving civics education and subsequent voter registration in schools, extending the successful “motor voter” to all federal agencies rather than just DMVs, appointing Democrats and Republicans to the intentionally deadlocked Federal Election Commission after almost a decade of congressional inaction, requesting that the Securities and Exchange Commission issue regulations that require disclosure of corporate political spending and requiring companies that are awarded government contracts to disclose all political spending.

Even in the last months of his tenure, President Obama has expressed a desire to do more with election reform and it’s heartening to see that one of the initiatives he’s signed on to help lead during his post-presidency is a redistricting reform campaign alongside his former Attorney General Eric Holder. But plenty of Democrats will resist election reforms like this if they believe that they will be in a place to rule over their own rigged system in the near future. Perhaps his post-presidential bully pulpit, which will be bigger than most, can help cajole us into common sense.

But none of these reforms address the elephant in the room—the unlimited big money flowing through our election system in the wake of the Citizens United Supreme Court decision. Trump has broken with his party to be critical of super PACs and Citizens United in the past, despite having the head of the group Citizens United, David Bossie, serve on his campaign staff. And of course overturning Citizens United has long been a priority of Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton. Even though this election has shown the power of small donors, it’s a desperate reaction to the deeper problem.

That’s why a push for a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United has been gaining momentum. The fact that both parties’ nominees have backed a constitutional amendment is, at least on the surface, a rare sign of bipartisan progress. That’s something we can build on if we have the will.

But why not propose repeal and replace? Any amendment to overturn Citizens United could be paired with positive federal election reforms, designed to open the process and provide transparency and political accountability. The details of that are a big idea for another day.

The dark irony of this election is that Main Street populists who are pissed off at the division and dysfunction of Washington have been attracted to candidates whose positions would only make the polarization worse. Their cure is pure poison.

But we have a rare opportunity to harness this bipartisan anger at the rigged system into positive action. Election reform is not a nerdish concern anymore. At this point, America’s electoral dysfunction—and the way it exacerbates polarization—has become a smear on America’s reputation for stable, good governance.

Fixing the system would help heal the wounds of this bitter and unrepresentative election, and make it far less likely that we end up here again in the elections to come.