Harlon Carter, “Mr. NRA,” the man who turned America’s national rifle club into its formidable gun lobby, knew guns could kill people—including the 15-year-old Mexican kid he blew away with a shotgun when he was 17.

Believe it or not, the National Rifle Association began in 1871 committed to “Firearms Safety Education, Marksmanship Training, Shooting for Recreation”—according to the sign displayed for years at its national headquarters. Its famous lobby sign with the edited version of the militia-less Second Amendment—“… the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed”—only came a century later.

Founded by two Civil War veterans embarrassed by Northern soldiers’ inferior marksmanship, the NRA helped pass America’s first gun control laws in the 1930s. Harlon Carter, a tough, bullet-headed conservative, hijacked this nationwide sporting club in 1977 with convention floor machinations immortalized as The Cincinnati Revolt.

Born in Granbury, Texas, in 1913, Carter was a trained lawyer who also accumulated 44 national shooting records. He led the Border Patrol from 1950 through 1957, before heading the Southwestern Region of the Immigration and Naturalization Service from 1961 through 1970. In 1954, he proclaimed “the biggest drive against illegal aliens in history,” calling it, in those politically incorrect times, “Operation Wetback.”

As NRA president from 1965 to 1967, Carter stewed as gun control became a pet cause of the ’60s radicals he hated. The terrifying urban crime epidemic, along with the John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy assassinations, helped trigger the Gun Control Act of 1968. The law banned buying guns or ammunition by mail order—as Lee Harvey Oswald had done—stopped the importing of surplus military weapons and prohibited gun purchases by drug addicts and mental patients. When asked about such dangerous individuals wielding guns, Carter deemed it “a price we pay for freedom.”

Harlon Carter, executive vice president of the National Rife Association, left, and Neal Knox, executive director for the NRA, chat before they testify on Thursday, May 4, 1978 in Washington, before the House Judiciary subcommittee holding hearings on gun control legislation.

AP Photo/DurickaIn pushing the NRA into crusading against gun control, Carter spearheaded a broader counterattack that energized conservatism, further polarized America, and elected the bête noire of the 1960s’ activists: the pro-gun cowboy, anti-hippie right-winger, Ronald Reagan.

Throughout the 1970s, the NRA’s sportsmen tried keeping their organization apolitical. They purchased 77,000 acres in New Mexico for what they called a National Outdoors Center—not shooting center. They proposed moving national headquarters from Washington, D.C., to Colorado Springs. And, reflecting Washington’s lobbying boom, they established an Institute for Legislative Action in 1975 headed by Carter. That move doomed them.

Carter wanted to “win” the gun control battle “on a simple concept: No Compromise. No gun legislation.” Unsettled by his extremism, Old Guard leaders fired 74 employees. Mimicking the left’s histrionics, evoking Watergate’s “Saturday Night Massacre,” Carter and his allies mourned this “Weekend Massacre.” Carter was too popular in the NRA to be fired. He resigned in protest—and sought revenge.

At the next annual meeting, in May 1977, Carter choreographed his Cincinnati Revolt. The rebels worked the Cincinnati Convention-Exposition Center floor wielding orange hunting caps and walkie talkies. “Beginning in this place and at this hour, this period in NRA history is finished,” Carter thundered as a rank-and-file up in arms dumped the Old Guard. He became executive vice president. NRA headquarters remained in Washington. “This is where the action is,” he explained.

Harlon Carter’s timing was perfect. The weak leadership, wild inflation, social chaos, and foreign policy humiliations of Jimmy Carter’s presidency were rousing conservatives. That year, Ed Koch, born 11 years after Carter, became New York’s mayor, vowing to impose “law and order.” In 1978, Howard Jarvis, born a decade before Carter in Utah, led the Proposition 13 Revolt against California’s crushing property taxes. And by 1980, Ronald Reagan, born two years before Carter, had won the presidency—benefitting from the NRA’s first presidential endorsement ever. These and other members of the World War II generation believed they were restoring the values, patriotism, and order that the baby boomer rebels born in the 1940s and 1950s trashed. “You don’t stop crime by attacking guns, you stop crime by stopping criminals,” Carter preached.

Paralleling this Reagan Restoration, Washington’s Golden Age of Big Money Lobbying began in the mid-1970s too. Initially, labor unions established PACs—Political Action Committees—to bundle unionists’ contributions. Thanks to the Federal Election Committee’s “Sun Pac” decision in 1975 allowing Sun Oil to solicit employees for its political PAC, corporate money started flooding independent organizations like the NRA. A year later, the Supreme Court decided in Buckley v. Valeo that the First Amendment wouldn’t permit limiting campaign spending, including independent expenditures by lobbying groups and PACs. Energized, Carter envisioned an NRA “so strong and so dedicated that no politician in America, mindful of his political career, would want to challenge our legitimate goals.”

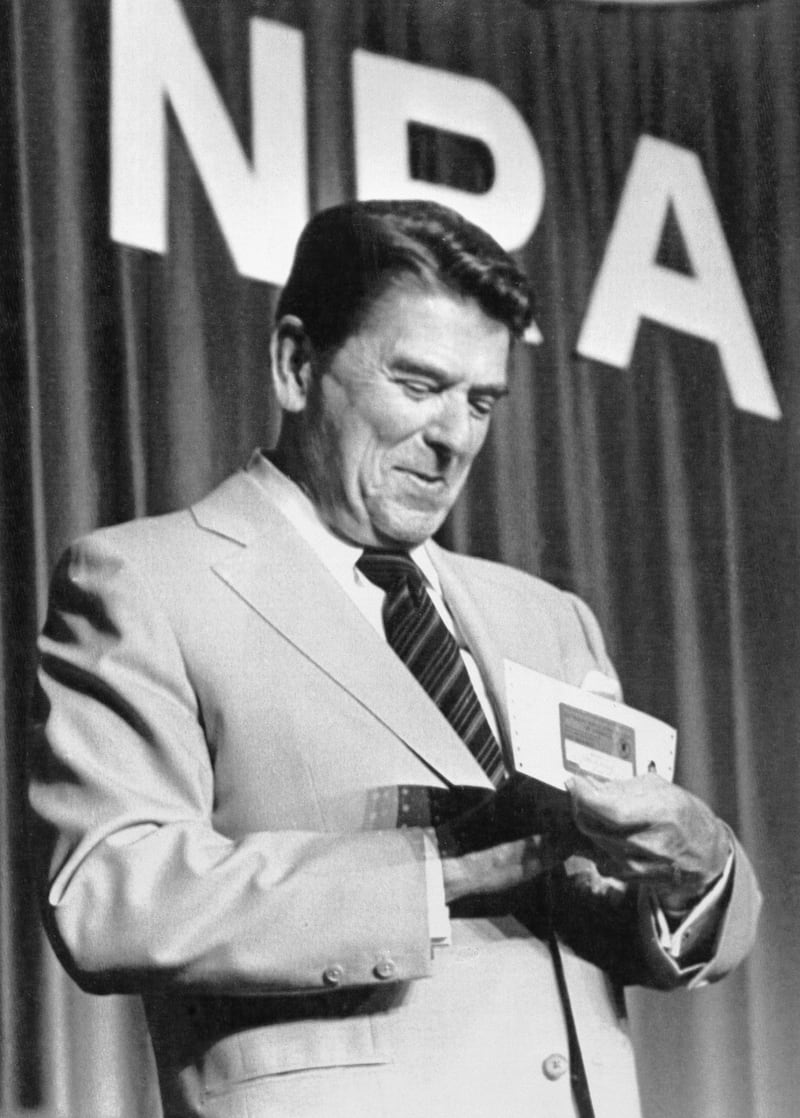

President Reagan looks with pride at his new life membership card for the National Rifle Association. Reagan was presented with his new card by NRA Vice President Harlon Carter after he addressed the group at the Civic Center here.

GettyBy 1985, when Carter retired, the NRA had surged from 1 million members in 1977 to 3 million members—with 3,000 new members joining weekly. The New York Times pronounced it “The most persistent and resourceful of all single-issue groups.” The activist Osha Gray Davidson writes: “To the NRA faithful, Harlon Carter is Moses, George Washington and John Wayne rolled into one.”

In 1981, reporters discovered that Carter had killed Ramon Casiano a half-century earlier in 1931, in Laredo, Texas. Three Mexicans hanging around had scared Carter’s mother. She suspected they had stolen the family car three weeks earlier. Carter, 17 at the time, took a shotgun, found the three, and confronted them. Casiano, who was 15, brandished a knife. It should have been a fleeting, post-pubescent, macho standoff. Instead, Carter shot—killing Casiano instantly. Despite claiming self-defense, Carter was found guilty of murder without malice aforethought and sentenced to three years in prison. A higher court voided the conviction, invalidating the judge’s explanation of the rules of self-defense. Although Carter denied it all when first exposed—he didn’t need to lie. The story enhanced his legend among the NRA’s couch-potato cowboys.

Last year, the Southern alternative rock band, Drive-By Truckers, sang about “Two boys with way more pride than sense / One would fall and one would prosper / Never forced to make amends.” The chorus of “Ramon Casiano” skewers Carter: “He had the makings of a leader / Of a certain kind of men / who need to feel the world’s against him / Out to get ’em if it can.”

In mounting the NRA’s n.r.a—new revolution against gun control—Harlon Carter pushed his fight to bear arms beyond the Second Amendment. He rode the broader backlash against the baby boomers’ liberal revolt. He also exploited the shift in American politics toward single-issue grandstanding that resonated in an increasingly shrill, zero-sum political culture, bankrolled by fat cats, and fueled by a grassroots fury politicians from Ronald Reagan through Donald Trump have tapped.

Carter’s crusade proves that America’s crime problem cannot be solved by simple sloganeering, left or right. “Guns kill people”—but “people kill people” too. And the people gripping their guns are trying to hold onto a much bigger identity package, making compromise on the issue itself—and any progress—that much harder to achieve.

Further Reading:

Osha Gray Davidson, Under Fire: The NRA and the Battle for Gun Control (1993, 1998)

Laura Smith, “The Man Responsible for the modern NRA killed a Hispanic Teenager, before becoming a border agent,” (2017)

Joel Achenbach, Scott Higham, and Sari Horwitz, “How NRA’s true believers converted marksmanship group into a mighty gun lobby,” The Washington Post, Jan. 12, 2013.