On Monday night, shortly after the Ferguson grand jury made its decision not to bring charges against police officer Darren Wilson for the death of Michael Brown, the prosecutor in the case released the evidence seen by the jury. While the evidence answers some fundamental questions surrounding Brown’s shooting, and the investigations and legal proceedings that followed, it leaves others unresolved.

The evidence considered by the jury hinged on a 90-second exchange of words, violence, and gunshots. No single picture of Wilson’s actions and Brown’s final moments emerges. Instead, the evidence provides several overlapping versions of the crucial moments; clear enough for the jury to make its decision but not without leaving traces of doubt.

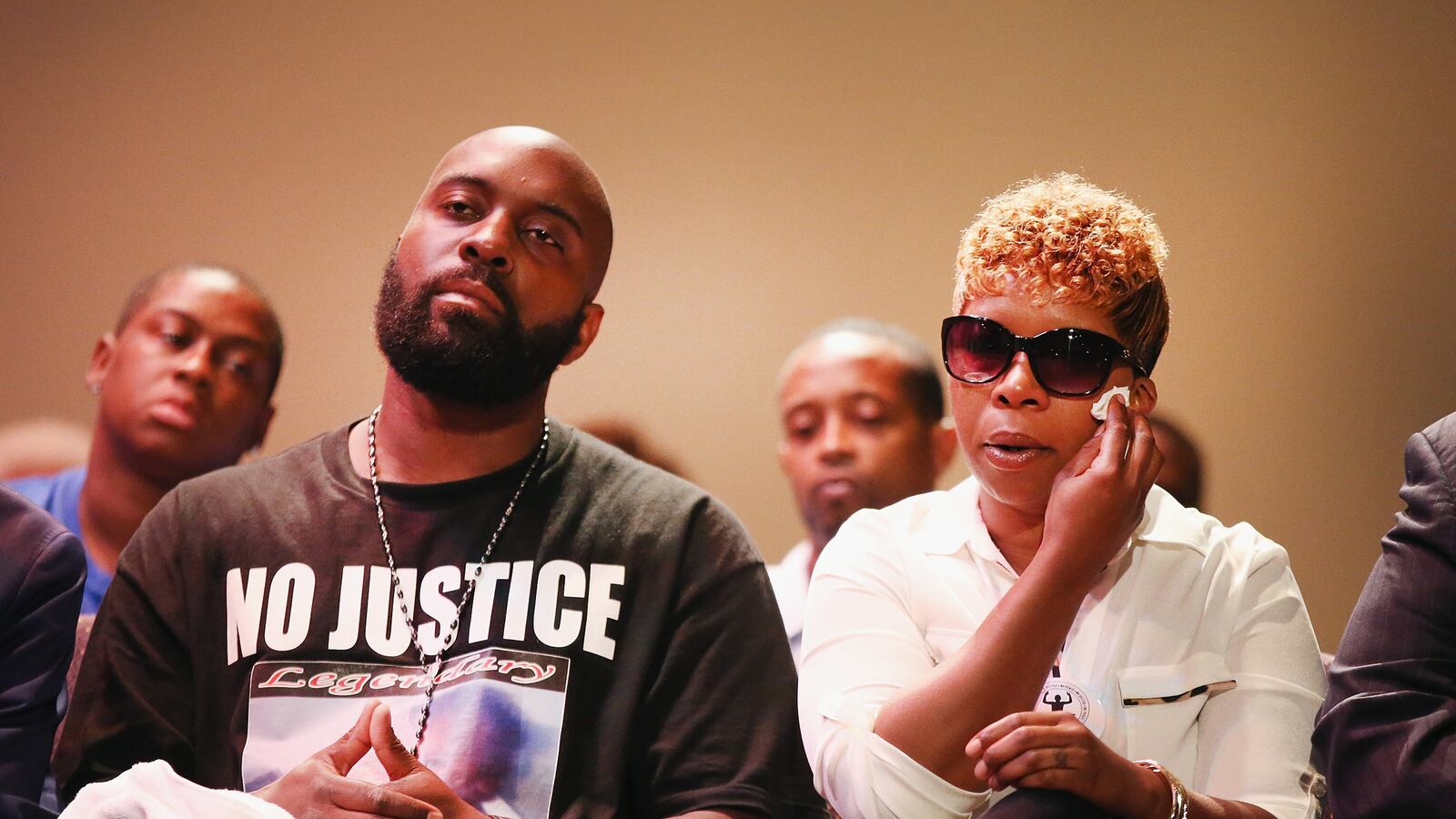

On the key question, whether Wilson committed a crime or believed he was defending his life when he shot Brown, the jury clearly sided with the officer. There is evidence in the thousands of pages of testimony, and evidence released supporting Wilson’s version of events. But for protesters in Ferguson and others who saw the case as a judgment, not only on Brown’s death but broader issues of racial injustice and police violence, there is evidence from eyewitnesses, and in the prosecutor’s handling of the case, to affirm their convictions and anger.

Here’s an incomplete list addressing some of the unanswered questions about the grand jury process and what comes next in Ferguson.

Could Darren Wilson face more legal trouble?

The lead prosecutor in the case, Robert McCulloch, said: “It is now a closed investigation,” after he announced the grand jury’s decision Monday night. That closes door on a criminal prosecution of Wilson, but both he and the Ferguson Police Department are subjects of a federal investigation led by the Department of Justice.

The DOJ case against Wilson focuses on whether he deliberately violated Brown’s civil rights. But the prospects for such a ruling appear slim, according to legal experts because, as Attorney General Eric Holder stated Monday night, “federal civil-rights law imposes a high legal bar in these types of cases.”

Apart from the federal investigation, Brown’s family could pursue civil damages against Wilson. In a civil case, the burden of proof is lower than in a federal case or criminal court, generally requiring only a “preponderance of evidence” to find Wilson guilty of wrongdoing.

Were there inconsistencies in the police accounts of Darren Wilson’s encounter with Michael Brown?

On the afternoon Brown was killed, he had stolen a pack of cigars from a convenience store. The crime was caught on tape and publicly released after the shooting, but official police accounts connecting the robbery and shooting have varied with the Ferguson police chief, at one point, contradicting Wilson’s own version of events.

In August, Ferguson Police Chief Thomas Jackson first said that Wilson knew Brown was a suspect in the robbery before the shooting. But in later interviews, Jackson appeared to change course, saying that Wilson had stopped Brown only for walking in the middle of the street, without mentioning the convenience-store theft.

In Wilson’s testimony to the grand jury, he said that his interaction with Brown and Brown’s friend Dorian Johnson, a witness to the shooting, began when he saw them walking in the middle of the street and told them to get on the sidewalk. It was after Brown refused, cursing at him and continuing to walk in the street, that Wilson said he made the connection.

“When I start looking at Brown, first thing I notice is his right hand, his hand is full of cigarillos. And that’s when it clicked for me because now I saw the cigarillos, I looked in my mirror, I did a double check that Johnson was wearing a black shirt, these are the two from the stealing.”

At that point, Wilson testified, he called for backup and reversed his own car to cut off Brown and Johnson’s path setting in motion the events the events that led to the shooting.

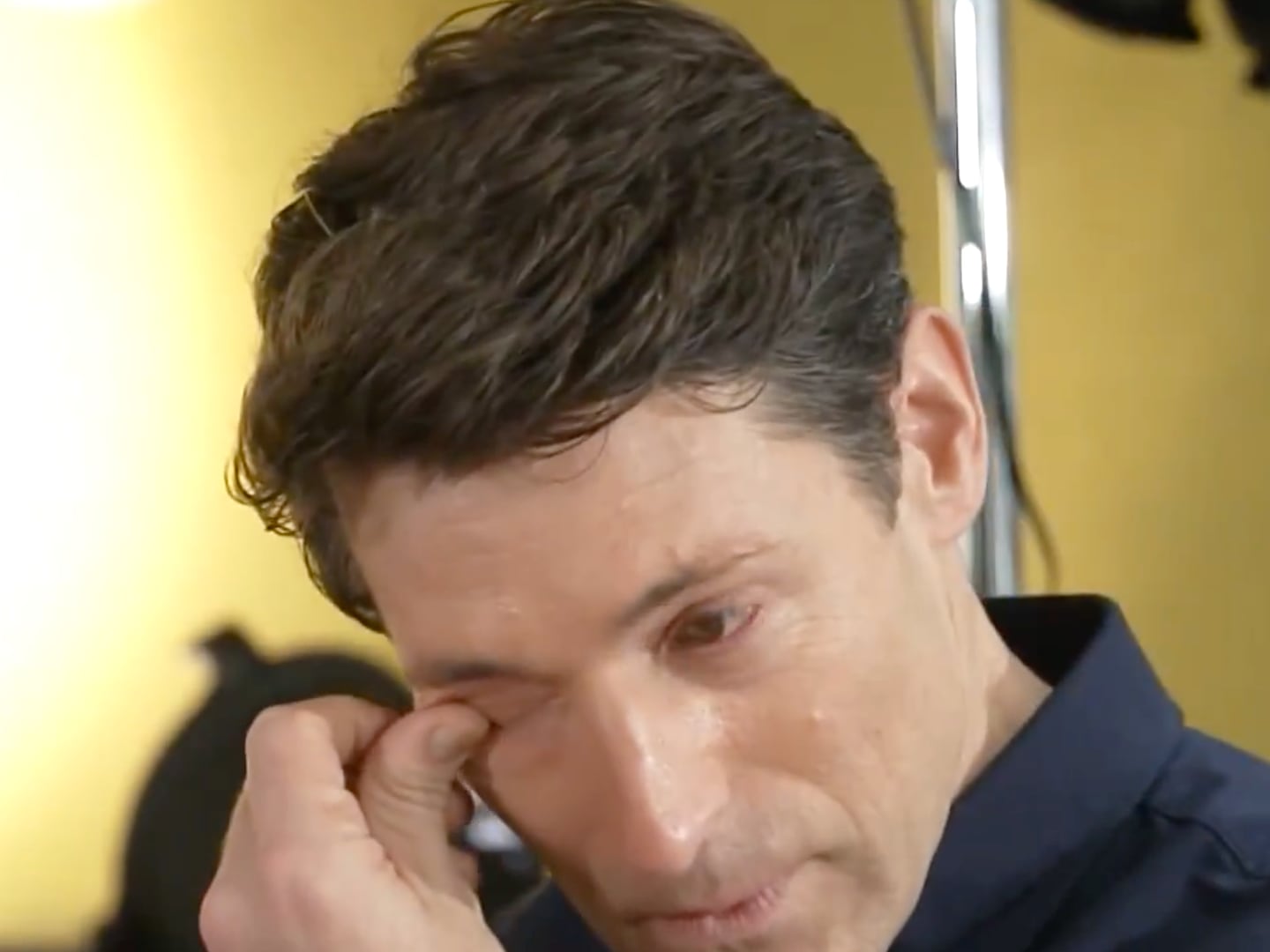

Was the prosecutor trying to avoid an indictment?

Starting in August, in the lead up to the grand jury, there were calls for St. Louis County Prosecutor Robert McCulloch to step aside. Critics alleged that McCulloch’s close relationship with the police department presented a conflict of interest. McCulloch has relatives on the police force, including his father—an officer who was killed in the line of duty when he was shot by a black man.

An online petition calling for McCulloch to recuse himself gathered 70,000 signatures, according to Jamilah Nasheed, the state senator who started it, but it failed to get the prosecutor removed from the case.

McCulloch’s connections to the police department notwithstanding, any prosecutor would have faced obstacles to an indictment, which are easy to secure in cases involving civilians but far harder when dealing with police officers.

Prosecutors typically don’t take a case to a grand jury unless they are confident they can get a conviction. The case against Wilson was never easy to make, given the special laws governing “justifiable homicides” in police shootings.

For jurors to have indicted Wilson on involuntary manslaughter, the least severe of the four charges available, they would have had to been shown that Wilson did not believe his life was in danger. Even if other evidence suggested that Wilson’s life was not actually in danger, as long as the officer could show that he had an “objectively reasonable belief” that Brown posed a mortal threat, his actions would be protected under Missouri’s guidelines for a justifiable homicide.

Faced with the high burden of proof surrounding a contested police shooting, what’s clear is that McCulloch did not aggressively push for a prosecution. Rather, the lead prosecutor took a series of steps that are unusual in a grand jury proceeding and that likely influenced the jury’s final decision. Rather than building a case intended to prove Wilson’s criminal culpability before the jury, McCulloch presented all the evidence in the case. In effect, the lead prosecutor gave equal weight to the prosecution and the defense. That’s technically in keeping with the prosecutor’s responsibility to “disclose any credible evidence of actual innocence,” but highly unusual, since prosecutors usually only appear before grand jurys in cases where they are convinced of a party’s guilt.

In this case, it appears that McCulloch was never convinced of Wilson’s guilt and, if not for the intense media attention and political pressure around the case, would never have taken it to a Grand Jury.