Since her HIV diagnosis 24 years ago, Laurie Ann Lewis can count on one hand the number of times she’s missed her quarterly appointment for blood work. Both were this spring.

For patients with the deadly virus that causes AIDS, regular blood draws are the only way to make sure their medication is keeping their viral loads in check. But as cases of another infectious disease, COVID-19, surged earlier this year, Lewis’s doctor told her to stop coming in. Labs had become overwhelmed with coronavirus testing. Blood work for patients with HIV would have to wait.

Living with a compromised immune system is frightening even in the best of times, Lewis, a 56-year-old mother of three in Jackson, Mississippi, explained. Now is not the best of times.

“I’m scared for my life,” Lewis told The Daily Beast. “I don’t know what my counts are, so I don’t know if I’m healthy enough to go anywhere. I can’t even see my children. I just sit in my house.”

Two hours up Highway 49, nurses at the Aaron E. Henry Community Health Centers, a network of federally-funded clinics in northwest Mississippi, normally test around 250 patients for HIV each month. Like many pockets of the South, HIV has embedded itself in this rural corner of the state, where (in some counties) close to 1 percent of the adult population lives with HIV, a rate three times the national average.

But in April and May, nurses at the clinic didn’t do a single HIV test. Instead, clinic CEO Aurelia Jones-Taylor said, all of Aaron E. Henry’s HIV resources—from testing to transportation and community outreach—shifted to coronavirus.

“We’ve put all of it on hold. Our focus during this time, even with our HIV patients, has been COVID,” Jones-Taylor said.

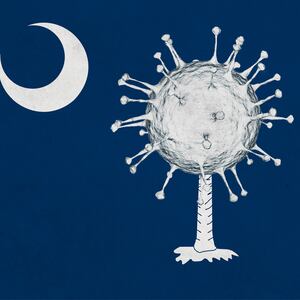

For months now, COVID-19 has altered health-care operations throughout the United States—preventing or complicating elective surgeries, scaring people away from visiting doctors for routine appointments, and encouraging at-home births. But when it comes to HIV and AIDS prevention in the Deep South, a uniquely vulnerable region both to AIDS and COVID-19, the coronavirus pandemic hasn’t just slowed down normal HIV prevention efforts—it’s derailed them. Both diseases disproportionately hurt communities of color, and in an overburdened health-care system, focusing on one could mean letting both run wild.

“HIV is still a crisis. And it’s a major crisis here in the South. But that’s pushed to the side, because we’re responding to the COVID crisis,” said Derick Wilson, executive director of the Southern AIDS Coalition.

What’s especially dangerous about this, Wilson said, is that COVID-19 is disproportionately affecting many of the same communities—especially Black ones—hit hardest by HIV and AIDS.

“If you were to look at a heat map of persons who are contracting COVID and dying from it and also HIV rates, it would look pretty much the same,” he said.

By early summer, operations at Aaron E. Henry began returning to normal. In the third week of June, nurses at the clinic tested three patients for HIV. But that same week, the infection rate for coronavirus surged throughout the Southeast, and few places more than in Mississippi, which saw new daily infections nearly triple in June for almost 30,000 total cases.

“A second wave is going to hurt us, and the wave is just getting bigger. Right now we’ve got a tsunami,” Jones-Taylor said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a statement to The Daily Beast saying the organization was concerned “that the decrease in the availability of testing and limited access to treatment and prevention services [for HIV] may result in more infections and poor health outcomes in the long run.”

Those directly involved in the care of HIV patients were more blunt.

“This is a powder keg,” said Deja Abdul-Haqq, the director of development at My Brother’s Keeper, a community based nonprofit working to reduce health disparities in Mississippi’s underserved populations. “HIV needs a void, a space, a lack of attention. That’s how we got here in the first place, not paying attention to HIV. What do you think is going to happen this time when we turn our back on it?”

“I’m literally afraid to check our numbers,” she added.

But even if Abdul-Haqq wanted to check if the infection rate has grown the last few months, she wouldn’t be able to. A spokesperson for Mississippi’s Department of Health told the Daily Beast they “haven’t had the manpower” since February to update their infectious disease report, a core function of public health departments that lists new infections of everything from HIV and tuberculosis to West Nile Virus.

The bitter irony for many of these health-care workers is that COVID-19 has forced them to turn their backs on HIV at the exact moment the federal government had finally invested more resources into an ongoing epidemic.

In the four decades since the first cases of HIV were documented in New York City and San Francisco, the epicenter of the disease has migrated from coastal cities to the Deep South. The 16 states that make up the South account for 51 percent of all new HIV infections, according to the CDC.

But within weeks of their receiving an infusion of new federal funds early this year, Congress sent 58 of the 60 organizations that had received those dollars another $90 million, this time through the CARES Act, the pandemic stimulus package. For recipients of both grants, the message was clear: focus on COVID-19.

“It was a mandate,” Jones-Taylor said. “Because the (CARES Act) funding came with certain benchmarks we had to hit.”

According to Dr. Laura Cheever, associate administrator for the HIV/AIDS Bureau at the Health Resources and Services Administration, the federal agency that distributed both the HIV epidemic and CARES Act funds to those providers, it’s a bit more complicated than that. She argued that CARES Act funding wasn’t meant to subvert HIV dollars—it was meant to enhance them, allowing providers to integrate COVID-19 care into HIV care.

“I did not think that the... CARES Act funding would have HIV take a backseat,” Cheever said.

The problem, according to Wilson, is that the public health system in the United States isn’t equipped to manage two public health crises at once. Even with more federal dollars, the infrastructure and manpower needed to handle two public health emergencies doesn’t exist.

“And so then you take an under-funded and under-resourced system and ask it to respond to another crisis, you’re going to have to ignore one of those crises,” Wilson said.

A good example of what this looks like is the Mississippi State Department of Health, which has seen its funding cut over 10 percent since 2017. Dr. Lucius Lampton, who sits on the state Board of Health, said nurses are primarily focused on contact tracing for coronavirus, despite the fact that those teams were created to track infectious diseases like tuberculosis and HIV. He said he wasn’t surprised that the agency hasn’t had the manpower to update its infectious disease statistics. Even the leadership, he said, is working multiple jobs.

“Dr. Dobbs has had to do clerical duties to keep the website up,” Lampton said, referring to the state health officer Thomas Dobbs. “He’s had to enter the data (on COVID) himself.”

“There’s no way you can say there's not a distraction from the core public health work,” he said.

Liz Sharlot, head of communications for Mississippi’s Department of Health, denied that the state’s top doctor was doing data entry, but admitted that Dobbs is “probably sleeping three hours a night. We’ve had our hands full.”

Still, Cheever of HRSA points out, providers of HIV care are infectious disease experts with years of experience in the communities they serve, traits that make them uniquely positioned to handle a public health crisis like the coronavirus at the local level.

And those on the front lines of HIV and COVID-19 admit there are similarities in the virus, both in how it’s transmitted and who it infects.

“It’s an interesting parallel, that both COVID and HIV are spread by the same human desires,” Wilson said. “They’re both spread by a human desire for connection, whether it’s sexual connection or it’s social, and that’s the common denominator for both of them. So we do have to consider that commonality in the way we approach the illness.”

Both viruses have disproportionately affected racial and ethnic minorities. Black Americans are hospitalized for coronavirus at five times the rate of white Americans. Likewise, even though Black Americans make up just 13 percent of the US population, they have 42 percent of new HIV infections.

And both HIV and COVID-19 began on the coasts, but seem to be doing some of their most long-term damage in the South, perhaps because state officials there have been reluctant to respond to either disease.

“I don’t think that this is a second wave in the South, I think this is a pattern that we’ve seen in HIV. HIV primarily started with epicenters in New York and northern California, and then they responded, and did the things they needed to do, and Southern states did not respond as vociferously. And then suddenly there was a shift, and then the South became the place that has the most HIV,” Wilson said.

“That’s the exact same thing that has happened with COVID,” he continued, adding, “The South is where we’re seeing the most cases now, all because leadership failed to pay attention to history.”

A spokesperson for Gov. Tate Reeves of Mississippi said the governor was alarmed by the rising rate of infections, but that he can’t control the behavior of Mississippians.

“As of right now, people are not following even the less restrictive rules. We are very concerned about the increase in numbers, and see it primarily as a sign of people giving up on the mission rather than easing up on the measures,” said Parker Briden, a deputy chief of staff for the governor.

Sean Kelly, associate medical director of the Vanderbilt Comprehensive Care Clinic, which is home to the Southeast AIDS Training and Education Center, said he’s tried to look for the silver lining. One of those, he said, is that COVID and the risk of infection posed by in-person treatment has greatly expanded how clinics use telemedicine, something that Kelly said he expects many of them will adapt to the treatment of HIV.

But as coronavirus infections surge across the country, and especially the Southeast, Jones-Taylor is concerned this may not happen for a long time.

“We feel confident that we’ll be able to ramp up the testing, to identify the patients who may need to be put on medication,” she said. “But you’re not going to make up for lost time. Time lost is time lost.”