On April 10, 1912, the Countess of Rothes boarded the Titanic and embarked on a voyage to America where she was to join her husband and share in his idyllic, if rather quixotic, dream of owning and operating a California orange grove.

At 33 years old, with a kindly expression and manner, and lucent dark eyes, the Countess was the Titanic’s most distinguished passenger, for among the ship’s renowned, moneyed travelers, only the Countess was renowned and moneyed—and titled.

She was accompanied by her maid, and three steamer trunks stocked with signifiers of privilege: custom-made beaded dresses, hand-stitched satin and lace lingerie, a gold and silver vanity set, a diamond belt buckle, tea hats with hand-dyed ostrich feathers.

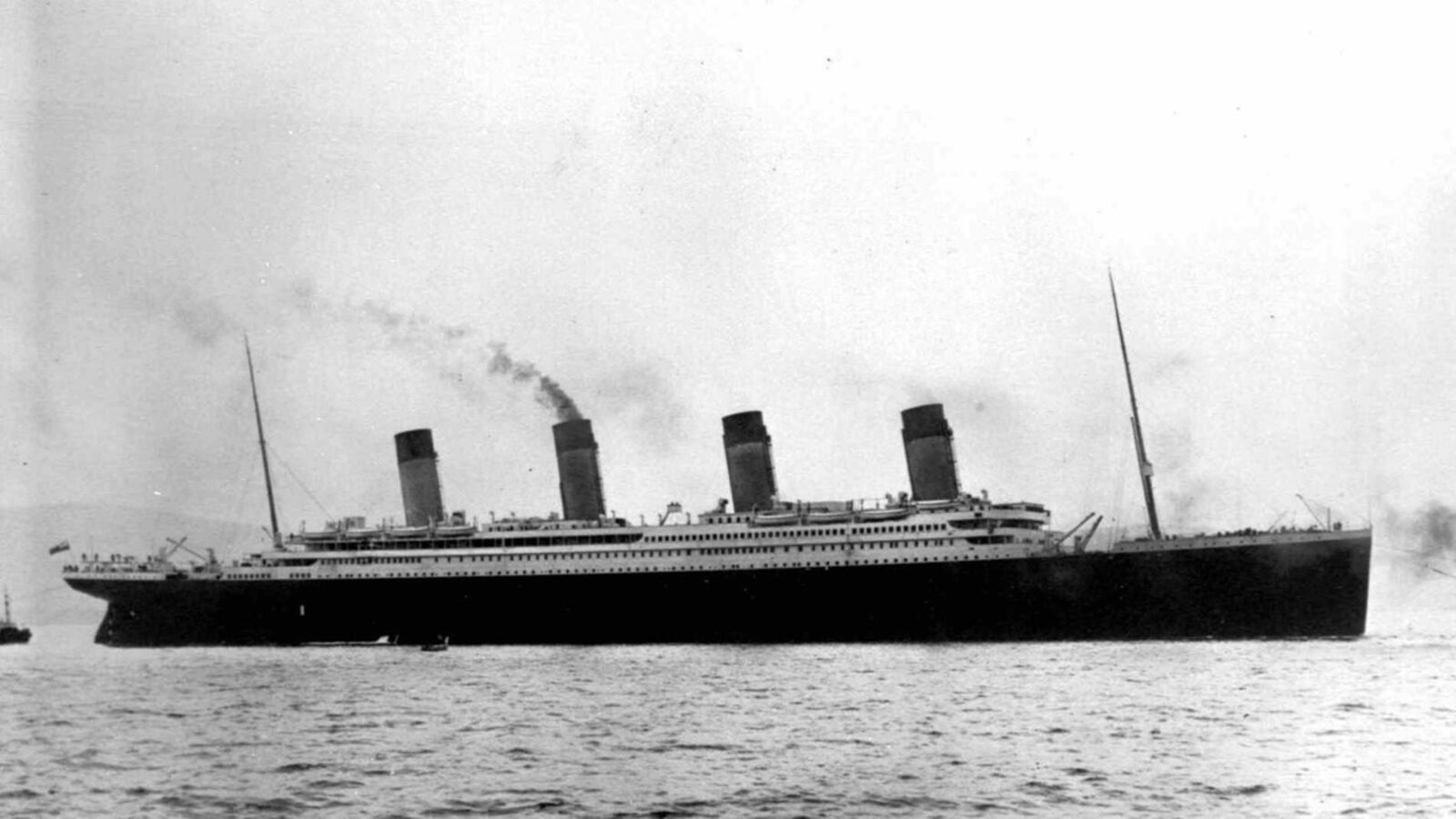

The four days at sea were unrelentingly posh and blessedly uneventful until the towering iceberg pierced the Titanic’s hull and divided the lives of everyone onboard into before and after.

At 1:10 a.m. on April 15, the Countess stood on the Titanic’s Boat Deck wearing a life belt, a full-length ermine coat, and an heirloom necklace configured from 300-year-old pearls. Capt. Edward Smith took her gloved hand, and guided her into Lifeboat No. 8, a wooden, white-painted craft measuring 30 feet long and nine feet wide. Moments later, the lifeboat was lowered 65 feet into the frigid ocean which, on that star-filled, moonless night, was as smooth and unmoving as glass.

Lifeboat No. 8 was built to hold 65 passengers, but as it landed in the water, it carried one steward, two sailors, Able Seaman Thomas Jones, and 23 women who had been traveling in first class and were variously clad in nightgowns, evening gowns, fur coats, high-button shoes and white satin slippers. Mere hours had passed since these ladies had nibbled on after-dinner chocolates and petitfours, and sought refuge from the bitter night air beneath the plump eiderdown quilts that covered their gilded Queen Anne and Louis XV beds. Yet now, they were afloat in the forbidding sea, staring up at the grandest and mightiest ship ever made and moving away from her because she was sinking.

Above all things, the Countess thought, we must not lose our self-control. But some of the women were soon quarreling about not having enough room to sit down; the Countess calmed them, speaking in a quiet, determined manner that impressed Seaman Jones.

The two sailors had secured their seats on the lifeboat by assuring Captain Smith that they knew how to row but in fact, astonishingly, they didn’t. Their ineptitude required the seaman to abandon his post at the tiller and man an oar himself.

“Would you care to have me take the tiller?” the Countess asked.

“Certainly, lady,” Jones said.

With three other men on board, this was an unusual concession: British women were meant to be wives, mothers, and decorative, in that order. And yet, Seaman Jones thought of the delicate Countess, she is more of a man than any we have on board.

The Countess deftly steered the lifeboat, a resolute and unlikely vision in her ermine and pearls.

As the other women in Lifeboat No. 8 took up oars, Maria Peñasco, a 22-year-old bride, screamed for her husband who, like most of the other men, had gallantly heeded the call “women and children first” and remained aboard the Titanic when she vanished into the ocean. The Countess sat down beside Maria and held her. Poor woman, she thought her sobs are unspeakable in their sadness.

Then came other screams, the horrifying screams of more than a thousand women and men, struggling and adrift in the subfreezing water. The Countess held Maria tighter, seeking, in vain, to keep her from hearing those agonized cries until, finally, they were replaced by a deathly, accusatory silence.

In its wake, the Countess was overwhelmed by a feeling she could identify only as “indescribable loneliness.”

“Let us row back!” one of the passengers in the lifeboat implored, “and see if there is some chance of rescuing anyone who has possibly survived.”

The Countess, an American lady, and Seaman Jones agreed. But everyone else in Lifeboat No. 8 was adamant that no good could come from steering so small a craft into a disaster field where hundreds upon hundreds were dead or dying.

Reluctantly, those who wished to return to the site of the sinking yielded to the majority, against their will, their faith, and their better judgment. The ghastliness of our feelings, thought the Countess, never can be told.

Throughout the night, the Countess rowed, and when the women on Lifeboat No. 8 sought to keep up their spirits by singing, her clear soprano was heard above the others as her favorite hymn was sung:

Lead, kindly light, amid the encircling gloom…The night is dark, and I’m far from home, Lead Thou me on!

At last dawn came, a heart-moving sight that filled the canvas of the cloudless sky with giant brush strokes of pink and gold and tangerine. In the early light, the Titanic’s survivors were picked up by the ocean liner Carpathia and, when safely onboard, the Countess managed her own bottomless sorrow by tending to the sick, making clothes for bereft children, and comforting the grieving. By the end of the first day on the Carpathia, the ship’s crew had dubbed her “the plucky little Countess.”

“You have made yourself famous by rowing the boat,” a steward told her.

“I hope not,” the Countess said, “I have done nothing.”