Can the victims of hate crimes, or their families, ever see justice under our system?

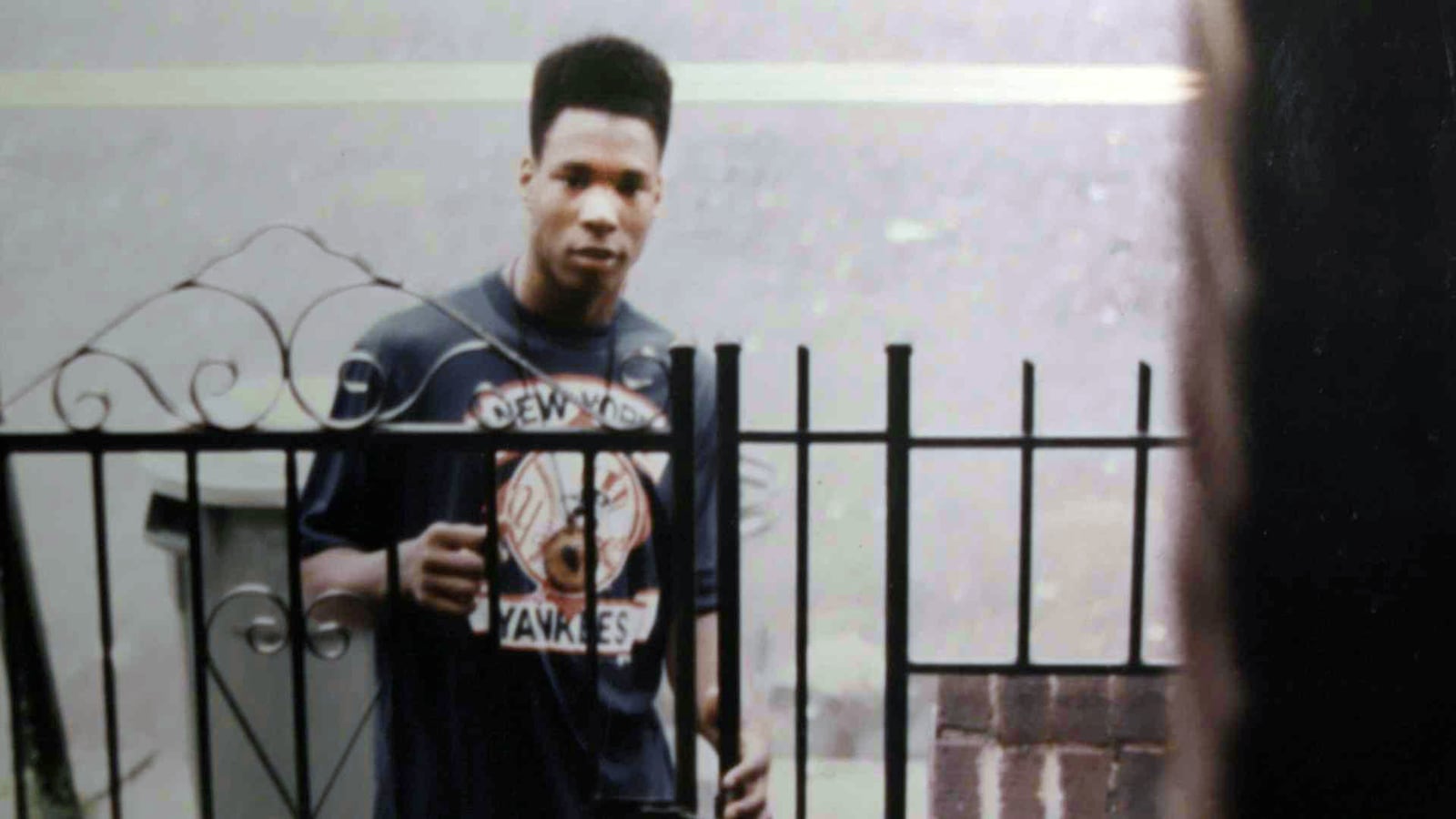

Muta’Ali’s latest documentary Yusuf Hawkins: Storm Over Brooklyn, which aired on HBO Wednesday, tells a complex tale of violent racism and carceral logic. Yusuf, a Black teenager, middle child of three boys, and role model to his friends, was 16 years old when he was shot twice and killed in 1989 Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, a predominantly white Italian neighborhood. There was, as it’s repeated throughout the film, no good reason for the attack against Yusuf—in fact, a racist mythology swirled around the neighborhood involving a local girl and her rumored Black boyfriend.

Yusuf was in the neighborhood with his three friends to look at a used car, and didn’t know this girl or the 30-plus white boys who surrounded him. These boys and the neighborhood that raised them would deny responsibility for Yusuf’s death, let alone having racist beliefs (archival footage and audio shows several of those involved, as well as various Bensonhurst residents, casually referring to Black people as “n****rs”). Storm Over Brooklyn hears them out, but ultimately argues that racism doesn’t just materialize in instances—it is a scourge to the entire spirit of a place.

Muta’Ali interviews the young man, Joseph Fama—now middle-aged–who was sentenced to 32 and a half years for Yusuf’s murder, from prison; Fama claims he’s innocent. He says he was a mere bystander who fled town right after the shooting because he was spooked, not because he did it. It’s difficult to make sense of this denial, because the film doesn’t present any of the evidence from the case or conduct its own investigation. Instead, we hear from the white police officers and detectives who investigated, including one who admits to bringing up prison rape to Keith Mondello, who was also charged in Yusuf’s murder as the accomplice who organized the white teenage mob. Everyone interviewed, including Mondello’s own lawyer, admits that the attack was at the very least “racially motivated”—a common euphemism for racist—but in 1989, the story amongst Bensonhurst residents was that Yusuf was just in the wrong place at the wrong time; a tragedy occurred, and Black people had better get over it.

It’s this insult to good sense that drives the actions of Yusuf’s father, Moses Hawkins, who was absent during most of his childhood, but had returned eight months before Yusuf’s death to renew his commitment to fatherhood. Moses blazes fiercely toward a carceral justice, while Yusuf’s mother, Diane, tries and fails to grieve properly. Moses encourages her to show strength and not vulnerability; in both interviews and archival video footage, her pain tears through. Al Sharpton guides the parents and their living sons, Amir and Freddy, through marches and appeals to justice as New York’s first Black mayor, David Dinkins, is campaigning and eventually elected. Here, the film struggles to make sense of the differences between Black political figures, from Sharpton to Dinkins to Jesse Jackson to Martin Luther King, Jr. to notorious anti-Semite and eventual Malcolm X foe Louis Farrakhan, who Moses invited to speak at Yusuf’s funeral. Instead, we’re simply served with an idealistic slate of varying ideologies and approaches without a strong sense of their contexts or failings.

In the midst of these narratives, Diane’s story, as well as Yusuf’s friend and witness to his murder, Luther Sylvester, get lost. These two people bear unique traumas because Yusuf’s death nearly annihilated them—justice was not top of mind; they wanted to lay their flowers, in their way. Sharpton’s machinations—savvy, opportunistic, or some mix of both—are the center of Muta’Ali’s depiction, but the story that often doesn’t get told is how the pain of racism cannot only be addressed with righteous indignation. Surely, Black people marching over Yusuf’s death—taking over the streets of Bensonhurst while risking retaliation by angry white people—was a vital challenge to the status quo that demanded (and still demands) that oppression be kept quiet for so-called peace to prevail. But that is the familiar story, and the one that is apparent now. What we don’t address enough in the conversation about racial justice is the trail of trauma left in the wake. There are no chants for this, and what Mayor Dinkins offered, a promise of healing and reconciliation, cannot be manifested by an election cycle.

After Yusuf’s death, Diane, like Eric Garner’s widow Esaw, was afraid to leave the house alone. When he returned to school after the killing, Luther Sylvester was unable to accept the help offered to him by his principal and guidance counselor. For years, he said, he thought it should’ve been him killed, and not Yusuf. Their crises were not purely individual or mental, but generational, communal, spiritual, and yes, political. The poison of racism affects everyone, even those who would seem to benefit from it. Russell Gibbons, a Black Bensonhurst resident, was aloof and tokenized yet still part of the otherwise white mob that surrounded Yusuf and his friends. Amir tells Ali that during the march, he saw white children all worked up, hurling epithets at him and the other demonstrators. “You’re not born with that,” he points out, “that’s something you learn.” You also learn fear and how to push down painful emotions and paper over them with the image of strength. You learn to draw up enemies in your head and pursue them in the street.

Now, in 2020, there’s an emphasis on “unlearning” racism or becoming “anti-racist,” but that’s been met by a pushback against what critics deem an individual—rather than structural—understanding of racism. Instead of trying to navel gaze one’s way out of a racist society, the argument goes, one has to actually take to the streets and fight against it. Of course, from whatever angle you look at it, no one set of ideas will determine the tide of agitation; the civil rights movement was an amalgam of different thinking and approaches, and in fact, plenty of people of all races didn’t want to have a thing to do with any of it—at least not on the ground. It’s a touchy issue to try to speak to any shared project amongst Americans, let alone New Yorkers, because we live in a country that is still, after all this time, torn up by seemingly endless distortions—and so many refuse to admit or even see it. It’s clear, however, that in the case of Yusuf, and the many who came before and after him, acknowledgement is the vital first step.