This month Trump decided to resume his mass rallies starting in Tulsa, less than a mile from the site of the infamous 1919 race massacre there—and originally scheduled it for Juneteenth. The venue is an enclosed arena, although the spike in COVID cases there raised questions about his motivations. We know he misses the energy of his crowds, and that Oklahoma is one of the reddest states in the union. But there’s another strategic reason for propelling the rallies forward.

Trump needs them to propel the “juggernaut” 2020 Trump mobile app that campaign manager Brad Parscale has boasted about, that uses a service called geofencing to send messages to smartphone users in a given location, then track their locations and access their address books.

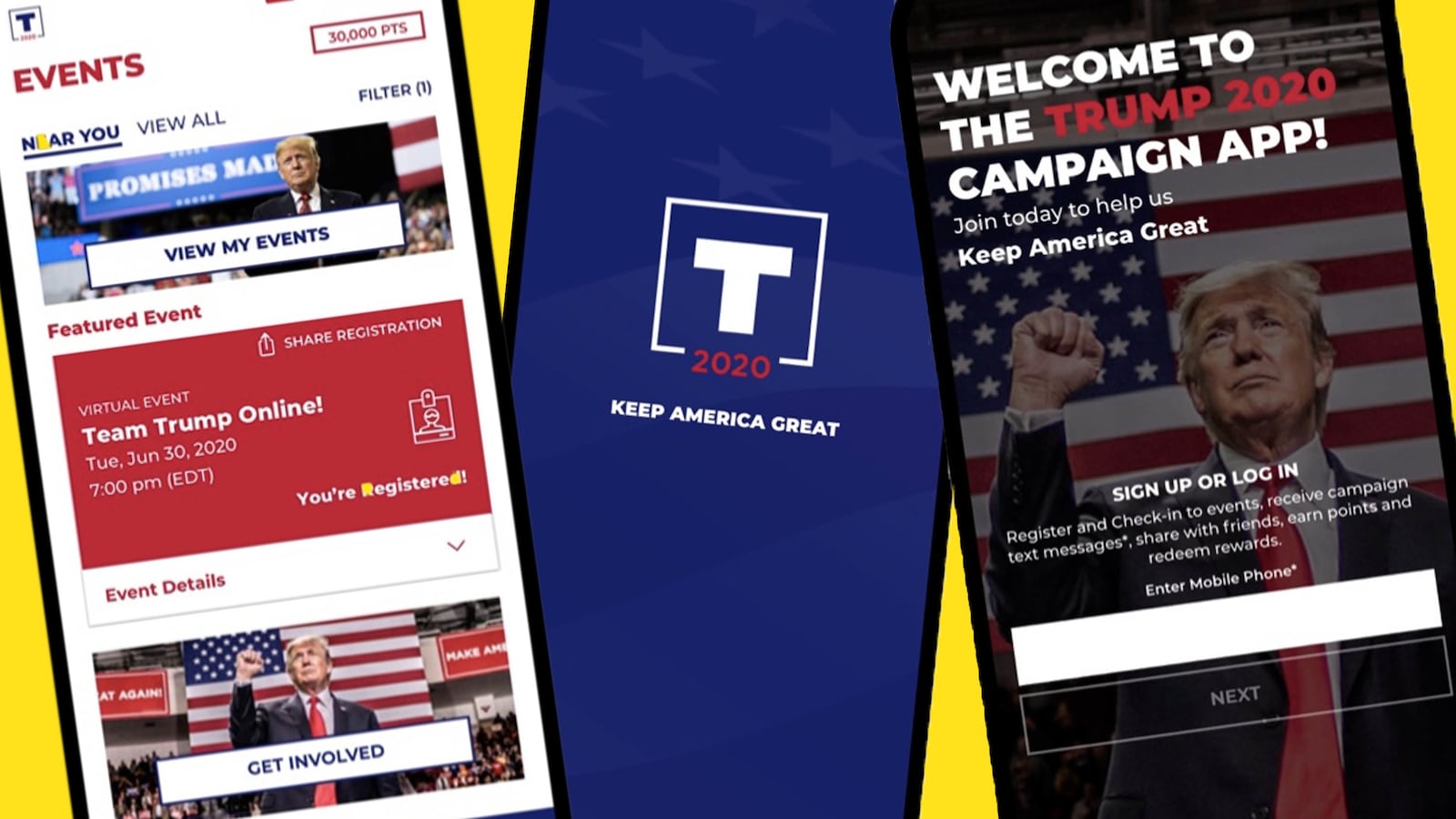

The plan is to harness the enthusiasm of the rally to get thousands of attendees to download the app, which requires them to enter their phone numbers and zip codes, and urges them to provide their email and home addresses as well. Parscale explained to CNN that once this information is provided, the campaign can combine it with the voter file from the Republican National Committee. This enhances the campaign’s ability to microtarget voters—that is, engage them on multiple communications platforms with tailored messages based on their specific concerns.

The app also uses gamification features, which award points that can be converted into prizes for additional actions like recruiting users’ friends and family members by messaging a user's contacts with invitations to download the app and join the campaign. Every contact’s download wins 100 points for the initiator. Five thousand points can be redeemed for a campaign store discount; 100,000 wins a photo op with Trump. The app also integrates pro-Trump news feeds from his favored outlets, such as Fox News and One America News, as well as the “news programs” presented by his daughter-in-law Lara Trump and son Donald Jr. Multiple actions can be carried out within the app, including making campaign contributions and sharing content with friends on Facebook and Twitter.

As The Daily Beast’s Will Sommer aptly described it, the app is built like a casino, but instead of one constructed to keep gamblers at slot machines this one is “trapping people inside an ecosystem of dangerous misinformation, conspiracy theories, and grievance politics. And it’s doing so while making the experience as fun and exciting as possible.”

Unfortunately for Parscale, Trump’s campaign rallies were suspended after the March 2 event in Charlotte, North Carolina, due to the COVID-19 outbreak. Parscale scrambled to adapt the app for virtual events, but the critical geofencing feature was neutralized. That appears to be one reason that Trump and his supporters have launched a full-court press to reopen the country to rallies and other large gatherings, including church services, despite the rising numbers of COVID-19 cases.

Parscale soft-launched the Trump 2020 app on April 23, but the big push didn’t come until June, in advance of the Tulsa rally. On June 3, Fox Business reported that the app had soared from number 1075 to number 323 in the App Store, and had been downloaded more than 385,000 times over the previous month—ranking 13th in the “news” category, just behind CNN and Fox. (Many other campaign apps, including “Team Joe,” classify themselves as “social networking” apps.)

Trump announced the Tulsa rally on June 10, and over the following week the Trump campaign registered supporters on multiple platforms. Some observers were puzzled at Parscale’s June 15 tweet claiming that the campaign had filled a million requests for tickets to Tulsa’s 20,000-seat venue, in a state with a total population of 4 million. Tellingly, the form required cellphone numbers, email addresses, and zip codes, making it a highly profitable data-harvesting operation.

Parscale’s app builds on innovations from a previous generation of Trump apps, initially created for Ted Cruz with the help of Cambridge Analytica and, separately, a developer called uCampaign. The uCampaign app pivoted to Trump after he won the primaries, and later built out a family of similar apps for the National Rifle Association, the anti-abortion Susan B. Anthony List, the Family Research Council, and other organizations run by members of the shadowy association called the Council for National Policy.

The Family Research Council promoted its app through its “ministry,” Watchmen on the Wall, which claims 70,000 member pastors across the country, who in turn promote the app and voter guides to their congregations. The Family Research Council, in turn, belonged to a consortium called United in Purpose, which had been engaged in data-mining evangelical populations for years. Some of these operations worked with the Koch-backed i360 data platform, which in turn shared data with the Republican National Committee’s Data Trust. It’s not hard to imagine the firepower of integrating data from other sources into the Trump 2020 apps.

From 2015 on, the uCampaign apps pioneered the use of gamification for political engagement. ThinkProgress reported that Bannon-related groups had also experimented with geofencing for conservative church congregations.

The Trump campaign dropped its uCampaign app, and a few months ago the NRA and the Susan B. Anthony List discontinued their apps as well. To develop the new Trump 2020 app, Parscale turned to the Austin-based company Phunware, which specializes in location-based services, i.e. geofencing. (Cambridge Analytica alumna Brittany Kaiser serves on its advisory board.)

The Trump campaign has established a decided advantage on the digital front; for example, @realDonaldTrump has over 82 million Twitter followers compared to @JoeBiden’s 6 million. The Democrats took an early lead in digital campaign tools with the Obama campaign in 2008 and the Democratic National Committee possesses a formidable database, but its operations are less effectively networked across state campaigns and into grassroots operations than the Republicans’. On the mobile front, the new Team Joe app shares some characteristics with Trump’s, including a request to access contacts and organizing tools.

But the Trump 2020 app is unusual in several respects, some of which lie embedded in its 23-page Terms of Service. “It’s even more abstruse than normal,” says technologist Steve Ross, editor-in-chief of Broadband Communities magazine. “There are a couple of things that stand out: First of all, its tracking, and second of all, it wants all your contacts. That was the original issue with Cambridge Analytica: you were giving up your contacts’ privacy, and Facebook thought that was perfectly fine.” (Ross adds that many apps ask users for their contacts, but typically state that they will use the contacts only to facilitate ease of use, not to send independent messages to the contacts.)

Another unusual feature is the “opt-out” feature involving permissions. Read carefully, the Trump app states that the app can use a signal like “Bluetooth” and “other similar” local connectors to identify the user’s location; the only way to opt out of the function is to “turn off Bluetooth and location services completely on the phone.” Ross adds, “The industry practice is normally opt-in. That’s not a legal requirement, but it’s far more ethical and desirable to have opt-in than opt-out.”

Parscale’s app urges the user to bypass both the professional news media and the social media companies that have begun to fact-check the president. “This allows every person who wants to support President Trump to directly download the app, get information, communicate with us without the need of a third-party company that might or might not be biased against us,” Parscale told CNN in April. As Trump pursues his vendettas against professional news organizations and Big Tech platforms, the appeal of the app’s discrete and direct communications sphere will only grow.

The Tulsa rally will serve as the Trump 2020 app’s coming out party, but its future is unclear. A few days after its June 11 update, the App Store was flooded with thousands of negative reviews from users complaining about an onslaught of spam calls, robocalls and texts, as well as glitches that came with the download. Some of these comments likely came from anti-Trump infiltrators, but others appear to be written by genuine Trump supporters who find the features intrusive and annoying.

“I would give it 0 stars if I could, “ one user wrote. “A soon as I opened the app my phone started glitching and when I gave it my phone number I constantly got notifications and texts from random people, while I was at a FUNERAL. No matter what I did they wouldn’t stop.” Another user wrote, “Now my phone is all glitchy. I will be uninstalling and never installing it again. Shameful this has the president’s name on it.”

Given the glitches, the spam, and the app’s terms of service, Ross notes that “it is quite possible that members of the campaign staff are actually selling user data in real time. Another explanation could be that there is computer code in this app that is spying on other apps, especially apps that haven’t been updated in a while. In rural areas that’s very common because the amount of data they can download is capped.”

It remains to be seen what the impact of the app will be on the ticketholders for Tulsa and subsequent rallies—but Brad Parscale’s job may well depend on it.