Last week, Hurricane Matthew was a Category 5 storm. In 2008, some described the financial meltdown as a Category 5 economic storm. How did “5” come to stand for devastating?

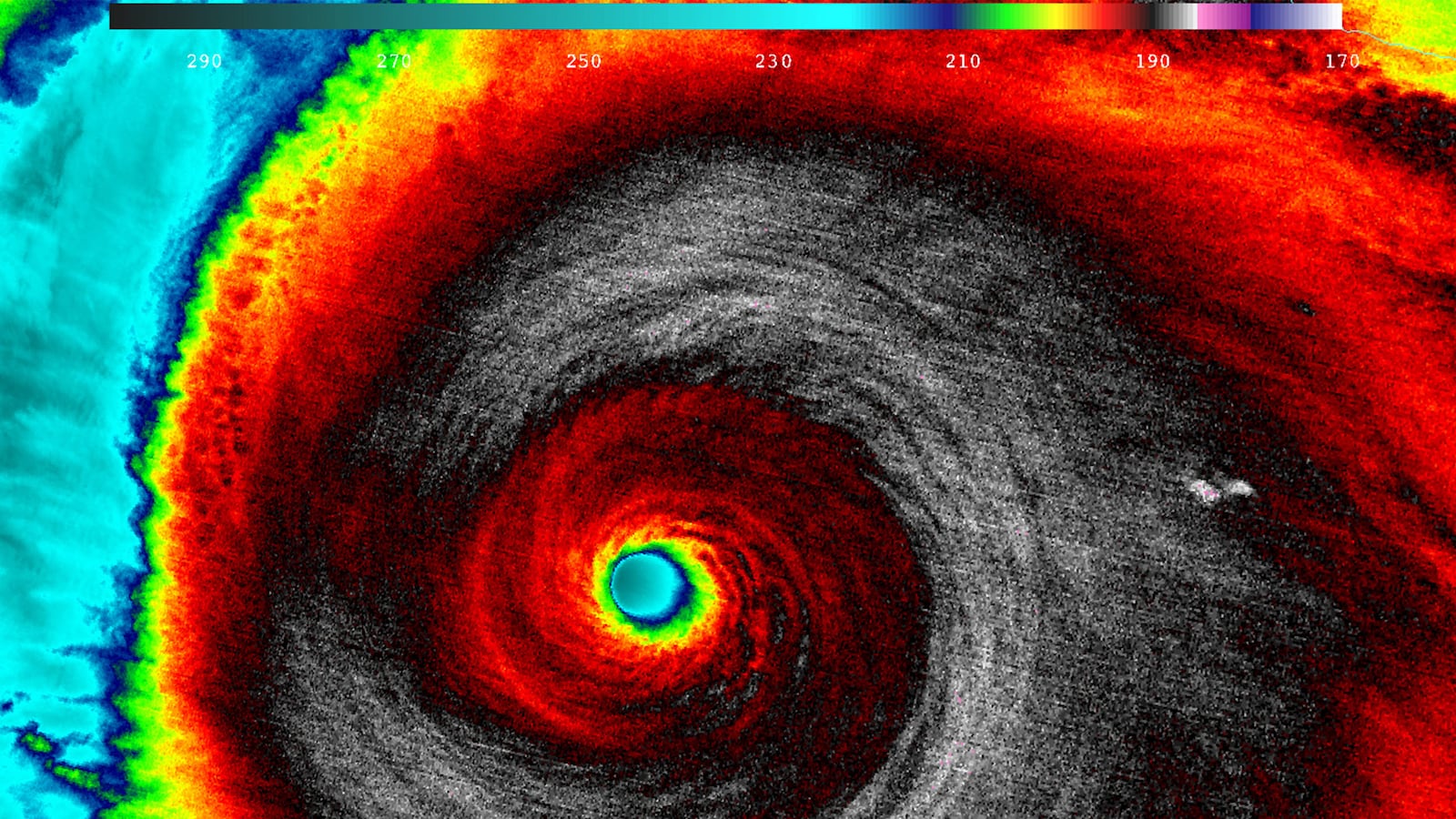

On one level, this story of the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale—that terrifying or reassuring gage predicting whether a hurricane will cause some damage—Category 1—or probably destroy your home—Category 5—is a technological tale. It’s about data collected by Geostationary (GOES) satellites, U.S. Air Force and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration hurricane reconnaissance aircraft, ships, buoys, and radar processed to offer a one-minute average that is roughly logarithmic in wind speed, with the top wind speed expressed as 83x10^(c/15) miles per hour rounded to the nearest multiple of 5. But the Saffir-Simpson scale is also a story of two experts who themselves survived catastrophes before collaborating on this now ubiquitous measurement.

When Robert Homer Simpson was 6 years old, he survived the Corpus Christi, Texas, hurricane of 1919—but one relative and 770 other people did not. Disaster struck during Sunday dinner. “Not only was there vast wreckage everywhere but houses, still intact, were afloat, many with refugees clinging to them,” he would recall. Perched on the sixth floor of the local courthouse, Simpson saw a man drown trying to save his baby.

Simpson realized that had the storm hit on Friday instead of Sunday, he and his friends would have died, because their school was destroyed. No one needs training in psychology to know when this meteorologist’s obsession with weather began. “What a dreadful experience to be thrust on a 6½-year-old lad,” he later said.

Hired by the United States Weather Bureau in 1940, Simpson forecast hurricanes in Miami during World War II and first flew into a tropical cyclone while establishing the Army Air Force weather school in Panama. After Simpson flew into Hurricane Edna with Edward R. Murrow in 1954, the legendary CBS reporter would say: “In the eye of a hurricane, you… feel the puniness of man and his works. If a true definition of humility is ever written, it might well be written in the eye of a hurricane.”

In 1949, Simpson started the weather station on the massive Hawaiian volcano Mauna Loa, ultimately heading the National Hurricane Research Project in 1955. Someone who blurred work and play, in 1965, he married his third wife, Joanne Malkus, a prominent meteorologist and had her replace him running Project Stormfury, an initiative to weaken tropical cyclones by seeding them with silver iodide. He became director of operations of the Weather Bureau, then director of the National Hurricane Center in 1968.

Back then, experts described hurricanes crudely as “major” or “minor.” Simpson sought a better tool, similar to the Richter Scale assessing earthquakes developed in 1935. Simpson understood that conveying information to the public effectively, efficiently, could mean the life-or-death difference between someone evacuating or hunkering down. “And that’s very difficult,” he would say; “a scientist trying to communicate with a person who is a non-scientist on a technical problem is very difficult…”

In 1968, Simpson began brainstorming with a structural engineer named Herbert Saffir. As a 17-year-old, the Brooklyn-born Saffir survived the sinking of the SS Morro Castle off the New Jersey coast on Sept. 8, 1934. That disaster—which occurred amid a perfect storm of a captain’s death, crewmembers’ incompetence, and safety procedures ignored, during a punishing nor’easter—killed 137 people. Saffir was one of only 85 survivors, mostly crew members, even though there was room for 408 people on the 12 lifeboats launched that nightmarish night.

In 1969, the United Nations commissioned Saffir to create a hurricane-preparedness model for low-cost houses in hurricane zones. As an engineer obsessive about building codes and safety who had lived in the coastal Florida hurricane region since the 1940s, Saffir was well-qualified. His breakthrough: devising a simple 1 to 5 scale based on wind speeds in 15 to 20 mph increments from 75 to 155, recognizing that once a hurricane hits 157 mph, no added categories were necessary, the effects were devastating enough. Simpson appreciated and implemented Saffir’s insight. “I just threw it in at the end of the report,” Saffir later explained. “I didn’t think much of it.”

Simpson added assessments of storm surges and flooding—data points eliminated by 2009—and started using it. In 1971, the scale helped warn residents to flee Hurricane Camille, which nevertheless killed 250 people and caused at least $1.4 billion in damage. President Richard Nixon dispatched Vice President Spiro Agnew to inspect the damage. While touring with the vice president, Simpson feared he overstepped when he told Agnew that without better airplanes the forecasting would be useless, no matter how effective the scale was.

But Simpson was a hero whose early warnings had saved thousands. Agnew’s report led to an upgrade of Hurricane Hunter Squadrons. And Richard Nixon, understanding the media’s nationalizing role, emphasized the “interest we have… shown” from “all the departments of Government, all the agencies in Government.” As Dr. Tevi Troy (my brother) reports in his new book, Shall We Wake The President: Two Centuries of Disaster Management from the Oval Office, Nixon’s concern about “the inability of forecasters to predict dangerous weather patterns” helped popularize the “familiar storm rating system.” After Camille, “the concept of a limited federal disaster response was no longer operable.”

Simpson retired from the National Hurricane Center in 1974, but continued consulting until shortly before his death two years ago, at the age of 102. Similarly, Saffir, who also designed 50 bridges during his career, worked until shortly before his death at 90 in 2007. Both remained modest about their now world-famous scale, although Saffir’s wife and sister occasionally grumbled when reporters forgot to call the category system the Saffir-Simpson scale.

“Before Camille, I think most people were thinking of a hurricane as a sort of local event,” Saffir would say. Now, these events are not only national tragedies but political tests. Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans—and derailed George W. Bush’s presidency. Sandy, the Northeastern storm, helped Barack Obama surge to re-election in 2012. This year, as Hurricane Matthew loomed, reporters speculated about the potential political fallout. We can concluded that presidencies, as well as countless lives, were saved, thanks to the simple scale devised by Robert Simpson and Herbert Saffir—two masters of disaster whose expertise helped them channel early traumas into heroic good works.