On Tuesday, Egypt's state news service announced that former President Hosni Mubarak had died in a military hospital in Cairo at the age of 91. This article is adapted from his political obituary published by The Daily Beast and Newsweek on Feb. 11, 2011.

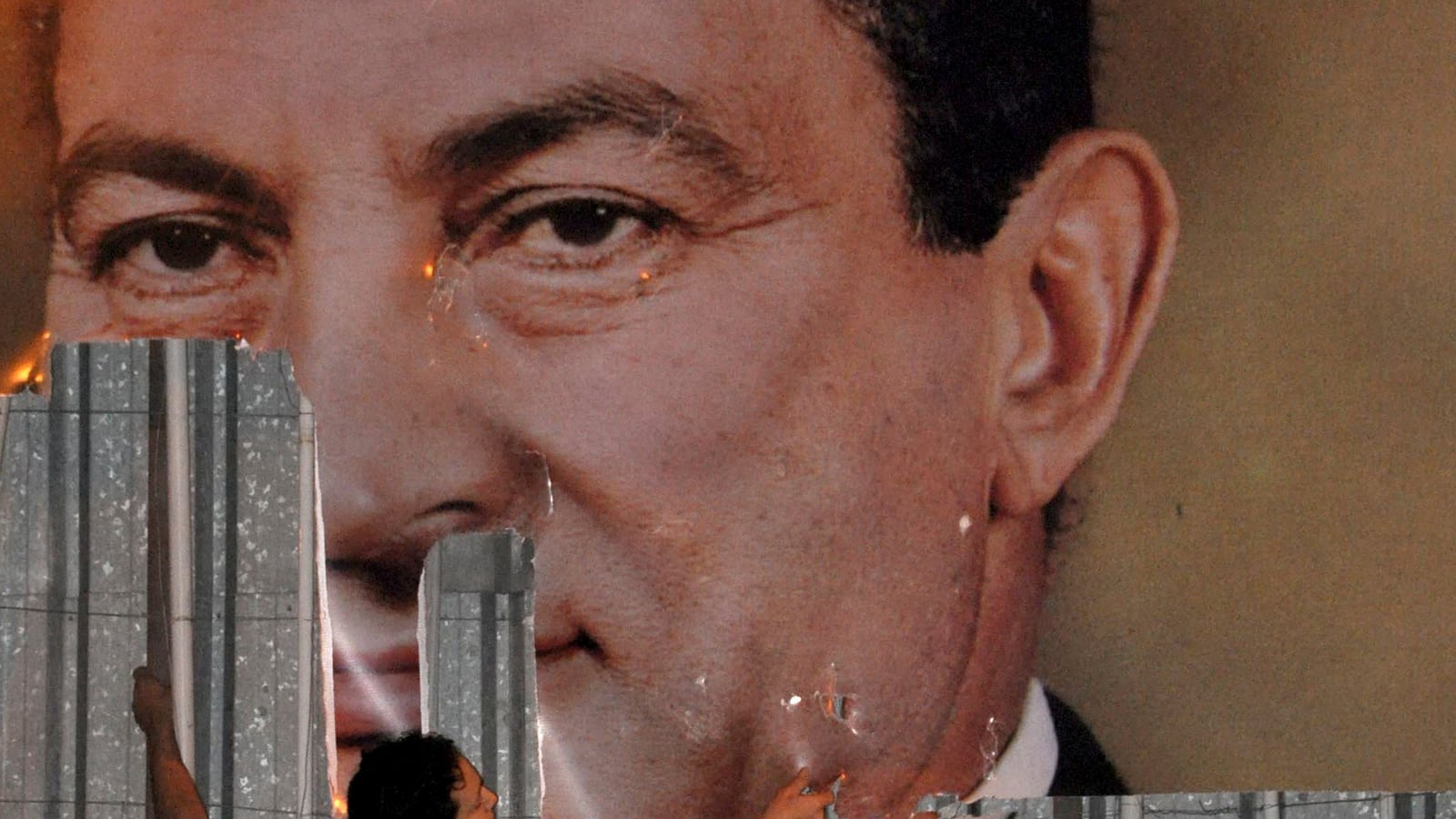

The night before he finally stepped down as Egypt’s president, thousands of protesters in Cairo’s Tahrir Square calling for his resignation heard Hosni Mubarak deliver his final address as their head of state. “A speech from a father to his sons and daughters,” he called it, and like many of his orations in the past, it was filled with lies, although he may have believed some of them himself.

Mubarak promised he would stay as president until September that year, another six months at least, because the country needed him for a transition to democracy. This, after three decades of his autocracy. This after hundreds had died in the protests against him.

The hundreds of thousands gathered in the square wanted to hear him say only one word: “Goodbye.” Amid their screams of fury, one woman could be heard shouting into a phone, “People are sick of the soap opera!”

It was a moment of idealism, filled with the hopes of young Egyptians. And then the the moment passed. Mubarak was gone, but the popular protests and clashes with police degenerated into hideous violence. The Muslim Brotherhood would use the mechanisms of democracy to win the elections that followed, but then came more protests, and the military coup of 2013 that brought in a regime even more rigid and ruthless than Mubarak’s had been.

Nine years later, after the headlines on Tuesday announcing that Mubarak had died after years of prison and disgrace, given all that has happened since his ouster and the way the so-called Arab Spring turned into a long, bitter, blood-drenched winter that continues across the region, there will be nostalgia among some for the late Egyptian president as the lesser of so many evils, even those he helped to propagate.

Mubarak had waged war against Israel, but also helped to build a lasting peace. He was considered a close ally by American presidents, until the Obama administration decided his rule was not longer tenable. Egyptians saw Mubarak as the ruthless “pharaoh” whose regime could be cruel indeed, but he was also "The Laughing Cow" bumbling his way through three decades in power as the butt of popular jokes.

There seemed to be about Mubarak an accessible humanity lacking in the other Middle Eastern tyrants of his generation. And central to his fall from power was a very personal drama.

It took place mostly out of public view—but it helps explain the president whose stubborn incomprehension of his “sons and daughters” dragged Egypt so close to ruin. Former U.S. Ambassador to Egypt Daniel Kurtzer called it the “tragedy” of the Mubaraks. “He really did feel he was the only one holding the dike,” said Kurtzer, as if beyond Mubarak lay the deluge.

Mubarak’s fall was not a story like the one that unfolded in Tunisia at the end of 2010 and the beginning of 2011, where the Arab Spring began weeks earlier, of a dictator and his kin trying to take their country for all it was worth. Although there were widely reported, poorly substantiated allegations of a $40 billion to $70 billion fortune amassed by the Mubarak family, few diplomats in Egypt found those tales even remotely credible.

“Compared to other kleptocracies, I don’t think the Mubaraks rank all that high,” one Western envoy in Cairo told us. “There has been corruption, [but] as far as I know it’s never been personally attached to the president and Mrs. Mubarak. They don’t live an elaborate lifestyle.”

On the contrary, vanity more than venality was the problem at the top in Egypt. Despite the uprising of millions of people in Egypt’s streets in early 2011, and these masses’ ringing condemnations of secret-police tactics and torture, the Mubarak family remained convinced that everything the president had done was for the country’s own good.

“We’re gone. We’re leaving,” the deeply depressed first lady, Suzanne Mubarak, told one of her confidantes as the crisis worsened. “We’ve done our best.”

The man at the heart of the story had never imagined he would hold the presidency—and when that came true, he couldn’t imagine it ending. As commander of the Egyptian air force, he had been a hero of the 1973 war against Israel, so when President Anwar Sadat summoned him to the palace in 1975, he thought maybe he was going to be rewarded with a diplomatic post, but no more than that. (Friends say Suzanne told him to try to get a nice one in Europe.)

Instead, Sadat named him vice president. Then, on Oct. 6, 1981, as Sadat and Mubarak sat side by side watching a military parade, radical Islamists opened fire, killing Sadat and making Mubarak the most powerful man in the land.

Egypt was a different country in those days, one where the government’s lies to the people went unquestioned and the police routinely intimidated the public into submission. The only television was state television, and the primary contact with the outside world was via sketchy phone lines. Some international calls had to be booked days in advance. As Mubarak’s reaction to the protests made clear, he failed to understand how the country had changed in 30 years.

Mubarak’s partner in the family tragedy was Suzanne Mubarak, the daughter of a Welsh nurse and an Egyptian doctor, who married Hosni when he was a young air force flight instructor and she was only 17. By the time she was in her late thirties, when her boys were teenagers and her husband was vice president, she set about reinventing herself as a social activist in Egypt and on the international stage.

“Suzanne is 10 times smarter than her husband,” said Barbara Ibrahim of the Civic Engagement Center at the American University of Cairo. “She’s got nuance, she’s got sophistication.”

As Egypt’s first lady, she helped to bring dozens of nongovernmental organizations to the country to try to improve Egyptian life. More than her husband and more than his inner circle of intelligence officers and military men, Suzanne had a sense of the world outside the palace.

But she also had ambitions within it. None too secretly, Suzanne guided the fortunes of her children and grandchildren, looking to establish a political dynasty that might endure for generations. The older son, Alaa, was a businessman who preferred soccer to the game of politics—a fact that brought him occasional surges of popularity over the years as a big-name, big-mouthed fan of Egypt’s national team.

The younger son, the handsome, aloof Gamal, appeared to be the anointed but undeclared heir to the presidential palace. (When writing about his rise, British tabloids never failed to mention the pharaohs’ ancient dynasties.) Gamal himself, half-joking with friends and acquaintances even as he ritualistically denied presidential aspirations, preferred to speak of the Kennedys, the Bushes, and the Clintons.

But in the spring of 2009, the family’s plans and strategies unraveled. The turning point came with the death of a child.

As the year opened, the 80-year-old Mubarak appeared firmly in control. America had a new president, Barack Obama, but Mubarak knew about U.S. presidents. He had seen four of them come and go, every one convinced that Mubarak was the only man in Egypt who could keep the biggest population in the Arab world quiet, extremists at bay, and his army at peace with Israel.

Even after the Bush administration’s brief push to democratize the Arab world, Egypt’s seemingly eternal president looked as solid as the Sphinx. The old man’s great joy in life—what put a smile on that stony face and kept him going—was his 12-year-old grandson, Mohamed, the first-born son of Alaa.

A dark-haired, dark-eyed charmer, Mohamed often appeared with the president in official palace photographs. The cover of Hosni Mubarak’s official biography showed him seated with toddling Mohamed, about 2 years old at the time, standing in front of him. Another palace picture showed the well-groomed little Mohamed a few years later talking on the phone as if playing president. At soccer matches he sat at his grandfather’s side.

In mid-May of 2009, the boy spent the weekend with gidu Hosni (grandfather Hosni) and grandmama Suzanne, as he had done many times before. But when Mohamed went home to his parents the next day, he started to complain of a pain in his head. And then he slipped into a coma.

Mohamed died a few days later in a Paris hospital, reportedly from a cerebral hemorrhage.

The devastated Egyptian president canceled a planned trip to visit Obama in Washington and could not even bring himself to attend Mohamed’s funeral. When Obama flew to Cairo a few days later to deliver a landmark speech to the Arab and Muslim world, Mubarak did not attend. And the Egyptian people, as sentimental as any on earth, regarded their president’s heartbreak with deep sympathy. Israeli journalist Smadar Peri remembers people in Egypt’s streets clamoring to speak with reporters, wishing only to express their condolences. “We are one family, and Mubarak is everyone’s father,” they told her.

“That was a moment of glory,” a close friend of the Mubarak family recalls. “If the president had stepped down, people would have begged him to stay.” But Mubarak did not step down.

Amid speculation that he was losing his grip, that he was literally dying of a broken heart, Mubarak stayed. Peri, who interviewed him a few weeks after his grandson’s death, told me later that he had lost none of his mental capacity, but that the spark behind his eyes was gone. He no longer enjoyed his work or his position or his future, but he held on anyway.

It was then that he first failed to see a way out. He had come to believe that no one could replace him, not even Gamal.

The president’s younger son had spent nearly a decade studying the art of politics in his father’s ruling National Democratic Party, ever since returning from London, where he had worked for Bank of America and then run his own company, Medinvest. He imported organizational ideas and administrative techniques from abroad, especially from Britain’s Labour Party at the time. (Then-Prime Minister Tony Blair “has taken more vacations in Egypt than God,” a friend of the family notes in passing.)

The scheme might have worked except for one thing: Gamal was not a politician. “Gamal is a nerd,” said Ziad Aly, a mobile-communications entrepreneur and an old schoolmate of the Mubarak boys from the American University in Cairo. “He was a very clever type of 4.0 student. And he continued to be clever all his life. He reads a lot. He learns a lot. And Gamal was a good investment banker. He was always at it.”

For all his technocratic brilliance, however, Gamal desperately lacked any hint of a common touch. “I think he’s sometimes misconstrued as arrogant, and I don’t think he is,” said Aly, who joined the protests against the regime at the beginning of 2011. “But Gamal has a huge problem, which is communication. He is not charismatic; he doesn’t come across as a person who is good with people. So he was looked at as maybe well-educated, maybe young, maybe a nice picture for the country—but he’s not close to us. He’s very alienated. So he cannot actually rule or lead.”

Even so, many of Egypt’s best and brightest businessmen gathered around Gamal’s standard. Some profited mightily from the association, while others set out to modernize an economy still weighed down by policies dating back to the “Arab socialism” of Gamal Abdel Nasser. Some did both, and several were brought into the government. Liberalization, privatization, and modern telecommunications began to transform the business landscape.

Sales of what had been government land and the construction of hotel and condo developments created a vast and lucrative Riviera on the Red Sea that, in turn, created enormous fortunes. Foreign direct investment increased dramatically at first, and until last year the economy was growing by 6 to 7 percent.

But the new money also created a new class of super-rich Egyptians. It stoked resentment among tens of millions of people living on the edge of survival, among the young and educated who still could find no jobs—and among the military and secret-police establishment that was, for all the government’s new business-friendly technocratic veneer, the real foundation of Mubarak’s regime.

Resentment grew against Gamal and his new ways of doing things. A longtime member of the younger Mubarak’s circle likened the situation to a factory run by an old man who knows how everything works and wants to keep things that way, no matter how badly the operation needs updating. The old man’s son comes home from college full of bright ideas about newfangled machines and processes, but they’re expensive and delicate and hard to maintain, and start breaking down. “That is the way the old guard around the president saw Gamal’s people,” said the businessman. “I think that’s the way the president saw them.”

A tight group of advisers around President Mubarak worked hard to limit his vision of the world. The most notorious was the longtime minister of information, Safwat Sharif. The story always told about him sotto voce, whether true or not, was that he worked his way up through the security services filming people in love nests. Certainly he was known in government circles as the man who made it his business to keep dossiers full of damaging material about anyone and everyone who might be a threat to Mubarak or, indeed, to himself.

“He was like J. Edgar Hoover in that way,” said one close friend of the Mubarak family, referring to the political extortions of the man who once headed the FBI. “He had the files.”

Supposed crimes were prosecuted not when they occurred, or when they were discovered, but when the prosecutions would be useful to neutralize opponents or undermine critics.

Nobody wanted to go up against that inner circle, and few in the government dared. But Suzanne Mubarak sometimes tried. Moved by her conscience and an awareness of global attention, for instance, the first lady campaigned forcefully against female genital mutilation, a practice extremely common and widely accepted in Egypt. It’s not the kind of issue the men around Mubarak liked to see raised, but Suzanne “had the courage to speak out publicly and to get this criminalized,” said Barbara Ibrahim. “She chose her battles with the security regime.”

One of the most difficult battles involved Ibrahim’s own husband, academic Saad Eddin Ibrahim, who had been Suzanne Mubarak’s thesis supervisor at American University in Cairo when she went for her master’s degree in 1980. Later, when she was first lady, he wrote speeches for her at her staff’s request. But by 2000, Saad Eddin was becoming a problem for the government. Gamal had come back from London, and Saad Eddin wrote a critical piece accusing the first family of planning a dynasty—a gomlukia, as he called it, combining the Arabic words for republic and monarchy.

With funding from the European Union, Saad Eddin Ibrahim had also trained election observers, a move the Mubarak government decided to interpret as foreign interference in Egypt’s affairs. And then Saad Eddin, sitting with friends at the Greek Club in Cairo, told some off-color jokes about the president. Someone taped them and took them to Mubarak, apparently telling him, “This is the way your wife’s friend talks about you.”

Saad Eddin spent the next three years in jail, emerging disabled because of inadequate medical care for a nerve inflammation.

“I know [Suzanne Mubarak] tried at one point to intercede on Saad’s behalf,” said Barbara, “and she was told it was none of her business.”

By the spring of 2010, as the Egyptians began to look ahead to year-end parliamentary elections and a presidential election in 2011, Gamal’s star was on the wane, even among many of his business associates.

One evening, some of the country’s wealthier businessmen spoke of the future as we sat together at a bar in Cairo’s Four Seasons Hotel. The president had just undergone gall bladder surgery at the time, and their expectation—their hope, even—was that Mubarak would be healthy enough to run again. If not, they envisioned him allowing intelligence chief Omar Suleiman to run in his place. They had no Plan C. Mubarak and his family had created a power elite as lacking in imagination as they themselves had become.

Millions of other Egyptians suffer from no such handicap, and they want a country that works differently. When steel tycoon and ruling-party boss Ahmed Ezz eliminated almost all opposition candidates in the wildly fraudulent parliamentary elections at the end of 2010, the public’s anger mounted. And in mid-January, when Tunisians brought down their country’s dictator, Egyptians began their own unprecedented push to do likewise.

As a weakened Mubarak leaned more on his army to save him, the generals’ first targets were the “businessmen” in the cabinet. Gamal’s allies were forced out. Several were threatened with prosecution. The old guard had won its first victory. Then the president himself stood down. The old guard was in charge again.

That fact would register on ordinary Egyptians soon enough, we wrote that night that Mubarak fell in February 2011. Another soap opera—or another tragedy—might begin. But this one would not be called The Mubaraks.