When I read about the controversy swirling around the children’s book A Birthday Cake for George Washington, I gave a little shudder and thought, there but for the vagaries of fortune go I.

Years ago I collaborated on a children’s book called Jump! The Adventures of Brer Rabbit. The book was a retelling of several African American folk tales first collected by Joel Chandler Harris in the late 19th century and published in a series of books that all featured Uncle Remus, a fictional former slave, as the storyteller.

My co-author, Van Dyke Parks, and I agreed early in the process to do three things. First, get rid of the dialect used to tell the stories in the Chandler books. Second, get rid of Uncle Remus. Third, stay far, far away from the Tar Baby story.

The book got good reviews and sold well enough to justify two sequels. If there was any protest, it never got back to me.

Still I always felt like we’d gotten away with something, even if I wasn’t sure what.

Because when you take a stroll through the territory of children’s literature, you’d better know where the land mines are buried.

The folks at Scholastic Books were swiftly reminded of this—twice!—in the last few days.

For decades, Scholastic has been one of the biggest, most experienced publishers of books for young readers on the planet (Harry Potter is just the tip of their iceberg). But clearly when they published A Birthday Cake for George Washington on Jan. 5, they had no idea of the ruckus they were kicking up.

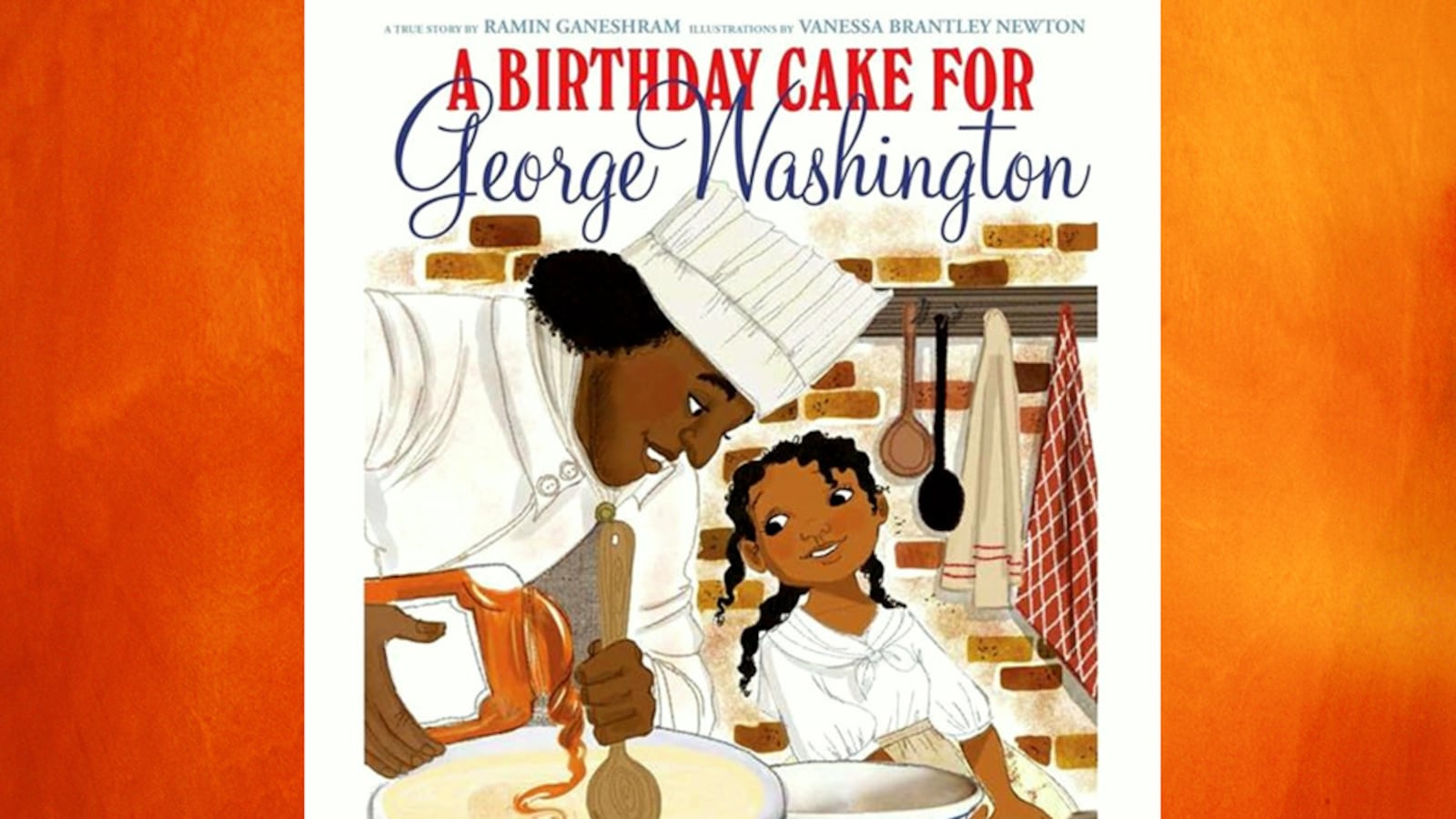

Written by Ramin Ganeshram and illustrated by Vanessa Brantley-Newton, the book tells the story, based in fact, of Hercules, George Washington’s jolly cook, who is baking a cake for his master and runs out of sugar. The problem, said critics, including the respected School Library Journal and Kirkus Reviews, was that while the story notes that Hercules was a slave, it glossed over the plight of African Americans in bondage. Kirkus called it “an incomplete, even dishonest treatment of slavery.”

The protests were successful. Scholastic bowed to the pressure and pulled the book from stores on Jan. 17.

That, in turn, set off another round of protests, this time from civil liberties champions such as The National Coalition Against Censorship, PEN American Center, and the First Amendment Committee of the American Society of Journalists and Authors, who argued that “while it is perfectly valid for critics to dispute a book’s historical accuracy and literary merits, the appropriate response is not to withdraw the volume and deprive readers of a chance to evaluate the book and the controversy for themselves.”

Nor is A Birthday Cake for George Washington the only offender. Last year saw the publication of A Fine Dessert, about a slave mother and her daughter making a dessert called blackberry fool. Written by Emily Jenkins and illustrated by Caldecott winner Sophie Blackall, that book, too, was criticized for eliding the horrors of slavery.

The irony here is twofold. First, the world of children’s book publishing is achingly forward thinking and politically correct. This is due, in no small part, to the pedagogical impulse among publishers of books for children, and the books that result are too often drearily and relentlessly on the side of the angels. For every Stinky Cheese Man or Captain Underpants, there are five picture books dealing with LGBT issues, immigrant sagas, racism, or even the Holocaust. Yes, there are picture books about concentration camps for children not even old enough to read.

Second, children’s book publishing is historically rife with examples of racism and prejudice. While this irony might seem at first to contradict the first one, it actually helps explain it: Over the past half century or so, children’s book publishers have labored mightily not to repeat the mistakes of their predecessors. They will be inclusive. They will be vigilant in rooting out casual or prejudiced ways of thinking. This is kid lit in full instructional mode.

It’s easy to see how they got to that point, because the troublesome thing about books is that they never completely go away. And a lot of the books with offensive material are in fact classics, so the whole industry is saddled with an ugly past that keeps breaking in on the present.

In the wake of the controversy over A Birthday Cake for George Washington, the Internet lit up with stories gleefully listing classic works of children’s literature that contain offensive passages.

There are early 20th century counting books (yes, more than one) called Ten Little N**gers (also the original title of Agatha Christie’s Ten Little Indians).

In one episode in The Story of Dr. Dolittle, a black man wants to marry a white princess, so the good doctor devises a way to bleach the man white.

Peter Pan and the Little House on the Prairie books demean Native Americans.

Tintin in the Congo depicts Africans as stupid grotesques who worship white people.

In The Secret Garden, the protagonist, Mary, says that “blacks are not people,” and no one ever contradicts her, although the book is otherwise dedicated to correcting her behavior at every turn.

In early editions of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the Oompa Loompas were black cannibals.

And many readers object to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn because Mark Twain (in this regard at least the Quentin Tarantino of his time) uses the word n**ger more than 200 times.

With the exception of Twain, who knew precisely what he was doing, the authors in question were almost surely clueless about their casual or unthinking racism. They were the feckless prisoners of their times, and much as we’d like for people in the past to share our enlightenment, especially people we otherwise admire, it’s just not going to happen in an unfortunate number of cases. And a couple of centuries from now, when people look back at us, they too surely will be thinking, how could they?

The case of Joel Chandler Harris is particularly relevant in this regard. A lifelong southerner and an Atlanta newspaper editor (and incidentally a friend of Twain’s), Harris was probably as enlightened as a white person could be in his time and place. If you read his Uncle Remus stories, you’ll see that to Harris, Uncle Remus was a hero. He’s certainly the smartest and kindest person, black or white, in the narrative that frames the folk tales collected by the author from former slaves.

More important, had Harris not collected those folktales, we almost surely would have missed much of a vast trove of oral storytelling (“our most precious piece of stolen goods,” Twain called them—so that’s what we were getting away with!), because before Harris, no one else had the sense to realize how wonderful those stories were, much less that they should be recorded for posterity. Whatever sins he may have been guilty of, Harris knew at least that much. James Weldon Johnson called the 185 stories published by Harris “the greatest body of folklore America has produced.”

(I’m completely ignoring the tangled history of Disney’s Song of the South, the animated and live action film based on Harris’s stories, since none of that can be blamed on Harris. I will only say that the racism and prejudice embedded in a host of Disney projects merits several dissertations.)

The point with Harris, and nearly all the other so-called racist writers of classic children’s books, is that they weren’t haters. Racism wasn’t on their agenda the way it was with, say, D.W. Griffith or Leni Riefenstahl. Try watching The Birth of a Nation or The Triumph of the Will, and you’ve got a real problem to sort: here are films of genius with despicable messages at the very heart of the stories they tell.

But with most of the classic children’s books tagged as racist, the prejudice crops up more as a reflection of the times in which the books were written. People on the frontier prairie did demonize Native Americans and they did go to minstrel shows, just the way Laura Ingalls Wilder describes them in the Little House books. To pretend otherwise does a disservice to history.

Or try this: excise or merely skip the offensive passages in problematical classics and see how much damage you do. Take away the dialect and the character of Uncle Remus, and the trickster tales he collected are in no way diminished. Rejigger the text and redraw a few illustrations for Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and the Oompa Loompas are, well, just Oompa Loompas.

This doesn’t always work, of course. Tintin in the Congo, to cite but one example, is appalling no matter how you look at it.

The dilemma of racism and prejudiced language soiling certain works of children’s literature is real enough. However, obsessing over racist passages in otherwise beloved books ignores a far more pernicious problem: until roughly the last half century, children’s literature was overwhelmingly, unrelentingly white. The authors were white, and so were the characters in their stories. Imagine the damage it does to a child who isn’t white to grow up reading books where he or she can’t identify with anyone in the stories. Surely this corrodes a child’s sense of self in far more lasting and insidious ways.

To be sure, children’s book publishers have labored mightily—and yes, sometimes wearisomely—to redress this insult in recent decades. Books for children featuring people of color and varied ethnicities now abound, and if they do not redress the damage done by Anglo-centric books of the past, it’s not for want of trying. Maintaining that progressive spirit deserves our energy far more than any effort to condemn or banish old books unfortunately tainted by the mores of the past.

Of course, parents, teachers, and librarians—anyone who puts books in the hands of children—should know what’s in those books and be prepared to discuss with young readers where those books go astray. The first lesson they could teach would be that we live in a more enlightened time than the times that produced those classics. It doesn’t mean we’re better people, but it does mean we’re luckier.