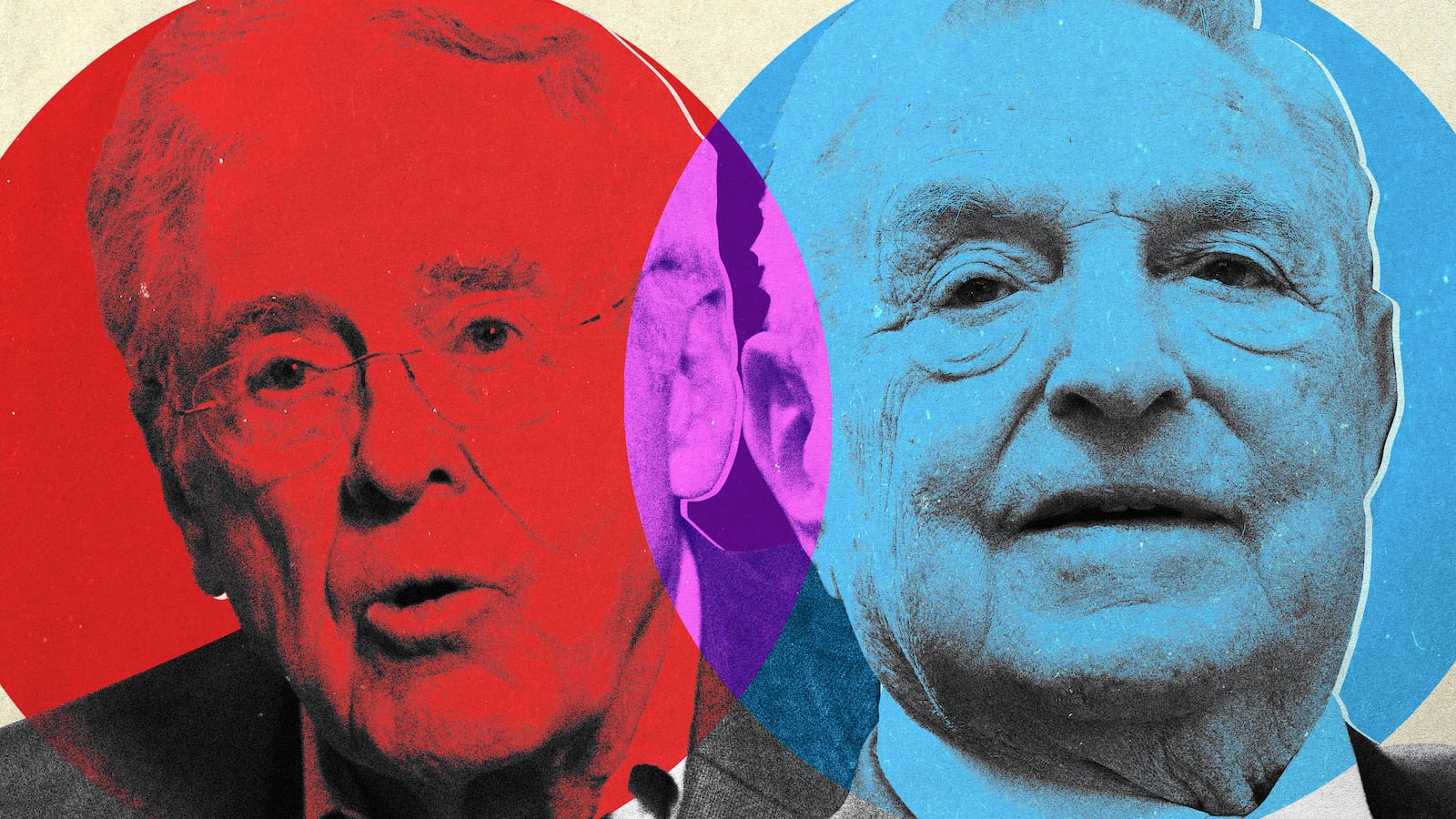

In “one of the most remarkable partnerships in modern American political history,” the left’s favorite enemy, Charles Koch, and the right’s favorite enemy, George Soros, are combining forces and finances to fund a new think tank, in Washington: The Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft that aims to end the American “forever wars” that have defined the first two decades of this millennium, and move past the foreign policy that led to them.

The Institute is named in honor of John Quincy Adams, who when Secretary of State, wrote on July 4, 1821, an admonition to his fellow Americans to try not to spread American power abroad:

[America] goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own…

She well knows that by once enlisting under other banners than her own, were they even the banners of foreign independence, she would involve herself, beyond the power of extrication, in all the wars of interest and intrigue, of individual avarice, envy, and ambition, which assume the colors and usurp the standard of freedom. The fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly change from liberty to force… She might become the dictatress of the world: she would be no longer the ruler of her own spirit.

This advice was revived by revisionist socialist historian William Appleman Williams in the late 1950s, and became a credo for anti-imperialist activists on the left. Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., who while serving in the White House under John F. Kennedy, had been hostile to Williams, later began to reference Adams’ advice himself during the Vietnam War era. And in our current era, it is often referred to by writers in the pages of The American Conservative.

Following Quincy’s approach, the Institute promises to work on “ending endless war,” “democratizing foreign policy,” and favoring diplomacy. The use of armed force,” its principles assert, “does not represent American engagement in the world.”

Their attempt to build a bi-partisan think tank composed of opponents of the exercise of U.S. power abroad and of any military intervention, especially war, is not a new phenomenon. But it is a new attempt—this time with real money behind it in a $3.5 million first-year budget, including $500,000 each from Soros’s Open Society Foundation and the Charles Koch Foundation. Founding member and anti-interventionist scholar of the U.S. military and foreign policy Andrew Bacevich notes the group will invite “both progressives and anti-interventionist conservatives to consider a new, less militarized approach to policy” instead of “endless, counterproductive war.”

That’s a position as old as the American century, and one again having a moment after 17 years of war in Afghanistan, and with 5,200 U.S. troops still in Iraq.

It is one certain to gain support among editors of The Nation on the left, and The American Conservative on the right—both magazines that have published anti-interventionist articles by Bacevich. When the latter magazine debuted in 2002, I wrote that much of its content “could just as easily have appeared in the flagship publication of America’s left.” Both magazines have featured writers who oppose U.S. globalism, supported protectionism, and as the editors of The American Conservative put it, “point to the pitfalls of the global free trade economy” and warn against U.S. “global hegemony.” In today’s United States, those themes are even more invoked by many Trump supporters.

What the think tank urges, it is clear, is opposition to any U.S. leadership that seeks to use American power on behalf of its goals, including that of democratization of authoritarian and totalitarian regimes. They see the problems in the world arising from the leaders of America seeking expansion of a hegemonic U.S. empire.

The roots of this line of thought—which opposes U.S. power abroad in nearly all circumstances, and ascribes the world’s problems to American leaders seeking expansion—began in the 1930s, before Pearl Harbor, when influential figures of both the left and right belonged to the isolationist America First Committee. Its ranks included Norman Thomas, leader of the Socialist Party in the U.S, and conservative businessmen Robert E. Wood of Sears, Roebuck; H. Smith Richardson of the Vicks Chemical Company, and Chicago Tribune publisher Robert R. McCormick. Earl Browder, head of the American Communist Party, did not belong to the Committee, but had the Communist Party create its own new peace group (it ended it after Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941).

After the end of World War II, as Harry S. Truman forged a bi-partisan coalition to assert American power to both fight Communism in Europe and to help Europe rebuild through the creation of NATO and the Marshall Plan, he received fierce opposition from the left and the right. Truman’s former Secretary of Commerce, Henry A. Wallace, worked along with Communists who favored a soft policy of cooperation with Stalin, and who accused the United States of aggression and favoring war.

On the right, Robert A. Taft, the senior Senator from Ohio nicknamed “Mr. Republican,” initially opposed the Marshall Plan and, as did Wallace, opposed NATO. When the Communists in Czechoslovakia staged a coup in 1948, overthrowing one of the only countries in Eastern Europe that had a democratic pre-war heritage, Taft argued that the country rightfully belonged in Russia’s sphere of influence, the same argument made by Wallace. The Soviets, said Taft, were “merely consolidating their position.” No wonder Wallace said that Taft’s foreign policy “was most liable to keep the peace.”

A Truman adviser, Joseph P. Jones, put his finger on the strange alliance when he wrote that the most outright opposition to Truman’s bi-partisan foreign policy came from “the extreme Left and the extreme Right… from a certain group of ‘liberals’ who had been long strongly critical of the administration’s stiffening policy toward the Soviet Union, and from the ‘isolationists,’ who had been consistent opponents of all foreign-policy measures that projected the United States actively into World Affairs.”

The left-right alliance re-emerged during the heated and sometimes violent opposition to the Vietnam War. A formal attempt to build unity was started by the Old Right libertarian Murray N. Rothbard, and his free market colleague Leonard Liggio. They started a journal, aptly titled Left-Right, that I wrote for and which sought out anti-interventionist articles from both sides. Rothbard’s writings could be found in right-wing and libertarian outlets, as well as in the preeminent mass left-wing magazine, Ramparts, and the intellectual New Left publication, Studies on the Left. At one anti-Vietnam War rally, Liggio spoke alongside the late then-Marxist historian Eugene D. Genovese, who was well known for saying at Rutgers University during a teach-in, that he “welcomed the impending victory of the Viet Cong.”

During Bill Clinton’s presidency, the left-right alliance appeared yet again while the U.S. supported the 1999 bombing of Serbia’s military infrastructure and it its capital city of Belgrade during the Kosovo war, as Serbs were undertaking massacres of the Bosnian Muslim population, and the Milosevic government of Yugoslavia engaged in repressive and violent acts against Kosovo Albanians. Leftists in the U.S. supported the opposition of the radical International Answer group, an offshoot of a Trotskyist communist sect. Pat Buchanan spoke at rallies opposing the bombing alongside the self-proclaimed Marxist columnist, Alexander Cockburn.

A new group formed a website to tie their movement together, antiwar.com. After its founder Justin Raimondo died this week, National Review noted in his obituary that, “Like his political idol, the radical libertarian Murray Rothbard, Raimondo always had some new cockamamie left-right alliance against the respectable people in mind.”

During the war in Iraq and the long war in Afghanistan, an informal left-right alliance again emerged. International Answer and Pink Code on the left held demonstrations, and on the right, Pat Buchanan spoke out frequently, always with a tinge of anti-Semitism, as he wrote about the Jewish administration members who brought us into the war—avoiding mention of all those in the Bush administration who weren’t.

As Armin Rosen details in an investigatory report in Tablet, Charles Koch has already funded anti-interventionist foreign policy institutes at universities, including a prominent one at Harvard led by Stephen Walt, who co-authored with John Mearsheimer an influential 2007 book, The Israel Lobby. As Rosen writes, Koch’s main goal is to “build an intellectual and policy infrastructure to advance their ideas because their views often haven’t had much support within the Republican Party.”

During Obama’s presidency, attempts were again made to forge a left-right coalition against an interventionist foreign policy. It was hard to accomplish, since Republicans and conservatives had a deep hatred for Obama, and Democrats a fierce opposition to any attempt to continue the previous Bush administration’s policies. Nevertheless, two leftist figures, Medea Benjamin of Code Pink and Wisconsin socialist scholar Paul Buhle, tried to do that with a Feb. 2010 conference called “A Left-Right Alliance Against War.”

Working with Buchanan supporters, they sought to found a “patriotic antiwar movement” that they hoped would gain the support of business and military leaders “who have become opposed to extreme militarism.” Participating was Doug Bandow who worked in the Reagan administration, Jesse Walker from Reason magazine, and Daniel McCarthy from The American Conservative. Liberals attending included Nation magazine editor Katrina vanden Heuvel, Ralph Nader and Michael McPherson, representing Veterans for Peace. The group hoped to work as well with Ron Paul’s supporters and Pat Buchanan’s followers, thus bringing together paleoconservatives and libertarians.

Buhle and co-author Dave Wagner believed for the first time, “we’ve arrived at that moment” when a left-right alliance could be created, and lead to “dialogue between Right and Left and even for common action against the war.” No other hopes existed for “confronting the war-drunk leadership of Republicans and Democrats alike.” Despite the goals of these few stalwarts, without important intellectual participants and no real money behind the group, nothing came out of their attempt.

Now, with a president who himself leans to isolationism, a new institute combining opposition to the old mainstream foreign policy from both right and left, he and Soros obviously believe they finally have a real chance to change U.S. policy in the anti-interventionist direction. Elliott Abrams, now working on the Venezuelan issue in the State Department, told Rosen that “the isolationist arguments have more of an audience at both ends of the political spectrum,” and he feared that one should pause before saying “they can’t have any impact.”

The institute also will work to urge Trump to soften a hard line towards Iran, and especially to get the U.S. to go back to the Iran deal negotiated by President Obama. One of its founding members, Trita Parsi, formerly head of The National Iranian-American Council, worked hard on behalf of the Obama policy. Leaving that group, he intends to carry on his work of changing U.S. policy towards Iran and urging Trump to follow that path through the Quincy Institute.

Bacevich notes that if Trump follows their lead, and by “ignoring those who call for yet more war, he just might begin the process of repairing the damage done of late to this nation’s credibility.” A person close to the Quincy group told The National Interest, “Trump may come to realize that he can count on this diverse coalition, including the Quincy Institute, to back his moves to end endless wars.”

Perhaps Columbia University Professor Stephen Wertheim and Mark Hanna of the Eurasia Group Foundation put it best, writing that if Democrats are smart, instead of just attacking Trump, they should offer “a genuinely pro-peace message-standing firmly against Trump’s bellicosity as well as decades of bipartisan military intervention.” It should be easy, they think, since Trump promised a new non-interventionist policy and failed to deliver it.

Of course, not all their arguments are wrong; one can strongly oppose U.S. support of Saudi Arabia’s horrific war in Yemen, and still favor a strong leadership role for the United States. One thing is certain. Existing think tanks like The Heritage Foundation, Brookings Institute, American Enterprise Institute and the Carnegie Foundation will now have a serious run for their money. And indeed, Trump may listen to what they say.