On Monday, Feb. 26, California gave the official green light for self-driving cars without humans inside to begin testing on public roads. The first permits could be issued as early as April 2. It’s an exciting time for Uber, Waymo, Lyft, Tesla, and other companies developing technology to automate labor and drastically reduce labor costs.

But as a nation, we’re not even remotely prepared for the changes that automation will bring. According to McKinsey and Bain, automation will eliminate 20 percent to 30 percent of American jobs by 2030, just over a decade from now. The unemployment rate during the Great Depression was 25 percent. If we want to understand the devastation to come, and the fragility of America today, the trucking industry—the top employer in 29 states—is a good place to start.

THINGS FALL APART

Let’s say it’s 2022, and Mike, a career trucker, owns a small company with 10 trucks and 15 drivers. He can no longer find enough work for his crew as self-driving trucks hit the highways. He sees his life savings about to go down the tubes because like many truck drivers, he owes the bank tens of thousands of dollars in loans he took out to buy his vehicles. He says to his guys, “Screw this. We can’t be replaced by robot trucks. Let’s go to Springfield and demand our jobs back.” He leads a protest in Illinois, and hundreds of underemployed truckers join in, some of them bringing their vehicles and blocking major highways. The police respond but they are reluctant to use force. The crowds multiply as more drivers and rioters arrive.

Inspired by what they see on social media, unemployed truckers—who now number in the thousands—begin to protest in other state capitals. The National Guard is activated and the president calls for calm, but disorder grows. Various anti-government militias and white nationalist groups arrive in each state to support the truckers and take advantage of the chaos. Some of them bring weapons, and violence breaks out in several states.

The President calls for a return to order and says that he will meet with the truckers. But the protests morph into many distinct conflicts with unclear demands and fragmented leadership. The riots rage for several weeks and dozens of businesses and drugstores are looted. In the aftermath, there are dozens dead, hundreds injured and arrested, and billions of dollars worth of property damage and economic harm, similar to the Pullman Strike of 1894 that killed 30 people and caused the equivalent of $2.2 billion in damage in response to low wages.

Things continue to deteriorate. Hundreds of thousands stop paying taxes because they refuse to support a government that “killed the working man.” A white nationalist party arises that openly advocates “Returning America to its Roots” and “Traditional Gender Roles,” and it wins several state races in the South. A shooter arrives in the lobby of a technology company in San Francisco and wounds several people. Tech companies hire security forces, but 30 percent of employees request to work remotely due to a sense of fear. Several tech companies move to Vancouver citing a desire for employee safety. The California secession movement surges as state officials move to protect the border and implement checkpoints.

There is already a nascent movement among technologists, libertarians and others in California to secede on economic grounds—about one-third of Californians supported secession in a recent poll, up considerably from earlier levels. One can imagine California holding a referendum to secede in response to events elsewhere in the country that are perceived as atavistic and regressive. An independent California would be the sixth largest economy in the world. Though unlikely, California’s departure would permanently tilt the country’s political balance, which could be appealing to the party in power.

Maybe the scenario I sketched above seems unlikely. To me, it seems depressingly plausible. The truck drivers are obvious but there are dozens of less obvious labor categories that are set to similarly shrink. This vision assumes that we keep our economic system as it is now, measuring economic health by GDP, prioritizing capital efficiency above all, and treating people primarily as economic inputs. The market will continue to drive us in specific directions that will lead to extremes even as opportunities diminish at every turn. And automation will soon make our problems much worse.

A NATION ALREADY IN CRISIS

We are already suffering the early fallout of increasing automation. Reports of low unemployment are incredibly misleading—our labor participation rate has fallen to 62.7 percent, a multi-decade low, comparable to the rates of El Salvador and the Ukraine. 95 million Americans are out of the workforce, including nearly 1 out of 5 adults of prime working age. Opioid abuse is surging and disability rates are climbing. Our life expectancy has declined for 2 straight years, almost unheard of in a developed country, in part because of a spike in suicides among middle-aged whites. None of this is speculative—it is our reality.

The challenges are magnified because American society is not in great shape right now. Public faith in the media and the government are at record lows. This mistrust weakens our ability to recognize what is happening, despite an increasing consensus among experts and scholars. The President of MIT recently declared that it is now the primary mission of the university to help society transition through this automation wave. In another era that would make national headlines and perhaps rally people. Today, it is submerged below the tweet of the day.

If we do not take big steps to address the growing automation crisis, society will become dramatically bifurcated on levels we can scarcely imagine. There will soon be a shrinking number of affluent people in a handful of megacities and those who cut their hair and take care of their children. There will also be enormous numbers of increasingly destitute and displaced people in decaying towns around the country that the self-driving trucks drive past without stopping. Scholars project a violent revolution if this picture comes to pass. History would suggest that this is exactly what will happen.

In his book Ages of Discord, the scholar Peter Turchin proposes a structural theory of political instability based on societies throughout history. He suggests that there are 3 main preconditions to revolution: 1. Elite oversupply and disunity; 2. Popular misery based on falling living standards; and 3. A state in fiscal crisis. He uses a host of variables to measure these conditions, including real wages, marital trends, proportion of children in two-parent households, minimum wage, wealth distribution, college tuition, oversupply of lawyers, political polarization, income tax on the wealthy, trust in government, and other factors.

Turchin argues that societies generally experience extended periods of integration and prosperity followed by periods of inequity, increasing misery and political instability that lead to disintegration and revolution—and according to his data, we’re in the midst of the latter. Most of the variables that he measures began trending negatively between 1965 and 1980, and are now reaching near-crisis levels. By his analysis, “the US right now has much in common with the Antebellum 1850s [before the Civil War] and, more surprisingly, with... France on the eve of the French Revolution.” He projects increased turmoil through 2020 and warns that “we are rapidly approaching a historical cusp at which American society will be particularly vulnerable to violent upheaval.”

WHERE WE GO FROM HERE

Forestalling automation and retaining jobs might help. Some would argue we should require that a human sit in every truck, only let doctors look at radiology films, and maintain employment levels in fast food restaurants and call centers indefinitely. However, it would be nearly impossible to curb automation for any prolonged period of time effectively across all industries. The result would be that certain workers and industries would be protected while others in an industry that is less core—like retail, which employs 1 out of 10 American workers—would be quickly displaced.

Automation is great for business, and it will likely raise the GDP—but GDP is an incomplete measure. We invented GDP during the Great Depression to see how badly we were doing, but even its inventor, Simon Kuznets, commented at the time that “economic welfare cannot be adequately measured” unless the personal distribution of income is known as well as the “intensity and unpleasantness” that goes into earning it.

We can’t stop automation, and we shouldn’t try. Time only flows in one direction, and progress is a good thing as long as its benefits are shared. But in the age of automation, we need to start measuring different things. Freedom from substance abuse, mental health, childhood success, average well-being—all are better indicators of how we are progressing than GDP growth.

We need to start steering our economy to serve human goals and values. It is only by changing what we are striving for that we can win this race.

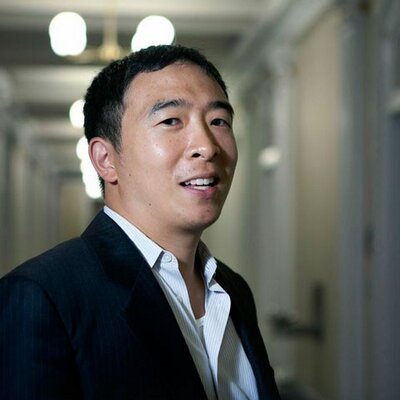

Andrew Yang is an entrepreneur running for president as a Democrat in 2020. Adapted from The War on Normal People, to be published on April 3, 2018, by Hachette Books.