On Tuesday, HBO announced the renewal of its Hawaii-based, beautifully dark, twisted satire The White Lotus for a second season. Last week, perhaps presaging the announcement, showrunner and certifiable white wealth whisperer Mike White hinted at the show’s turn toward an anthological romp—“a Marvel Universe-type thing” with a new cast and new locale to insult both in art and in life. The latest entry in HBO’s catalogue of loveless and corrosive whites doing deliciously awful things much to our amusement—a genre made ubiquitous by shows like Sex in the City, Girls, the fantasy soap opera Game of Thrones, and most recently Succession—is, as another HBO alum, Issa Rae, deemed it, “quality white mess + Natasha Rothwell being brilliant.”

But The White Lotus’ brand of Caucasian chaos adds a fresh layer of metaphysical mess: COVID-19 cases climbed in no small part due to the kind of privileged tourism the show depicts. The show winks and nods at these ills, from water shortages for Hawaiian natives as resources are rerouted to luxury hotels like the one in the show to the incessant need to flex on the gram when a filter just isn’t enough. Certainly, there does seem to be a moral center: characters like “the one brown friend” of the wealthy Mossbacher family, Paula (Brittany O’Grady), and spa manager turned unofficial grief counselor Belinda (Rothwell), negotiate their ability to resist and transcend the uber-capitalism of their environment—but when the hour is done, it feels icky to read tweets and articles from indigenous Hawaiians begging people not to travel there.

But the Hollywood machine will inevitably churn. And let’s be frank: Quality White Mess is very much our thing. Nothing hits quite like a pumpkin-tanned Tanya (Jennifer Coolidge) monologuing on lost love and onions; or emasculated Mossbacher patriarch Mark’s (Steve Zahn) oozing anxiety over his potentially cancerous twig and berries, on full-frontal display in the season’s first episode; or the shock of catching hotel manager Armond’s (Murray Bartlett) tongue running laps around his employee Dillon’s (Lukas Gage) butthole. There’s a reason why it works so well, and why the “Golden Age of Television” was defined by Quality White Mess like The Sopranos, Mad Men, or Breaking Bad. It can be invigorating when what we know about certain white people’s obtuseness is confirmed by the art we consume. It’s even more satisfying when television ratchets up their seemingly lifelong existential crises into shambolic, gut-busting hours of television.

The Golden Age was a pivotal time not only because it felt like the height of “appointment TV viewing”—that halcyon period between 2007 and 2017 when it seemed like virtually everyone would sit around the Twitter machine guffawing at the relentless TV drama whites would create and undoubtedly make worse—but because it wasn’t just white people digging into premium offerings. It signaled something that Black TV viewers had known for years: We will pay for Quality White Mess. American media is shamefully white, which of course has had the long-term impact of non-whites having to seek themselves out in the shadows of celebrated popular media. In a more integrated social order where Black people’s demands and sensibilities aren’t centered, Black viewers have what James Baldwin would call “a capacity for experience”—that is, an understanding of impulses that are distant or even antithetical to our existence. We have to be able to find joy in the ugliness of a Eurocentric world that ultimately seeks our destruction; ergo, “Quality White Mess + Natasha Rothwell’s brilliance.”

It’s seldom that that capacity for experience is reciprocated in the same ways. Take the concept of reinvention, one through which most American art is actualized. As Mark Mossbacher says after his health scare, “It’s a reminder to look at everything in a new way. And when you do, every day can be a new day, right? And if it is, it’s like you’re always being born into life, like all the time. You’re not stuck decaying or dying.” It is, in fact, a delusion, one built on comfort and privilege. Mark, as we learn a little later when he describes how much he actually doesn’t need to prove he’s not a racist, has not become a new being at all but rather a straight white man who has bought into a nuclear family model rooted in materialism hook, line, and sinker.

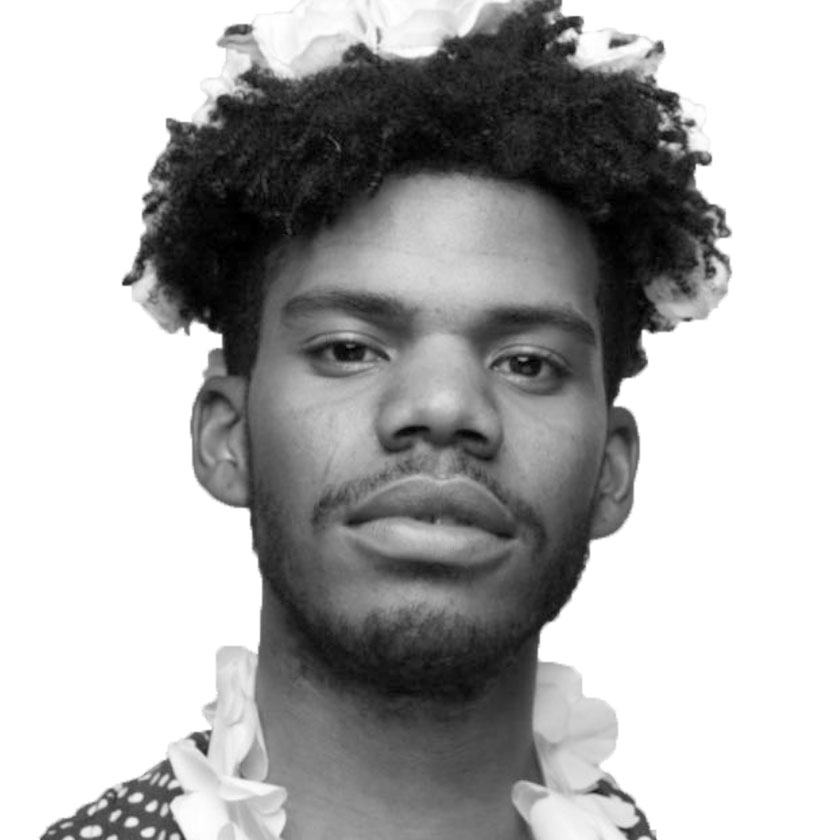

What keeps us rooted in Quality White Mess are characters like Paula and Belinda who are doing their best to navigate a truly twisted capitalist social schema. Both characters are aware, to varying degrees, how stuck they actually are, and are motivated to either join or resist the dominant culture. Paula, recognizing the thieving-ass nature of the family she’s with, plots some petty theft of her own with a Hawaiian himbo, Kai, whose family was displaced to build the White Lotus hotel where he performs tribal dances, as its benefactor. Meanwhile, Belinda draws up a business pitch to build her own Women’s Center at the behest of a drunk and effusive Tanya so she doesn’t have to keep contributing to third-wave white feminism for small coins. Both struggle in the face of those impulses, as Paula realizes it can be pretty difficult to cut one’s emotional-relational ties to capital and Belinda fails to grasp the contradictory meaning of a “Hollywood Yes.”

With the season finale of The White Lotus hitting HBO this week, it’s likely we won’t see a complete resolution of this capitalistic conundrum. (To expect it at all seems foolish.) A concrete solution is less the point of these class-conscious satires than a kind of recognition that this is just the way things are: millionaires gonna millionaire, regardless of our outcries. What remains to be seen, however, is the manner by which certain characters—or even viewers—might rebel against the neocolonial winks and real material harm caused by shows like this. While the actors themselves might remain oblivious—hey, everybody’s gotta get their bag—our society, plagued by climate, carceral and class crises, is steadily building a vocabulary that is anti-rapacious. If shit ever truly hits the fan, petty theft might be the least of these folks’ worries.