In March, three months after the body of Kristina Michelle Jones was discovered in the burned-out shell of her father’s trailer in Water Valley, Mississippi, her family became frustrated that police had not announced a cause of death or made an arrest.

That was when Jones’ sister-in-law Ashley Henley, a 40-year-old former state lawmaker and schoolteacher, decided to investigate the case herself. On June 13, Henley was found dead of a gunshot wound on the very same property—raising obvious questions about whether the two deaths were related.

Those closest to Henley told The Daily Beast that she felt she could be in danger by digging so deep to get justice for Jones.

“She’d told me that she was on the verge of uncovering something very bad. And her words to me was, ‘They may kill me, but I’m not giving up. I’m going to find the truth,’” said Rep. Dana Criswell, a friend of Henley’s who served with her in the Mississippi State House of Representatives.

“She knew she was uncovering something that she felt was very, very bad. And I think she’s been proven correct.”

What exactly Henley believed she had uncovered remains a mystery. So far, authorities have supplied just one piece of the puzzle: This weekend, they arrested Billy Brooks, whom Jones’ brother described as an ex-boyfriend of hers, for torching the trailer where she died.

But Brooks, 42, is charged only with arson; Jones’ death has not even been declared a homicide. And investigators, who are expected to release more details Monday, have not said whether Brooks has any connection to Henley’s death.

Meanwhile, law enforcement in the Republican, law-and-order stronghold is under growing pressure, facing unusually public criticism on Facebook, where there’s even a hashtag: #JusticeforAshley.

“I think that people are shocked by it,” said alderman-elect Ben Piper, the former treasurer of the DeSoto County Republican Party, where Henley lived. “There is definitely, I wouldn’t say whispers that there is something going on, but people want to investigate it. They want the state involved and multiple agencies involved.

“And I think that’s unique, because typically people back local police here. This isn’t an area that distrusts the police generally, so the fact that people are saying, ‘Listen, we need to bring the big guns in,’ it is unique. But it’s because they want justice to be served.”

Jones’ charred remains were found in the trailer on Dec. 26, 2020. The death certificate wasn’t issued until May, and when it was, the cause of death was listed as “unknown” and the manner of death “undetermined.”

From the beginning, the circumstances of Ashley Henley’s sister-in-law's death struck her family as suspicious. There were no signs of gunshot wounds, Ronnie Stark, the Yalobusha County coroner, told The Daily Beast. The autopsy report described Jones’ body as “charred,” but said there was no sign of smoke inhalation—a sign that she may already have been dead when the fire began.

“My sister was a great person,” Brandon Henley, Jones’ brother and Ashley’s widower, told The Daily Beast. “She had a great heart. She just couldn’t get her priorities straight,” he said.

“She liked to have fun, she liked to party. She played the game, you know what I’m saying? She had men taking care of her, she was dating multiple men. My sister was not doing things she was supposed to be doing.”

Over the next five months, the slow pace of the investigation into Jones’ death infuriated the Henleys. On April 6, Ashley wrote in a Facebook post, “We will find out who did this, with or without help from Yalobusha County. She’s not the first to die like this down there, but I’m going to do everything in my power to make sure she’s the last. Her death will not be [in] vain.”

Henley and her husband Brandon had transformed the crime scene into a cry for justice, leaving the burnt remains of the trailer in place and putting up a large wooden sign bearing pictures of Jones and the words “I WAS MURDERED.”

On the morning of June 13, Ashley Henley left her home in Southaven, Mississippi, a Memphis suburb, and headed an hour south to trim the grass of the Water Valley property. When Brandon did not hear back from his wife for several hours, he sent a neighbor to check on her. She was found in the yard, dead of a gunshot wound to the head.

Henley, a maintenance technician, told The Daily Beast he believes his wife was killed to silence her.

“She was assassinated, I’ll say that to anyone, any place anywhere,” he said. “She was killed because we were pressuring the government to do their damn job. She was killed fighting for justice for my sister.”

“My mom is terrified that someone is going to come after me,” he added.

As was the case in Jones’ death, the Yalobusha County sheriff’s office is leading the investigation into Henley’s death. The sheriff’s department said that Sheriff Mark Fulco has been out of town since last week at a sheriff’s convention and referred all questions to the DA’s office.

Assistant District Attorney Steven Jubera told The Daily Beast that any potential connection between the fire, Jones’ death, and Henley’s slaying was still being investigated.

Brooks is being held at the Yalobusha County Detention Center and could not be reached for comment. Reached via email on Sunday, Brooks’ wife Melissa told The Daily Beast that “there is no doubt that he is innocent,” but said she had been advised by her husband’s attorney not to comment further. That attorney could not be reached for comment.

Rather than quieting criticism of local law enforcement, the belated arrest of Brooks seemed to cement the idea among some that investigators had dragged their feet in trying to determine how and why Jones had died.

“I mean, it seems suspicious that an arrest had not been made until right after the attention Ashley’s death received,” Criswell said. “Now all of a sudden that crime is solved? It just seems too convenient.”

Jubera said law enforcement had been waiting on a final autopsy report from Mississippi’s perpetually backed-up medical examiner’s office before bringing any charges. On June 9, four days before Henley was killed and just over a week before Brooks’ arrest, the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation, the Sheriff’s Office, and the fire marshal met with him to go over the case.

“We understand that Brandon Henley has suffered a great loss with the loss of his wife recently, and he’s still in pain from the death of his sister six short months ago, but the investigating agencies and district attorney’s office follow the evidence where it leads,” Jubera told The Daily Beast.

This past week, the sheriff’s office brought in the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation, which had already been involved in the Jones investigation, to assist with the Henley case. But the scope of their involvement is limited to what the Yalobusha County Sheriff’s Office requests.

“As far as anything regarding the case, we’re just helping,” said MBI spokesman Major John Poulos. “We’re offering any of our resources that they need.”

As of late last week, Henley’s body was waiting in a morgue in Yalobusha County until an exam table at the medical examiner’s office opens up.

She leaves behind a 15-year-old son and a husband she’s known since she was 15 herself, when she reluctantly gave him her pager number at the Southaven Cinema 6, where she sold concessions. That night, Brandon said, they talked until 5 a.m.

“I told her a few days later that I was going to marry her,” he told The Daily Beast. “She said, ‘You can’t say that.’ I said, ‘I will say that.’

“She’s been the love of my life since the day I met her. Now my son doesn’t have a mother. She’ll never see him graduate. She’ll never meet her grandchild,” he added, his voice shaking.

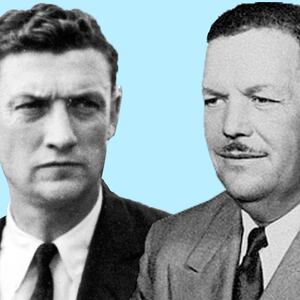

Ashley Henley was best known in her home state as a lawmaker, one of five ultra-conservative House candidates from DeSoto County to unseat incumbents in the 2015 Republican primary. From the moment she walked into the state Capitol in Jackson, she stood out.

Mississippi’s state legislature is more of a boys’ club than almost any other in the country. When Henley was elected in 2015, just 15 of the 122 members of the House were women. And rather than try to become an honorary member of that boys’ club, her former colleagues say, Henley boldly embraced being a mother in office. Every single day she showed up at the Capitol, she had her young son, Landon, often dressed in coat and tie, in tow.

“I don’t know how she ever got elected, and I mean that as a compliment, because she just was not a political animal in the way I think about my other colleagues,” said former Rep. Roun McNeal, who was Henley’s desk-mate during her time in the legislature. “She just worked harder than anybody.”

Colleagues from the legislature said she was often the first lawmaker in the building each morning and the last to leave at night.

“Our joke among the DeSoto delegation—we would go to dinner and then come back and she would tell us what the bills were about,” Criswell said and laughed. “She made a decision before she was elected that she was never going to eat with the lobbyists and never going to let them buy her meals, and she didn’t take a bite they bought.”

When she lost re-election in 2019 to a Democrat—by a mere 14 votes—she didn’t just challenge the results, Piper said, she double-checked each voter’s address.

“She fought it all the way to Jackson. She was not the type of person who said, ‘OK, well this is the answer I’m given, so I’m going to deal with it.’ She’d push back. And I think that resonates with what’s going on right now [with her investigation into Jones’ death]. She was given an answer and she didn’t think that was an acceptable answer.”

Brandon Henley told The Daily Beast that his wife never told him details about what she knew. He said everything she had learned was on her phone, which is now with the Yalobusha County Sheriff’s Office.

“She was very secretive and private with what she was looking at, because she didn’t want to make an accusation before she had the truth,” Criswell told The Daily Beast. “I asked her [what she knew] many of the times I talked to her, and she said, ‘When I have all of the information right and have it all ironed out, I’m going to the Attorney General.’”

Henley’s friends and colleagues said they plan to continue her pursuit of justice.

“One of the things Ashley taught us was to risk it all to do what’s right. And if we have to speak up, then that’s what we’re going to do. We’re going to find out the truth,” Criswell said.