There are legendary parties and then there are, well, differently legendary parties. And being forever connected with a legendary party can emphatically be a gift from the Bad Fairy too.

Fernanda Niven, a mainstay of social Manhattan for many years, married longtime to Jamie, a Sotheby’s executive, will not, I imagine, give you an argument about that. So let’s whoosh down the wormhole of time to 1963.

Fernanda Wanamaker Wetherill was 18, pretty, and the great-granddaughter of a Philadelphia department store magnate, and would be described some years later by New York magazine as “the most famous debutante in America since Brenda Frazier made the cover of Life magazine in 1938.”

The party—a pre-debutante party rather the Full Monty of a coming-out—was held at the Southampton estate of her stepfather and the 800 guests included grown-ups, such as the Duke of Marlborough, Joan Fontaine, Charles Addams and Mrs. Henry Ford.

Most of the invitees—it was, after all, a deb dance—were young ‘uns from the same background as the hosts.

The oldies duly went to bed, but the party roared on until 6.30am when about a hundred revelers, accompanied by a band playing rock and roll, made their way to Ladd House, a grand neighboring beach house, which had been rented for the male guests by their host.

Subsequent goings-on would follow Brenda Frazier into Life, not on the cover, though, but as a juicy picture-packed six pager within, headlined ‘A Wanamaker Debut Begins … And Ends In A Rampage.’ A subhead weighed in with ‘Young People’s Don’t Give A Damn Attitude Hits A New Extreme.’

Another, more ominous subhead, read: ‘Parents Are Afraid of Their Children.’

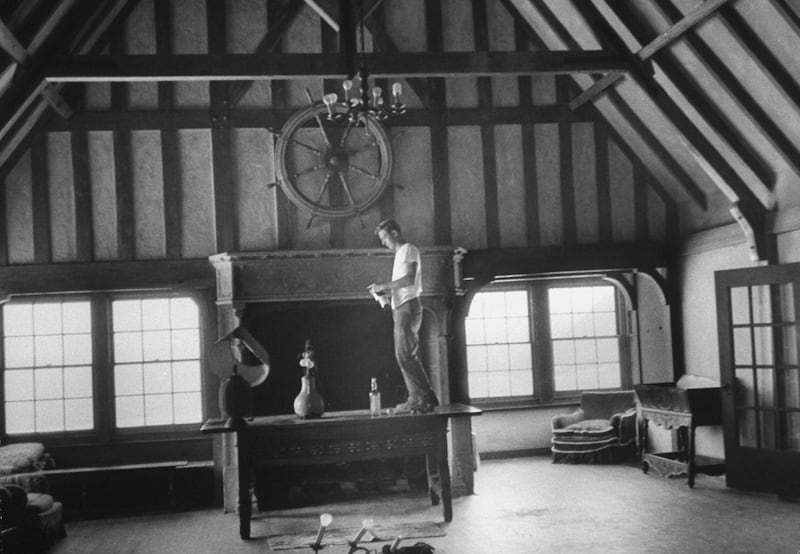

Actually, a look at the records suggests that Life’s analysis was somewhat sweeping. There was some climbing of a mantelpiece in the guest house, and one youth, channeling Tarzan, launched himself at a chandelier, but ended up in a mound of crystals on the floor.

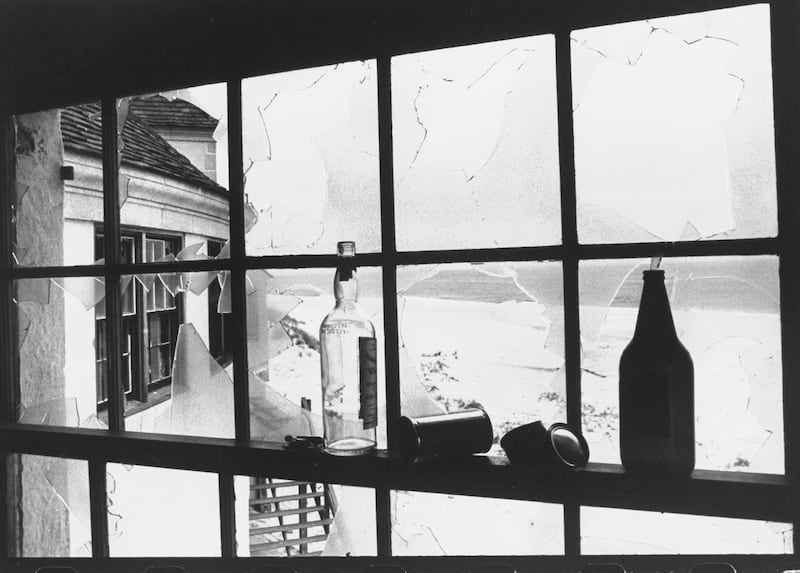

The rock group departed the beach house, along with most of the dancers. As to what then took place, the pictures tell the story. Few of the hundreds of windows were unbroken, the curtains torn down to serve as blankets. Much furniture wound up on the beach.

“When we arrived at 4pm it was a shambles,” Donald Finley, the local police chief, told Life. “We looked high and low for bodies.” There were fourteen indictments, one of a young woman, but all charges were dropped. Most of the mayhem was blamed on gatecrashers.

A psychoanalyst wrote in Life that “The Southampton rampage was an expression of mass psychosis—mass madness.”

Well, maybe to that, but certainly it was an expression of a very specific time, and a time which was ending. When I had been at Cambridge a couple of years before the Wanamaker party there was an annual folly called Bayswater Beagles.

My memory is beyond blurry on this, and Google fails me but I seem to recall it being a peripatetic scrimmage, a fake beagle hunt, but with no dogs, no quarry, all human, car to car, on the London subway system—the thinking being that we were Cambridge men, so who was going to stop us?

Well, you wouldn’t want to try that these days either. A debutante would tell that in 1960 she was in a sleeper on a train to Scotland and heard that the Everly Brothers, who were then touring the UK with Buddy Holly, were shortly to be boarding the train.

“I fired over their heads with a pretending gun,” she said years later. The “pretending” gun had been a pearl-handled revolver given her to deter the evil-intentioned by her mother.

“I just wanted to get their attention,” she explained. She and the Everlys did become fast friends but you wouldn’t want to try that nowadays either. Those days of privilege are over.

It wasn’t until fifteen years after the Wanamaker affair that I came to know the Hamptons well and by then it become a resonant legend, although (or because) the world had greatly changed.

That had been 1963 and, yes, there had been a rock-and-roll band at the do but the young male guests are sleek-haired, immaculately tuxedoed.

A few months later the Beatles would do the Ed Sullivan show and ahead lay Woodstock, the Summer of Love, “Don’t trust anybody ver thirty”—that was Jerry Rubin—and the Year of Revolutions. The phenomenon of young people not giving a damn, although they would probably choose a different noun, would go to extremes unguessed at by Life.

Other changes are more recent, perhaps more durable. Most of the photographs in Life—the broken windows, the wreckage of the beach—were taken by a photographer working with the police.

One wonders if the mag would have run the story at such length, though, without the more intimate shots, which were described as ‘The Brawl, Seen In Guest’s Snapshots.’

You will note that the word ‘guest’ is singular. Can you imagine the saturation video and verbal coverage that the brouhaha would have got in the age of Instagram and Twitter? But maybe it’s a sense that there are missing pieces that makes legends legendary.