With many TV and film studios stuck in a ‘rona rut for the last two years, greenlighting new IP seems to have slowed to a crawl while the reboot, remake, revival cycle has kicked into high gear. The latest relic receiving a 2021 dust-off is ABC’s The Wonder Years, which remodels the 1988 sitcom of the same name. Back then, the baby boomer-courting show found a middle-class, white nuclear family, the Arnolds (and more prominently their son, Kevin, played by Fred Savage, who also serves as executive producer for the reboot) at the moral center of frivolous suburban shenanigans with the surreality of the Vietnam War as backdrop.

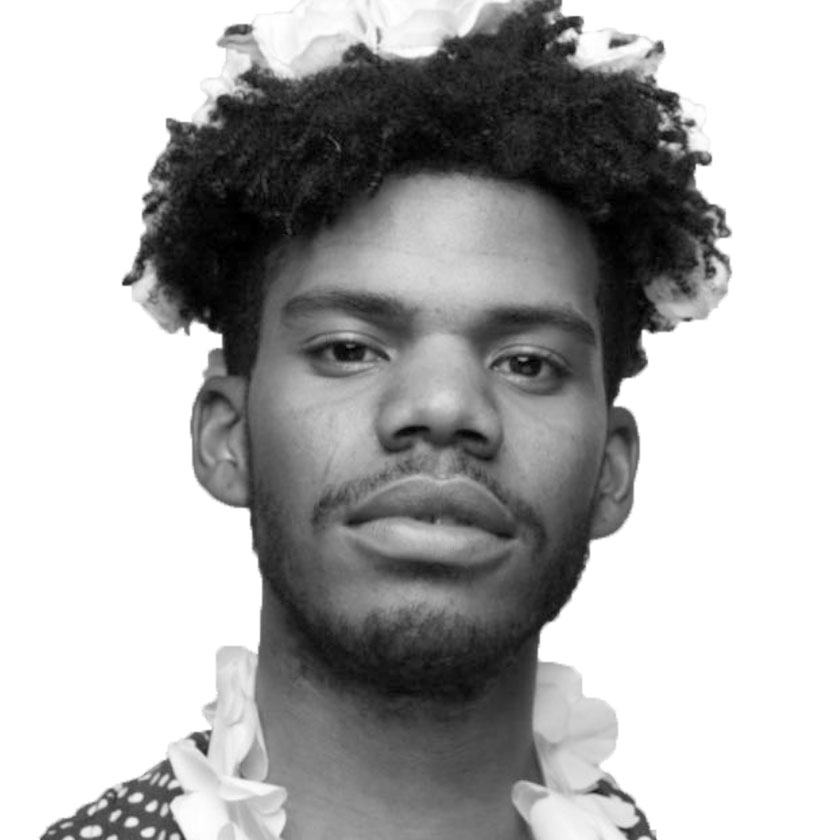

In the 21st-century redux, main character Dean Williams (Elisha “EJ” Williams) grows up in the eye of a civil rights storm as a middle-class Black kid living in Montgomery, Alabama, in the midst of social upheaval. With the always amiable Don Cheadle playing his adult version, the new Wonder Years adds a Black nostalgic gloss to a particularly fervent time in Black life. But a show like this on a network like ABC, which has a penchant for creating Black shows for white audiences, begs the question of whether or not a mainstream studio’s version of the civil rights era is a vision that Black people want to harken back to. Central to that question, too, is whether or not rebooting or remaking white shows or movies with Black cast members is pushing the progressive buttons that network execs would like audiences to believe.

No one should expect any sort of Black political or social education from The Wonder Years but the metanarrative around the update does imply a level of progressive politics that the show seeks to tap into. As we’re learning in the political world, liberal politics almost never equate to more power for Black people. In fact, Black creators in both mediums would likely consider that the practice of shoehorning Black people into white uniforms actually does quite a disservice to representations of Blackness. The Black Recast, then, could be a lot more regressive than we think.

And, of course, it’s not just happening on television. The Black Recast has its tendrils all over Hollywood. Earlier this year, Warner Bros. announced the development of two separate Superman projects, with Michael B. Jordan’s production company creating a series based on an alternative version of the Man of Steel, while Ta-Nehisi Coates was enlisted to write a film version of Clark Kent. Anthony Mackie just slipped into the Captain America role without any mention of the ways that military policing has led to the destruction and corruption of African nations. We have yet to witness Daniel Craig passing his Walther PPK to the new Bond, Lashana Lynch, who has the (un)lucky privilege of being both the first Black and first female 007. No breath should be held for that action vehicle to say anything of note about the ways spies destabilize economies or kick off coup d’etats, but it’s very easy to imagine how the representation-industrial complex will tout Lynch’s casting as some sort of step forward for Blacks in Hollywood.

Representation, itself, feels like a distraction not just from the racist underpinnings of the industry but from the ways Hollywood very much exists within an imperial project that seeks to propagate false notions of reality. When reboots and the Black Recast wed, it can mask a practical issue central to the remake-industrial complex—it steals precious time and resources that could be distributed to original IP from non-white, non-straight creators. Kathleen Newman-Bremang, senior editor at Refinery29’s Unbothered, spoke to the inherent regression of the reboot-recast knot. “These reboots are absolutely taking something away from original content,” she told CBC News in July, “and they’re getting a time slot that could go to another Black, Indigenous, or person-of-color creator.” More interestingly, Black creators are almost never given the reins to a predominantly white cast. There’s a quiet belief that Black people can only write Black characters. This segregation creates opportunities for tokenism that end up glorifying a small number of non-white artists who get similar roles over and over again.

In her remarkable Atlantic cover story on the unwritten rules of Black Television, Hannah Giorgis chronicles the changing sameness of television from Sanford and Son to the present. The 20th century represented a moment where more and more Black experiences were being portrayed on screen but from the vantage of white writers who would make their Black colleagues “negotiate authenticity.” They had to portray Blackness in a way “that is acceptable to white showrunners, studio executives, and viewers.” But that process is made even more depraved now. A Black recast is, to some degree, one of the most ubiquitous examples of Blackface, wherein white executives mask their interests and demands behind a Black mask and deem it “Black art.”

Our present version of nostalgia is a multidimensional mirror. The white version of The Wonder Years was a 1980s look into a 1960s America that, having lost the Vietnam War, was ripe for revisionism. Now, as the current generation reckons with our losses in terms of race and class freedom, another revision is at hand. This time in Blackface—and perhaps even more regressive than ever before.