First Sergeant Harry Taylor and the rest of the 91st faced a suicide mission: Gesnes.

The Germans had turned Gesnes into a fortress, and a subterranean network of tunnels bored under the town connected bunkers and strongpoints. To reach the tiny French hamlet, the Americans would have to cross a full mile of open ground with no cover. And the land was “double enfiladed by machine guns and subject to the highest concentration of [German] artillery fire I have ever seen,” recalled “Gatling Gun” Parker, who would lead the assault on the town.

Despite the tremendous risk, V Corps headquarters had ordered Major General William Johnson, the division commander of the 91st, to attack Gesnes “with utmost vigor and regardless of cost.” To carry out the order, Johnson turned to Parker. Surveying the ground, Parker saw at once that this was a forlorn hope; he attempted to explain to Johnson the bloodbath that would ensue. “The position can be taken,” he argued, “but only if it is desired to pay the price, which will be very severe losses.”

Unswayed by Parker’s argument, Johnson resolutely shot back, “The whole army is being held up because this brigade has not taken all the objectives assigned to it.” Taylor, Parker, and the rest of the regiment would charge Gesnes.

Nearly a mile from the town, in the jump-off position, Lieutenant Farley Granger surveyed the battlefield through his binoculars.

“Every square yard was visible from the higher hills beyond, occupied by the enemy, and the concrete-box on Hill 255, and every foot swept by machine-gun and artillery fire. Protection, there was none—not even concealment for one man. The gullies between the hills were swept by enfilading fire from wooded hills above Gesnes, and the hillsides were commanded by nests hidden in flanks.”

To make matters worse, the 91st faced some of the Germans’ most battle-hardened elite troops: the Prussian Guards and elements of several other regiments. With plenty of time to dig in, these experienced veterans of the Western Front had all the advantages of bunkers, command of the high ground, and control of the flanks—the 91st’s assault at Gesnes faced German attacks on three sides.

Taylor, at 38 an old man in the troop, understood that the attack meant near-certain death. In Granger’s opinion, “an umpire of field maneuvers would call the task impossible and rule the regiment out.” He recalled that in a meeting with officers of the 362nd, very likely including Taylor, one officer murmured that taking Gesnes would be “impossible, that our losses would be terrible.”

Granger’s commanding officer laid down the law. “The hell with the losses—read the order!”

Gesnes would be taken, regardless of cost.

Heading into the battle, the 91st had brought limited food and water—many were starving. German shells and constant gas alarms had kept the men awake for 36 hours straight. Heedless of their exhaustion, the undaunted Wild Westerners prepared to assault, moving into position about a mile outside the town.

Sunlight filtered through the slate-gray clouds and the husks of nearby trees as the members of the 91st gripped their rifles and other weapons, primed to charge into open ground. An enemy sniper picked off men from the rear as a deadly shower of German shells landed only 20 feet in front of the jumping-off position. Frequent screams of “Gas!” cut through the din of battle. At 3:40 p.m. the officers blew their whistles, and NCOs, such as Harry Taylor, on foot with the infantry, surged ahead. Many of the 362nd yelled their Western battle motto, anachronistic in the modern killing fields of the Meuse-Argonne: “Powder River! Let ’er buck!”

Unbeknown to the mass of soldiers charging forward, according to Lieutenant William Hutchinson, a bald-headed officer in the 362nd, “the order had been countermanded, but too late—the countermand coming just after we started.” He lamented, “The colonel could not be found. I do not know that he could have prevented it entirely, but it surely could have been called off before we had all the losses at Gesnes.”

In a charge reminiscent of scenes twenty years earlier at the Battle of San Juan Hill, Parker led from the front, in the center of the first screaming wave of men. Farley Granger’s commanding officer was not as dramatic. Accepting his fate, he turned to Granger and said, “Well, Farley, let’s go.” Taylor, Farley, and the men of the 362nd left their forward fighting positions and the last vestige of cover, leaping into a hail of German lead and steel.

Granger later described the “glorious” forlorn hope: “Perhaps the charge of the Light Brigade was more spectacular, more melodramatic and picturesque, but not more gallant. It is one thing to ride knee to knee in wild delirium of a cavalry charge under the eyes of armies; it is something else to plod doggedly on, so widely scattered as to seem alone over a barren hillside against an unseen enemy’s invisible death singing its weird croon as it lurked in the air and stinging swiftly on every side. Man after man fell, but the others continued on through a ‘hell’ of shrapnel and machine-gun fire as would be impossible to exceed.”

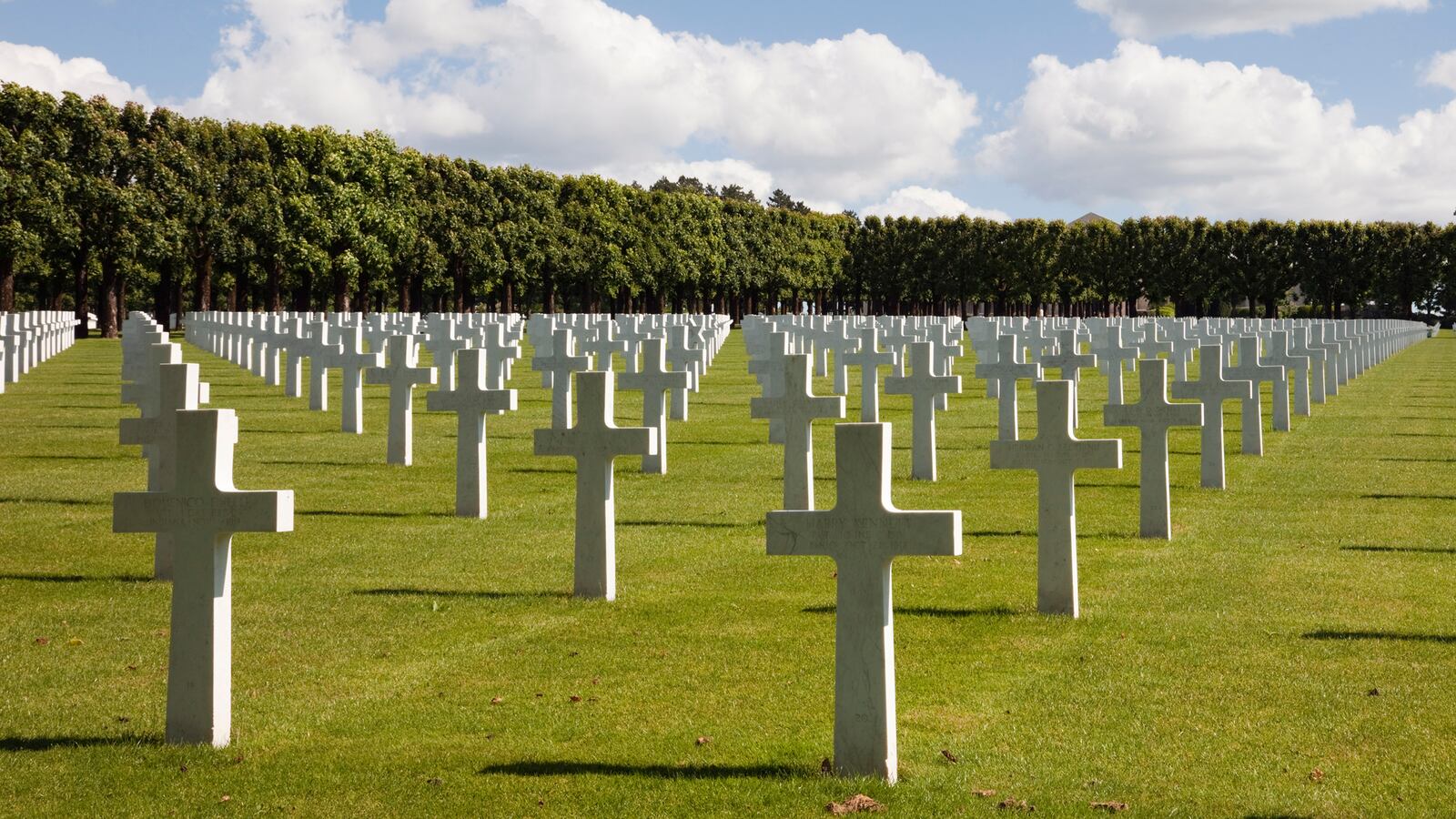

Columns of olive drab—ranchers, cowboys, and loggers—charged, only to morph into blobs of flesh and crimson rags. Heavy shells vaporized others in a spray of blood and gore. The fields outside Gesnes harvested their share of unknown soldiers; bodies of unrecognizable men carpeted the rolling plain.

A Renault FT-17, taken in an earlier battle by the Germans, obstructed the path of the advancing tide of Westerners until Granger and a company of men led by Lieutenant William Hutchinson took care of it. Charging forward, with no body armor save steel helmets, the men swarmed the tank and shot the crew as those inside attempted to flee the vehicle. Climbing into the blood-drenched FT, they turned the steel monster on Gesnes, and the tank’s machine gun tore into Boche nests. Finally, irregular groups of Westerners topped the last crest into the town. Once inside Gesnes, Taylor, Granger, and Hutchinson had their work cut out for them. “The satisfaction of some bayonet work was given to us,” recalled Granger. Small groups of men from the 362nd advanced into Gesnes, and “promptly cleared it.” However, Granger cautioned, “One must not think of this as happening in an instant—over an hour of this bloody plodding along under a tornado of missiles passed before the worst was over.”

Several men from the 91st earned the Medal of Honor that day. As would be the case at Iwo Jima during the next world war, “uncommon valor was a common virtue.” Parker said that he saw so many examples of gallantry that it was difficult to single out the men who were worthy of medals. In the 91st’s general orders, the division recognized Taylor for the valor he displayed that day—he received a Citation Star, an honor later known as the Silver Star. (Congress established the Citation Star on July 9, 1918, and in July 1932 the secretary of war converted the Citation Star to the Silver Star. Congress formally authorized the Silver Star in 1942. The U.S. Army and Air Force refer to the honor as the “Silver Star,” while the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard call it the “Silver Star Medal.”)

Parker did not witness the capture of Gesnes. Wounded multiple times, he lay near death in a shell hole five hundred yards in front of the town for two hours. Upon learning of the capture of the town and the hill beyond, he issued an order: “Dig in, hold on, and get food for your men.” In a precarious position and fearing a German counterattack, Parker “caused some wounded men near me to make a bonfire of all maps, orders, and papers in my possession, destroying everything that might possibly give any information to the enemy.”

A fate similar to Parker’s also took out Granger: a machine-gun bullet hit him in the ankle. Granger made his way off the field with four bullet holes in the flaps of his trench coat and another drilled into his canteen.

After taking Gesnes, the 362nd advanced, cutting down Germans with bullet, grenade, and bayonet. About two hundred reinforcements streamed in, swelling the American ranks. Some of the soldiers, led by Hutchinson and a few other officers and noncoms, seized a portion of the wood and the southern slope of Hill 255, north of the town. The doughboys took prisoners and captured several field artillery pieces. Hutchinson also discovered a nearby cabbage patch. After starving for three days, the ravenous men cut the cabbages in half and gorged themselves on the green leafy plants, “in the same variety of enjoyment that we would have had, if it been Crab Louie. We ate in the dark, eating cabbages, dirt, and worms, but how good it tasted.”

Scores of wounded men lay near the town, and Hutchinson attempted to find them shelter in a nearby shed. “The weather turned cold and many men suffered from loss of blood and were already shaking.”

After tending to the wounded, Hutchinson climbed back into a foxhole on the hill. Despite the German artillery fire raining down around him, Hutchinson, exhausted and suffering from exposure to gas, fell asleep next to the bodies of dead men.

Late that night, an officer espied the bald head of Hutchinson, who had lost his helmet earlier that afternoon, “in the scrape” next to the row of corpses, dead bodies of his friends, and shook him awake. “We are withdrawing,” the officer told Hutchinson.

General Johnson himself had given the order because the division was in grave danger. During the American operation to seize Gesnes, the Germans launched a massive counterattack, nearly destroying the American 35th Division on the 91st’s left flank. The enemy drove the 35th back almost two miles and fell upon the 91st. Fortunately, the 2nd Battalion of the 363rd Infantry, a machine-gun company, and other units held the line—had they failed, the Germans might have enveloped the 91st.

Acting according to their orders, divisions in V Corps had attacked independently of each other, charging forward, ignoring their flanks, and as a result meeting disaster. The 37th Division on the right flank, about two and a half miles behind, also did not keep up with the rest of the force. This strategy left individual units widely isolated and vulnerable to counterattack. Disaster loomed.

As darkness fell, the retreat from Gesnes became horrific. The memory of the withdrawal was seared into the minds of Westerners. “Everyone in our sad little procession was carrying or helping carry a wounded man. It was quite cold with a strong wind blowing rain in our faces,” recalled Hutchinson. “We stumbled along, floundering through shell holes and every now and then picking up wounded men who had not been brought off the field. We picked up a 2nd lieutenant who had been wounded early in the afternoon. Many times the stretchers gave way and the stretcher-bearers stumbled and fell. The wounded would groan and curse, and the column would halt until they were ready to move forward again. Our morale was all gone—we simply continued to stumble ahead.” The dead, far too numerous, many of them unknown soldiers, were left behind.

And then the stone-cold realization set in: The attack had been for naught. “The withdrawal finally began. We were all so tired that we did not have much feeling one way or the other at that time, but later the full truth dawned on us. We were withdrawing to the point from which we started that attack. The whole terrible afternoon and hideous night were all for nothin Taylor and the Wild Westerners had advanced more than five miles into German lines since September 26 but had outpaced the units on their flanks. Had they remained where they were, they would have been cut off, encircled, and annihilated.

What was left of the 362nd retreated from Gesnes carrying the wounded.

Granger noted, “Never have men displayed a greater devotion to duty. That is why a regiment without complete equipment or training could defeat such troops as the elite Prussian Guards, overcame positions of noted strength and still advanced, often without officers, after losing in a few minutes over 50 percent in casualties; the offensive spirit, the will to win, the fitness to win, in a word, the morale was such, the personnel was such, that victory was possible despite the greatest handicap.”

According to the regiment’s history, the morning after the attack, Taylor and the survivors slipped into a “loggish stupor. The men lay, their minds heavy with the horror of the last day, their bodies bruised and exhausted, with no more spirit than the mud under their feet.” Only handfuls of men filled out companies, which at the start of the attack had numbered 200 men—the remainder were dead or wounded. “Captains commanded battalions, lieutenants companies, and sergeants platoons, so great had been the slaughter. One company had 18 men left of its 179. Few companies ran as high as 75 [men].” Back at a field hospital, Granger met the severely wounded Gatling Gun Parker. Despite his injuries, Parker boasted to the young officer, “I didn’t see in the whole regiment a single case of cold feet—not a single yellow streak.”

While cases of desertion were minimal in the 362nd, desertion and stragglers were a sizable problem in the AEF. Estimates vary, but as many as one hundred thousand soldiers left their units in the first month of the AEF’s fighting in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive—as much as 10 percent of the total American force quit fighting and meandered to rear areas. In the 37th Division, which the 91st flanked, an inspector reported that 20 percent of the men in the unit may have been in the rear with the gear.

Part of the difficulty in calculating the volume of stragglers is that many of the men accused of avoiding duty were actually suffering from undiagnosed injuries. The doughboys’ steel helmets had no real padding, and many men experienced concussions and traumatic brain injury, also unknown at the time, after shells exploded nearby. In addition, post-traumatic stress disorder, then called “shell shock,” was common. Many of the men wandering away from the front lines were not displaying cowardice but instead were dazed or impaired as a result of these medical conditions.

Some of the stragglers had just gotten off the boat, and these raw draftees had not received adequate training. (This was generally not the case with the Marines or soldiers in the elite 2nd Division.) Some could not properly fire a rifle or throw a grenade. The inspector general in the AEF dismally reported that these “men who did not know the rudiments of soldiering soon became ‘cannon fodder’ or skulkers.”

Officers toiled to combat straggling. In First Army V Corps, they formed a 4,500-man Hobo Barrage to “systematically mop up and purge all dugouts, houses, hospitals, rail heads, YMCAs, etc.” Some wanted to shoot stragglers, but President Wilson refused to allow the practice. Instead, officers usually arrested those found lingering at kitchens, first-aid stations, and YMCA huts. Repeat offenders faced court-martial, imprisonment, disagreeable work assignments, or in some cases, public shaming. A few officers outfitted those repeatedly found dawdling behind their comrades with large signs on their backs that read, “Straggler from the Front Lines.” Not surprisingly, this strategy proved to be quite effective at encouraging the men to perform their duties. Even more effective was the technique used by one brigadier general; after his soldiers received orders to advance, he had his military police (MPs) throw grenades into dugouts behind the lines. With the rear sealed off, stragglers had no place to hide.

Desertion was not a problem in the 91st—the problem was the “butcher’s bill” from the fighting. The Wild Westerners suffered about 25 percent casualties—yet they fought on in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive until the second week of October, when the First Army transferred Taylor, Granger, and Hutchinson to Belgium. There the 91st fought side by side with the British Army, distinguishing themselves during the final days of the war.

Despite the loss of many of his close friends, a part of Granger’s youth remained in France—undoubtedly this feeling has haunted many soldiers since the beginning of warfare. “I want to live those days again; to see the bursting shells and hear them whistling for their victims; hear the frantic cries of ‘gas!’ ‘cover!’ ‘medic!’ ‘Raise the artillery!’ I want to go back to France once more—not to seek new joys or thrills, but to revive the dreams of old that are fading with the years,” Granger recalled decades later.

By September 29, 1918, Pershing’s offensive largely stalled after three days of fighting. The fact that Pershing held the AEF’s most battle-hardened and experienced divisions—the 1st, 26th, and 42nd, which had been delayed after spearheading the St. Mihiel Offensive—in reserve contributed to the lack of progress. The mighty 2nd Division also did not participate in the first phases of the American offensive.

But in October 1918, there was no time to reflect wistfully on the carnage. Most of the Body Bearers, including Color Sergeant James W. Dell, Corporal Thomas Saunders, and the Marines of Gunny Ernest A. Janson’s 49th Company headed northwest for the Champagne, where they were assigned to the French Army and would mount a forlorn attack on another seemingly impregnable German fortress: Blanc Mont.

Excerpted from THE UNKNOWNS: THE UNTOLD STORY OF AMERICA’S UNKNOWM SOLDIER AND WWI’S MOST DECORATED HEROES WHO BROUGHT HIM HOME copyright © 2018 by Patrick K. O’Donnell. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.