When Apollo 14 carried Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell to the moon for the last of the “H” missions, in late January 1971, it was met with a weeklong yawn by the press and the public. The TV networks carried live coverage of the launch and paid some mind to the long translunar coast, where misfortune had called on Apollo 13, but offered only occasional snippets of the crew’s time on the lunar surface. News from the Fra Mauro crater was dutifully passed along by the country’s newspapers, but with a palpable lack of enthusiasm. America had grown jaded about moon missions, it seemed, and on just the third to land.

But fact was, the H missions made for lousy TV. To viewers, they looked pretty much the same as Apollo 11: the astronauts were on foot. The TV camera was stationary and positioned near the lunar module. Its low-resolution footage captured the crew bouncing around base camp, doing nothing especially stirring. Apollo 14’s stretches of real drama—when Shepard and Mitchell wandered the hills, desperately seeking Cone Crater—unfolded a half mile away, and unwitnessed. In fact, the mission’s single made-for- TV moment is the only thing many older Americans remember about it: when Shepard attached the head of a 6-iron he’d smuggled aboard Antares to a lunar excavation tool and used it to whack a golf ball, crowing that it went “miles and miles and miles.”

This time was different.

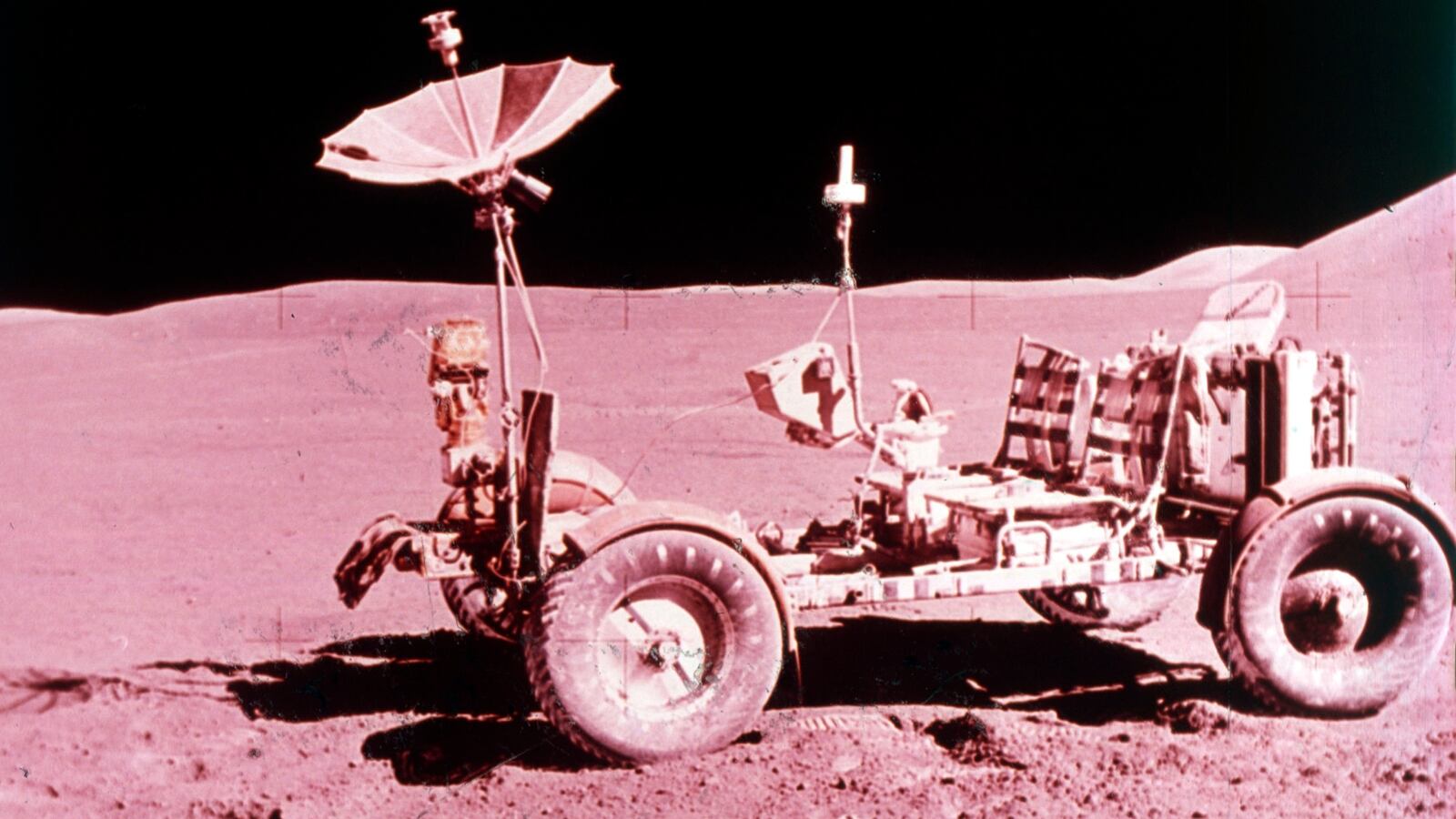

Weeks ahead of time, even months, it was plain that Apollo 15 was another kind of mission. Newspapers reported about it with renewed excitement: it would be longer, three days, with three ventures outside the lander. These astronauts would be real explorers, engaged in real science. A much-improved TV camera would follow them wherever they went. And, most important of all, they would have a car.

Journalists couldn’t stop talking about the rover. They were fond of calling it a “moon buggy,” to the chagrin of the Marshall Space Flight Center, but they seemed to have a genuine hunger for details about its design, performance, and potential contributions to lunar science. They wrote about its sky-high cost: by launch day, the press seemed to reach consensus that each flight-ready example represented an $8 million investment—a figure that involved some magical accounting, as it fell short of reality by nearly $5 million. Even at the lowball price, some stories called it the most expensive car ever made, the more so because it would be abandoned after just three days of driving.

The upshot is that Apollo 15 got a lot of attention, and much of what set it apart was the rover. Papers across the country illustrated their coverage of Saturday, July 31, 1971, the morning after the lunar module Falcon descended to the surface, with a detailed diagram of the rover’s deployment from the lander. That same morning, scores more published an artist’s rendition of the rover conquering the “lurrain”. The New York Times devoted nearly a full page to the machine. The networks began their live coverage shortly before the crew deployed the rover, followed its travels for hours, and did the same for its second venture from base.

Even advertisers piggybacked on rover fever. Consider the ad placed in the Daily Leader of Pontiac, Illinois, six days before the landing. “Apollo 15 will carry a Moon Buggy, and this Buggy has a color TV camera,” it read. “Our TV screen will seem like a window on the Moon Buggy. To get a good view of the moon, you should have a nice clear window. A new RCA color TV from Schlosser’s may be what you need. Why not be prepared for a thrilling ride on the moon?”

At 9:34 a.m. E.D.T. on July 26, 1971, Apollo 15 rose on a pillar of flame from its pad at the Cape and climbed with gathering speed past the crown of its launch tower. The sound of it took seconds to reach the nearest spectators, three miles away—a deep, almost seismic, roar, punctuated by a dry crackle of booms, each delivering a punch to the chest. Looking on were Wernher von Braun, Greg Bekker, Frank Pavlics, and Sam Romano.

The setting for the rover’s maiden voyage was well chosen: the Hadley-Apennine region, an undulating plain rimmed on two sides by mountains the size of Everest and on a third by a canyon a mile wide and nearly a thousand feet deep. In place of the featureless gray flatlands that TV viewers had seen in past Apollo coverage was a moonscape of extremes, a backdrop without earthly equivalent.

Astronauts Dave Scott and Jim Irwin landed a mile from the canyon and three from the nearest mountain. A short time later, during a “stand-up EVA” from the lunar module’s top hatch, Scott took a look around. One aspect of the place leapt out: it was relatively free of boulders and other obstructions. “Trafficability looks pretty good,” he told Houston. “It’s hummocky—I think we’ll have to keep track of our position. But I think we can manipulate the rover fairly well in a straight line.”

And so, the next morning, America watched over breakfast as the astronauts stepped onto the plain—more formally, and ominously, known as the Marsh of Decay—and released the mission’s star attraction from quadrant 1. Frank Pavlics and Sam Romano, at Mission Control as technical advisers, saw the rover unfold and drop to the surface. “We were all cheering,” Pavlics recalled. “I was sitting on needles. It was satisfying, and very exciting, to see the thing working like that.”

But then the moon buggy hit a few snags. It hung up briefly on the saddle linking it to the lander. The astronauts twisted and tugged until it came loose. A few minutes later, as Scott unfolded his seat, the Velcro holding it in place proved stronger than lunar gravity, and he almost yanked the entire vehicle off the ground. Then, as Irwin filmed him, Scott climbed aboard, eased the machine forward, and discovered that he couldn’t turn his front wheels. Irwin confirmed the bad news. “Got just rear steering, Dave.”

Their capsule communicator, or capcom—a fellow astronaut named Joe Allen, through whom Mission Control routed all messages to and from the crew—suggested a number of switch combinations on the control panel. “Still no forward steering,” Scott told him.

In Houston, Romano sat horror-struck. “I was sitting in the Mission Control Center, in the third row,” he told a documentary filmmaker many years later. “Dr. von Braun was in the fifth row. So when they said, ‘The front wheels are not steering,’ my God, I was very, very nervous. The back of my neck began to swell, get red. My ears were red.”

Pavlics, watching nearby, thought he knew what was up. A tiny component in the steering electronics, called a potentiometer, was failing to carry an electrical signal. “Sometimes the metal-to-metal connection in the potentiometer didn’t make contact, and that was happening there,” he told me. “So I suggested that they should exercise the hand controller, to move the two pieces together.”

On the Hadley Plain, Dave Scott waited for instructions. Would Houston scrub using the rover? If so, Apollo 15 was going to be far less ambitious than everyone had hoped. Steering with just the rear wheels was certainly doable, and Mission Control’s own rules for Apollo 15 allowed it, but NASA typically insisted on redundancy. Seconds passed before Allen told him, “Press on.” Pavlics’s fix would wait; the clock was running. Scott and Irwin hurried to attach the lunar communications relay unit, TV camera, and antennas and to load tools into the storage pallet behind their seats.

Irwin climbed on. “You really sit high,” he said. “It’s almost like standing up.” He reached for his maps and found that his pressurized suit bent so little that he couldn’t stretch that far. Minus Earth’s gravity and atmosphere, their suits were fatter and stiffer, and the astronauts’ lighter weight gave them less leverage. He fumbled with his seat belt. It wouldn’t close. “I think it’s too short, Dave.”

Scott came around the rover to help. “Yeah, sure is.”

“Don’t waste time on it,” Irwin told him. “I’ll just hang on.”

“No,” Scott said, making perhaps his wisest decision of the day. “We can’t lose you now. Got too far to go.” He got the belt latched, climbed back in, and buckled his own belt. “Okay, Jim, here we go.”

“Okay,” Irwin said, “we’re moving forward.”

“Whew!” Scott said. “Hang on!”

From the book ACROSS THE AIRLESS WILDS: The Lunar Rover and the Triumph of the Final Moon Landings by Earl Swift. Copyright © 2021 by Earl Swift. From Custom House, a line of books from William Morrow/HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.