You might have gotten an X-ray at the dentist’s or after a broken bone before—but that was child’s play compared to what they have at Menlo Park, California.

Nestled underground beneath Stanford University is the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), a powerful X-ray laser managed by the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. Since 2009, the particle accelerator has given scientists an unprecedented look at the molecular and atomic structure of matter by shooting electrons through a copper pipe and generating 120 X-ray pulses per second. It’s often considered the world’s most powerful X-ray as a result—and it’s about to get even more powerful.

SLAC is in the final stages of the LCLS-II upgrade project. Once finished, the accelerator will be able to generate a million X-ray pulses per second. To do so, though, the machine needs to be capable of superconducting—a term that describes the disappearance of electrical resistance—allowing the electrons to move even faster. The only way to achieve this is by making things very, very cold. That’s why the team installed a series of supercooling modules to a half-mile stretch of the accelerator, successfully bringing temperatures down to nearly absolute zero on April 15.

“Unlike the copper accelerator powering LCLS, which operates at ambient temperature, the LCLS-II superconducting accelerator operates at 2 kelvins, only about 4 degrees Fahrenheit above absolute zero, the lowest possible temperature,” Eric Fauve, director of the Cryogenic Division at SLAC, said in a press release. This would mean that parts of the X-ray laser would be colder than most of outer space and the universe.

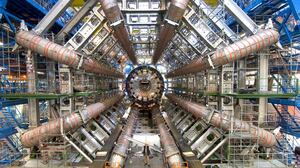

To hit the incredibly cold temperatures needed for superconductivity, the team outfitted the LCLS-II with two helium cryoplants, which cools helium gas down to its liquid phase a few degrees above absolute zero. This is similar to the superconducting cooling methods of the Large Hadron Collider, the world’s largest atom smasher in Geneva, Switzerland.

The accelerator was finally turned on on May 10. Now, the LCLS-II will be able to give scientists an even more precise look at molecules, observe rare chemical events, and directly measure the motions of individual atoms. It’s expected to produce its first X-rays later this year.

Researchers believe that the new insights could also lead to a wealth of scientific discoveries and technological developments. For example, the X-ray could help with the creation of new clean energy tech by allowing researchers to study soil, water, and air chemicals affected by climate change in minute detail. SLAC scientists are also using the LCLS to research new forms of photovoltaics and solar energy technology. All the research projects using the X-ray could also lead to new forms of computing as SLAC scientists develop new methods of data acquisition and storage.

“In just a few hours, LCLS-II will produce more X-ray pulses than the current laser has generated in its entire lifetime,” Mike Dunne, director of LCLS, said in a press release. “Data that once might have taken months to collect could be produced in minutes. It will take X-ray science to the next level, paving the way for a whole new range of studies and advancing our ability to develop revolutionary technologies to address some of the most profound challenges facing our society.”