There isn’t a more perplexing puzzle among all the stirring tales of American innovation than the one inherent in the story of the Wright brothers. As David McCullough says of them in his new biography: “They had no college education, no formal technical training, no experience working with anyone other than themselves, no friends in high places, no financial backers, no government subsidies, and little money of their own.”

What an inspiring text it seems—at first sight—for the triumph of self-reliance. In order to become the first men to make powered flights the Wrights intuitively worked their way to mastering four challenges that had defeated all their forerunners: how to control flight, how to build the first engine able to power flight, how to design the first effective air propeller—and, not the least of their astonishing breakthroughs, how to successfully pilot the machine they created.

And yet the Wrights flew right into a technological blind alley. They stuck stubbornly to a form of airplane that quickly became obsolescent. As a result, they failed to see and develop the full potential of their own amazing invention. It’s as though Steve Jobs, having delivered the original 1984 Macintosh, had stopped right there and said that as far as he was concerned, that’s it. Done

David McCullough doesn’t explore this puzzle but he does provide rich material to suggest how and why it happened, and it can be summed up in one word: France.

In 1908 Wilbur Wright arrived in Paris, preparing to demonstrate the latest version of the Wright Flyer, while his brother Orville remained in the United States to make similar demonstration flights to the U.S. military. Wilbur was to spend just over a year in France, during which he became a one-man flying academy, teaching French aviators how to fly and explaining the basic secrets of making an airplane controllable—something that the Europeans had failed to discover for themselves despite years of trying.

Control was the essence of the Wrights’ invention. On the way to achieving it, Wilbur had spent years watching and studying the miracle of a bird’s wings.

‘The birds’ wings” he noted “are undoubtedly very well designed indeed, but it is not any extraordinary efficiency that strikes with astonishment but rather the marvelous skill with which they are used.’”

His Eureka moment came with the observation that a bird adjusted the tips of its wings so as to present the tip of one wing at a raised angle, the other at a lower angle. ”Learning the secret of flight from a bird was a good deal like learning the secret of magic from a magician.”

That flexing of the wing tip was the path to what all previous aviators had failed to achieve, lateral control. And it was the degree of lateral control that the Wright brothers achieved that astonished the Europeans when they saw it.

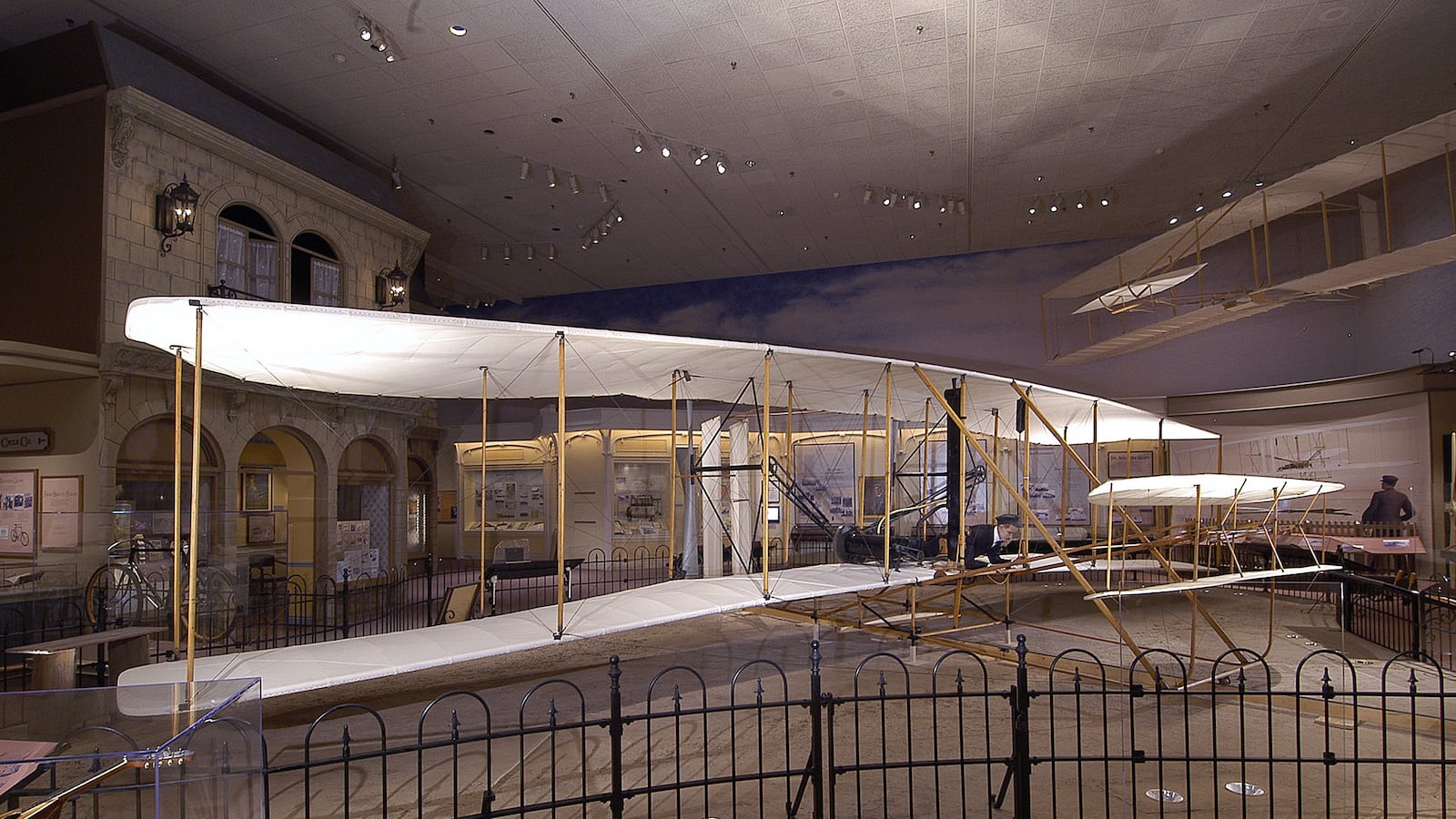

The Wrights twisted, or warped, the Flyer’s wing tips to make the machine stable as it turned. It was attempting to make a turn that had wrecked many previous attempts to fly. Of all the devices the Wrights patented, this was the most decisive. Not only did the Wright Flyers make a turn, they could fly in circles and return to their starting point, which amazed those who saw Wilbur’s first flights at Le Mans in France.

“We are children compared to the Wrights.” one French aviator said. Louis Bleriot, who would himself become a formidable aviator, saw exactly the significance of what he witnessed: “I consider that for us in France, and everywhere, a new era in mechanical flight has commenced.”

In Paris Wilbur was treated as a world celebrity, installed in the luxurious Hotel Meurice, “the hotel of kings.” An ascetic by nature, Wilbur enjoyed the comforts but, as McCullough makes clear, he was not softened by the experience. He had what McCullough astutely describes as “a truly exceptional capacity of mind.” The ascetic turned out also to be an aesthete. Visiting the Louvre he liked the Rembrandts, Holbeins and Van Dycks, but Titian, Raphael and Murillo not so much. And he was disappointed by the Mona Lisa.

And, to the French, Wilbur appeared to be as enigmatic as Mona Lisa’s smile. Leon Delgrange, who was not only a French aviator but a sculptor and painter who wrote about Wilbur for Le Figaro declared with Gallic despair, “Has he a heart? Has he loved? Has he suffered? An enigma, a mystery.” Another Frenchman who traveled to Berlin by train with Wilbur was amazed when, riding through Belgium, Wilbur explained the historical significance of a town called Jemappes where France won a turning-point battle against Austria in 1792.

The reality was that Wilbur was a polymath whose curiosity knew no bounds and whose intellect processed information with an intensity that his outward emotions lacked. This type of personality was confusing to the “continental” mind but explicitly American in the degree of its self-reliance.

And how self-reliant it was. Some of the most gripping passages in the book describe the fortitude of the brothers while they lived for months among a fishing community on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, a world of medieval rigor and remoteness. Of course, remoteness in much of the world would eventually come to be eliminated for ever by their creation.

Their first flight in 1903 at Kill Devil Hills, near Kitty Hawk—and three other brief flights—showed the Wrights the way forward but they also revealed stubborn problems that they had to solve by assiduous testing and development. In the course of this testing during 1904 they made 105 flights, improving the machine’s performance all the time, and then, in 1905, they produced what was called the Number 3 Flyer. This was no longer experimental but practical and the basis of the world’s first really reliable flying machine.

Strangely, this surge of invention was followed by hiatus. For two and a half years, between October 1905 and May 1908 the Wrights did not leave the ground. They were almost overwhelmed by the challenge of getting somebody—anybody—to understand the significance of what they had achieved.

Two weeks after the first flight, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge passed to the War Department a report of their achievement at Kill Devil Hills. Then, and for the next year, the War Department took no notice and remained uncomprehending that a machine that would revolutionize warfare had just been invented by two bicycle makers in Dayton, Ohio. “Those fellows are a bunch of asses” said one of the Wrights’ supporters of the officials in Washington.

The French were not so dumb. In March 1906 a delegation of French military experts arrived in Dayton. They wanted to make a deal to produce Flyers in France but, after months of negotiations, no deal was done. The Wrights were very aggressive and possessive about their patents and hard to satisfy. Astonishingly, they had spent only $1,000 of their own money to get from the kites to a successful powered flight and they resisted offers of funding from some of the famous robber barons of the age, determined to remain independent of big money and in no hurry to get rich.

Instead of handing over their design to the French they ended up using France as a showcase to stake their claim of being not just the pioneers of aviation but the unique owners of the science that guaranteed consistent and safe flying. However, their confidence in their exceptionalism was misplaced. Between the summer of 1908 when Wilbur first flew at Le Mans and the summer of 1909, the Europeans passed from awed spectators to serious competitors. In 1908 there were fewer than half a dozen airplane builders in the Paris area. By the middle of 1909 there were fifteen.

On July 25, 1909 Louis Bleriot flew across the English Channel, 23 miles in 20 minutes. It was world shattering news with obvious implications. Orville marveled at Bleriot’s airmanship but belittled the machine “over which he had so little control.” Orville failed to see that Bleriot’s machine, as frail as it might have been, was a precursor of the ultimate form of the airplane: a monoplane with a fuselage and an empennage (horizontal and vertical stabilizers at the tail) and not, as were the Wright Flyers, a direct derivative of the box kite with a horizontal stabilizer at the front, not the back.

And then, confirming how much Europe had learned in one year, came the world’s first great aeronautical pageant, staged in Champagne country, La Grande Semaine d’Aviation at Reims. It opened on Sunday August 22 with a grandstand packed with 50,000 spectators. By its final days, a week later, the crowds had grown to 200,000. Twenty-two pilots flying 22 airplanes competed, flying higher, farther and faster than anyone had and breaking every record set by the Wrights in the past year. And the biggest winner was an American named Glenn Curtiss who won the prize for speed and would later emerge as one of the most accomplished airplane builders in the U.S.

On September 29 Wilbur, back in America, caused a sensation by circling the Statue of Liberty in a Flyer. But the nation that donated that great symbol of liberty had, by then, already surpassed the U.S. as the primary incubator of the age of aviation.

This makes McCullough’s story all the more poignant because he is so brilliant at recreating the improbable world from which the Wrights’ invention emerged. Indeed, it is a story that refutes the cosmopolitan arrogance of the time that regarded a city like Dayton at the turn of the 20th century as a provincial backwater. While all the money and the glamor of Edith Wharton’s Gilded Age was consuming the New York newspapers, the residents of Dayton were busy, largely unnoticed, inventing things—measured by the number of patents registered per population Dayton was first in the nation, driving the advance of industries as diverse as railroad cars, cash registers, sewing machines and gun barrels.

The Wrights’ path to their invention began in the summer of 1899 in a room above their bicycle shop on West Third Street in Dayton. Using split bamboo and paper they built a kite—or so it looked. But this simple rig included their first use of wing warping as a means of control. By the fall of 1901 they had advanced so far in their understanding of aerodynamics that they built themselves a small-scale wind tunnel. It was a wooden box six feet long and 16 inches square, with one end open and a fan at the other end powered by a very noisy gas engine (because there was no electricity in their shop).

In all but his name there was actually a third Wright brother at work in Dayton whose practical genius was equal to theirs, their house mechanic named Charlie Taylor. It was Taylor who built the engine for the Flyer. And here it is important to note that the lack of a viable source of propulsion had held back aeronautics for nearly a century.

The general principles of aerodynamics were first understood and established early in the 19th century by Sir George Cayley, one of those gentlemen amateur scientists that England seems to have produced regularly since the Industrial Revolution. Cayley identified the four key forces at play in flight: weight, lift, drag, and thrust. Crucially, he divined that the invisible force of lift was produced by a wing with a cambered cross-section. He got as far as building a glider that (briefly) carried a man. But there was no machine to produce the thrust for powered flight—the steam engine was way too bulky.

That changed, potentially, with the coming of the internal combustion engine and the first cars. But car engines were still too heavy and it was Charlie Taylor who solved that problem. He went to the fledgling Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA) and ordered an aluminum engine block. Taylor’s only previous experience of any relevance was having once fixed a broken car engine. Now, working in the Wrights’ shop with the same metal lathe and drill press used for building bicycles he produced the world’s first airplane engine in six weeks. It weighed only 152 pounds and delivered 12 horsepower. It had no spark plugs and a gravity-fuel system—crude, but it worked. That engine, combined with the propeller that the Wrights had formulated after much study, delivered the fourth force needed to take man into the sky—thrust.

Charlie’s engine was noisy, very noisy. The first passengers who flew with the Wrights complained that even after a short hop they were deaf upon landing. But on December 17, 1903, when Orville flew the first Flyer on the Outer Banks for 120 feet in 12 seconds it was not noisy enough to get any significant attention from the outside world—a world that this single event would so profoundly change.

The news did not travel fast nor was its import grasped when it was received. The first to get word that on the fourth flight of the day Orville had flown for 59 seconds was the city editor of the Dayton Daily Journal. His response was: “Fifty-seven [sic] seconds, hey? If it had been fifty-seven minutes then it might have been a news item.” There was no word of it in the next day’s issue of the Wrights’ hometown paper. Not so the Norfolk Virginia Pilot, which ran a banner headline on the front page across seven columns: “Flying Machine Soars Three Miles in Teeth of High Wind Over Sand Hills And Waves At Kitty Hawk On Carolina Coast.” Never mind the greatly inflated facts—the Pilot knew a scoop when it saw one.

Nonetheless, when garbled versions of the same account appeared in the Chicago Tribune, the Washington Post and the New York Times little happened as a consequence. Six months later, as the Wrights were making flights of more than 1,000 feet and managing for the first time to fly in a complete circle at a place called Huffman Prairie near Dayton not one local reporter bothered to visit.

But their feats were finally seen by someone who realized how consequential they would be.

McCullough has great fun describing this unlikely but sentient witness to momentous history: he was a motoring enthusiast named Amos Ives Root who produced a journal called Gleanings in Bee Culture and it was he, of all people, who recognized the genius of the Wrights.

“These two brothers have probably not even a faint glimpse of what their discovery is going to bring to the children of men.” With Root’s stirring words the Big Picture was at last relayed way beyond the normal readership of Gleanings in Bee Culture.

And an essential part of that Big Picture was the airplane’s potential as a weapon of war. The strategic result of the Wrights’ invention is beyond the scope chosen by McCullough for his biography, which is a pity because the Wrights were part of a comprehensive American failure to understand air power in its infancy.

In Washington the war department finally asked the Wrights to conduct flight trials necessary for them to assess the early Flyer, and while Wilbur was in France Orville had demonstrated how reliable it was. The U.S. Army established an Aeronautical Division in 1907 and in 1909 they bought their first Wright machine for $25,000. Congress, however, was not persuaded of the value or importance of air power. The first funds allocated specifically for military aviation in 1912 amounted to only $125,000.

There was no such myopia in Europe. In 1911 the French government appropriated $1 million for its military’s air arm. In France, Britain, Holland and Germany funds were poured into research and development. A first generation of faster, nimble warplanes emerged. The First World War accelerated European aviation technology while the U.S. was left with a small fleet of machines that had advanced little beyond the early Wright models. The last Wright airplane sold to the military was delivered in May 1915 and dropped from the inventory a month later.

When the U.S. entered the war in 1917 it had fewer than 200 primitive machines used for artillery observation that their pilots called “flaming coffins” and one airplane engine in development that arrived too late to be of any use. To build an air force capable of front line combat the war and navy departments ordered 3,000 models of both British and French designs.

Long before the war the Army had complained that the Wrights had a “hidebound determination” to stick to their original kite-based configuration of biplane and control surfaces at the front instead of at the back of the machine. It was true. They had turned a kite into an airplane but the vestiges of the kite remained, while the Europeans rapidly developed the far more effective wings-fuselage-tail configuration.

However, to speak here of “the Wrights” as a continuing entity is misleading because Wilbur died of typhoid on May 30, 1912 at the age of 45 and therefore it is hard to know if he would have realized that a new approach was needed.

It was never easy to divine the distinct talents of each brother because they were so obviously mutually reinforcing of each other’s gifts, and admitted no ascendancy of one over the other. Judging by the cultural depth revealed in Wilbur by his experience in Paris, and the confidence he showed in his own judgments of art, he seems to have had a broader intellect than Orville but when it came down to the brothers’ astounding ability to create a body of scientific knowledge empirically there was not a sliver of light between them.

After Wilbur’s death Orville was sucked into a long and consuming bout of patent suits that were not settled until 1914 (all in his favor). Then he sold the factory and patent rights to a syndicate of financiers and banks. In 1916 the Wright factory was merged with the Glenn L. Martin Company to form the Wright-Martin Aircraft Company. Orville died in 1948, aged 77, leaving an estate worth $10.3 million in today’s dollars. No airplane manufacturer ever made a fortune to compare with the 19th century robber barons—or today’s masters of the universe.

However, what seemed for the U.S. an ignominious audition in the aviation industry concealed the chrysalis of a far more impressive future. In 1917, on the banks of a filthy little river on the outskirts of Seattle a new airplane company was set up in a red barn, initially producing a few wooden and canvas seaplanes. Its owner was a well-heeled and patrician young man named William Boeing. Barely noticed in Washington, the company slowly grew and attracted some far-sighted engineers.

At the same time, the airplane engine that arrived too late for use in the war, the Liberty, demonstrated an American understanding of mass production that Europe could not match—in one year, between 1918 and 1919, more Liberty engines were manufactured than Britain had produced in the entire war.

Within little more than a decade the unique American ability to industrialize a new technology revolutionized aviation. While the politicians in Washington continued to retard the development of military aviation, the first generation of airline entrepreneurs provided the funds for combining mass production with another innovation in which American skills were superior: the all-metal airplane.

The future of the business that began in a room over a bicycle shop in Dayton did, after all, belong to America.