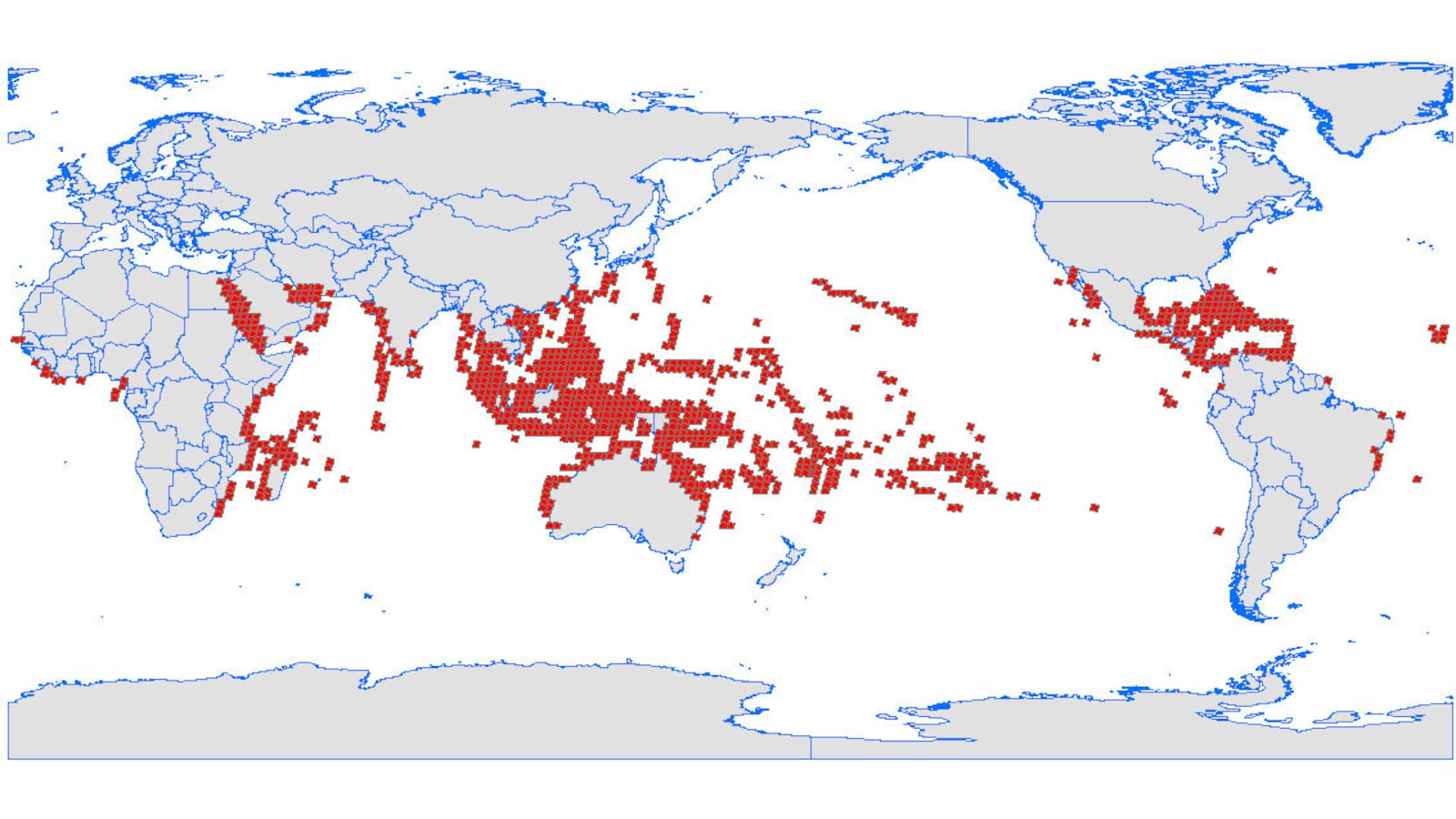

There is no comprehensive map of the world’s coral reefs. And that’s a problem because these ecosystems are some of the most important on the planet: they house a huge percentage of the ocean’s species, they absorb 70 percent of the wave energy coming to shore, and they attract $37 billion worth of tourism every year.

They are also in grave danger. As the climate warms, the oceans are absorbing much of that heat—which in turn makes the water more acidic, which causes coral bleaching (a state that makes them vulnerable to dying off). To better understand the state of the world’s coral, the Nature Conservancy, a non-profit that works to preserve land and water under threat around the world, is using a new technology to image and map all the coral reefs in the world.

“We are always crying out: corals, corals, corals are in bad shape! But we don’t have very good maps. When you see a map it’s the kind of map you use for navigation so ships won’t run aground. They look like little clouds. But when you go diving you see a coral reef is way more complicated than that. Information at that level of detail only exists when scientists go diving, do transects, and measure the field. But we are limited by our diving capabilities and time,” says Luis Solórzano, Executive Director for The Nature Conservancy in the Caribbean.

Starting in the Caribbean, the goal is to create a comprehensive baseline of the world’s reefs. Specifically, they want to map which species live in each reef so they can better understand which ones are surviving the warming climate and which ones are dying off. They are doing this with a special technology developed by Greg Asner. Called the Carnegie Airborne Observatory (CAO), the device has four sensors: two different spectrometers, a camera, and a wLIDAR scanner. Flying the CAO over the corals, Asner is able to capture the chemical fingerprint and composition of what is living below the surface of the water.

Once the data is collected, it is compared to satellite images, drone footage, drop cameras (which take underwater images), and data gathered by SCUBA divers. Solórzano says that the divers, specifically, can help pair species names with the chemical signatures picked up by the CAO. “When you go down there and measure it exactly, you can identify what different signatures you’re seeing: that’s sand, that’s a reef covered by algae,” he says. In this way the technology can be trained to identify exactly what it’s seeing.

The Caribbean is just the first step in a series of flights that will map and categorize reef systems all over the world. Solórzano says this should be accomplished in no more than two-and-a-half to three years. The maps will then be used to create plans for preservation, protection, and restoration of reefs. “Imagine if you need to design network of marine protected areas. That map is essential,” he says.

He also notes that in the Caribbean, the plan is to begin physically restoring coral reefs by using the maps to show them which corals are most stable in the changing ocean. Once the Caribbean map is made, they will begin taking corals from the water, growing them on land, reproducing new ones in their nurseries, and then returning them to ocean. “You want to put back into the water those that are resistant. We’re going to do that for the first time,” he says. “We’re are learning how to do it.”

Restoring corals on land and returning them to the sea isn’t exactly a new idea. The University of Miami, for example, has been running The Coral Restoration Project, in which they’re using nurseries to propagate staghorn coral, since the 1970s. But it is a program that is gaining steam—and becoming increasingly more essential as scientists are beginning to suggest that the die-off of coral reefs around the world could be indicating an extinction event. “Corals are one of the most important systems in the global oceans. Globally they provide food and livelihood to more than 500 million people,” Solórzano says. “They have gone through global extinctions in the past and it seems like we're about to push them to another.” But hopefully with the combination of our new global maps and restoration projects like those from the Nature Conservancy we can keep them healthy for as long as possible.