Religion has never been absent from American politics.

Presidents Democratic and Republican alike invoke divine calling when they take us to war. The House and Senate have chaplains. We swear in court with our hands on holy books. And in ordinary conversations and public comment alike, many Americans explain their political ideas, at least in part, with religious language—touting legislation or defending voting decisions with snatches of biblical text and chains of logic that begin with God.

But the conviction that politics is a secular environment, and religious reasoning an invasive species, is increasingly commonplace.

Its roots are in the Enlightenment, but as a rising norm in some quarters of American politics, it’s only a few decades old. In 2006, then-Sen. Barack Obama decried “liberals who dismiss religion in the public square as inherently irrational or intolerant,” arguing that “we make a mistake when we fail to acknowledge the power of faith in people’s lives—in the lives of the American people—and I think it’s time that we join a serious debate about how to reconcile faith with our modern, pluralistic democracy.”

But 16 years later, insofar as the American polity has shifted on this issue, it’s in the opposite direction of what Obama urged. That’s been particularly obvious this summer, after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. Combined with shifting religious demographics—Christian affiliation, belief in God, and membership at houses of worship are all at record lows—it has subjected public mention of the divine to intense debate.

That disagreement goes beyond the bristling in familiar pro-choice slogans, like “keep your rosaries off my ovaries” or “keep your theology off my biology.” The contention now is not merely that sectarian legislation and favoritism are unconstitutional, which certainly they are, or that a religiously motivated pro-life position is wrong. Rather, it is that speaking of religion in politics—providing a religious rationale for any policy stance, or at least a disfavored one—is itself illegitimate, maybe even a violation of the Establishment Clause, the First Amendment’s prohibition of a state church.

The Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe “ignores the constitutional principle of separation between state and church,” charged the Freedom from Religion Foundation in June. Officials who cite their faith as the source of their pro-life stance “aren’t even trying to hide the religious motivations for their actions,” complained a May article at Religion Dispatches, “which would certainly make [their abortion policies] unconstitutional under any reasonable interpretation of the Establishment Clause.” A viral tweet thread inspired by the end of Roe contended that though religious people can believe whatever they like “in the confines of [their] skull[s],” to “act like it’s true” is indecent and impermissible. Religion is cast, in the phrase of Yale University theologian Miroslav Volf, as “a pernicious social ill” which “it is necessary to weaken, neutralize, or eliminate…outright as a factor in public life.”

Demonstrators gather in front of the U.S. Supreme Court as the justices hear arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health on December 1, 2021 in Washington, DC.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty ImagesIt’s in this context that journalist Matt Yglesias expressed frustration on Twitter in August with religious people “pretend[ing] not to have” theological motives in the abortion debate when it’s obvious that they do. And Yglesias is right that this pretense happens—but he’s missing, I think, the rising social pressure on religious Americans to do exactly this kind of dissembling.

Before we turn to that pressure, though, it’s important to consider why religious reasoning deserves a place in politics in a society like ours: religiously diverse and constitutionally forbidden from establishing a state-backed faith.

First and foremost, the impulse to oust religious language from the public square, as Volf writes, is not only misguided but impossible to implement in any formal sense without encroaching on other First Amendment rights to free speech and free exercise of religion. For many people of faith, religion cannot be confined to a separate realm, cordoned off from the shared space in which we make decisions about how to live together as a society.

In fact, for some Americans, religion is the sole context outside politics where they regularly encounter ultimate ideas like justice, mercy, human nature and personhood, the purpose of the state, the directionality of history. You may run into them all the time in college or if you’re terminally online or if you work in a few urbanized, educated industries, like journalism. But for the average busy adult, church may be the primary or only opportunity to consider questions about what we owe to one another. Religion is the main fund of vocabulary and ideas to engage in politics at a level more thoughtful than the beer question, to meaningfully contribute to the discourse. For these Americans, referencing religion when talking politics is normal, intuitive, maybe inevitable.

It can benefit the whole body politic, too. Religious belief can bring unique insight—some of the most important voices opposing Christian nationalism are Christians making explicitly Christian arguments—and can build a powerful moral case for political change, as Rev. William Barber II does in the Poor People’s Campaign.

Obama pointed to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “summoning of a higher truth” which “helped inspire what had seemed impossible.” I’m not sure King’s strategy would work as well today, but religion’s emphasis on tradition and wisdom, hard won and passed down through generations, is valuable in our ethically unmoored, historically naïve, and newsfeed-driven age.

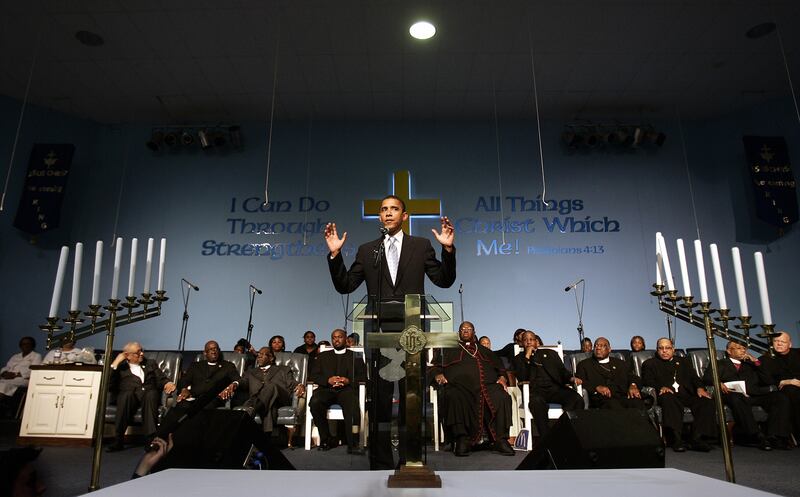

Sen. Barack Obama makes remarks at St. Mark Cathedral 15 January, 2007 in Harvey, Illinois. Obama spoke to the congregation on the birth date of the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Jeff Haynes/AFP via Getty ImagesMoreover, if we discourage political candidates from speaking openly about their faiths, we might not like what we find after they’re installed in office. Do you want to elect a Marjorie Taylor Greene unawares? Explaining how religion informs one’s politics is a type of honesty, after all—and I suspect, to some degree, the critics realize this. That Religion Dispatches piece objected to Christians not “trying to hide” their motivating faith, which recognizes the religious thinking is there, even if it’s not verbalized. Why must it go unspoken?

It’s one thing to say religious explanations are propping up bad policy and shoddy legal reasoning, or that religion itself or its nationalist syncretism is factually and ethically lacking, or that Americans who can only explain their politics in terms of their religion are brainwashed or ill-educated. Those may or may not be fair critiques, but they are fundamentally different critiques than the demand for public silence on religion. There are plenty of ways to push back on bad takes without telling religious people to shut up about the God stuff.

Perhaps it is perceived that speaking religiously in politics is an act of power and privilege, a right only the Christian majority claims. There’s merit to that charge insofar as Christians attempt to deny public expressions of religion to Americans of other faiths. And this does happen: Fox News host Jeanine Pirro, a Catholic, in 2019 attacked Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) for her practice of wearing a hijab, scurrilously suggesting this religious expression showed infidelity to the Constitution. I’ve written here of conversations “at church” because Christianity is the religion generally at issue in this debate, and it’s also where my own experience lies. Yet the same defense of religious reasoning in public can and should be made for every faith in America.

Or perhaps faith should be quiet because this language feels irrelevant or outright alienating for those who don’t share the same beliefs. Perhaps religious people should strategically translate their ideas into more neutral phrasing if they want to persuade people and effect political change. Stop trotting out the Bible verses and explain your policies in terms that do not stop the conversation.

Rep. Ilhan Omar speaks during a press conference at a memorial for Daunte Wright on April 20, 2021 in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota.

Stephen Maturen/Getty ImagesThat might well be good advice, and I often translate my own ideas to make them accessible to a wider audience. When I write about foreign policy, for example, I speak in secular terms of prudence, national interest, and humanitarian effects, leaving unmentioned the Christian pacifism that undergirds my positions. I look forward to the day when God “will settle disputes for many peoples. They will beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not take up sword against nation, nor will they train for war anymore”—yet I don’t push policymakers to prefigure the peace of the new creation in U.S. foreign affairs. I talk about blowback, deterrence, risk calculations, diplomatic tactics, and the like, because I know this is the more persuasive language in that milieu.

But I have the luxury of doing this for a living. Most people don’t, and we can’t expect them to craft arguments like someone whose whole career is crafting arguments any more than I should be expected to fix my own car with the skill of a mechanic. Laws must be religiously neutral, but as Obama noted, “Americans are a religious people,” even given our recent demographic shifts. Living in a democracy means hearing from the demos, and most of the demos remains religious.

Indeed, for many religious people, excising or translating the religious inspiration for their political conclusions simply does not make sense. It feels like a lie, or self-sundering. To mentally adhere to a religion without acting like it’s true, to confine religious belief to the skull while performing laïcité in public—this is an unintelligible demand. It runs afoul of the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause in the name of protecting its neighbor, and its neighbor does not need protection from people of faith speaking our minds.