Opinion

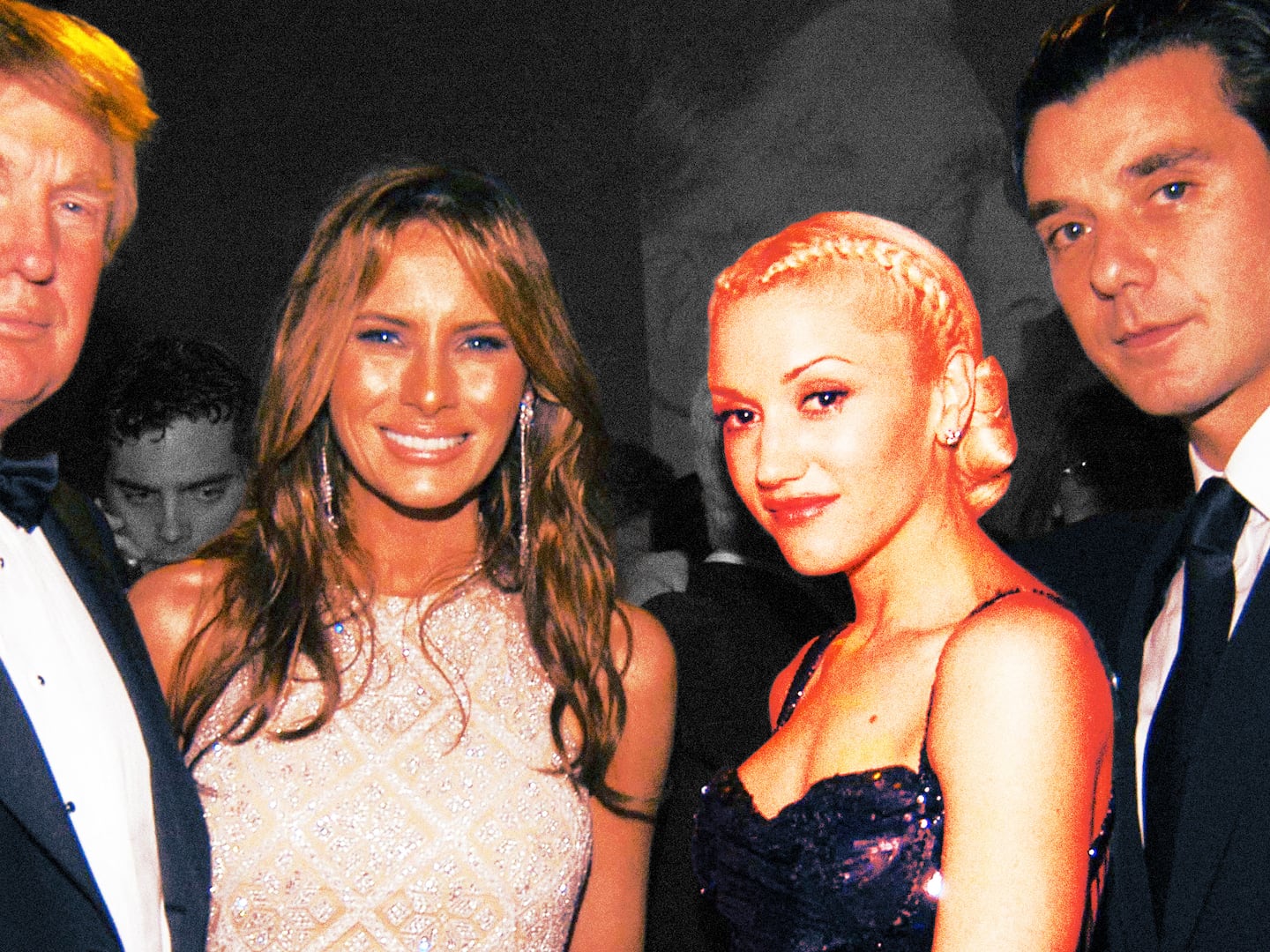

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty

These Under-the-Radar Rulings in the Stormy Daniels Hush Money Case Are Really Bad for Trump

RUH-ROH

The brief delay in the New York trial is just a small victory for Trump. The really consequential stuff hasn’t gone his way lately.

opinion

Trending Now