Most Americans are oblivious to the post 9/11 conflict. Some know it as a family war.

As David George remembers it, he was serving at a tiny U.S. military base in Afghanistan when his eldest son reached out from Florida to tell him he was planning to visit a recruiter.

Joey George, a 20-year-old Army reservist, said his father is one of the reasons he signed up to fight in America’s long war on terror.

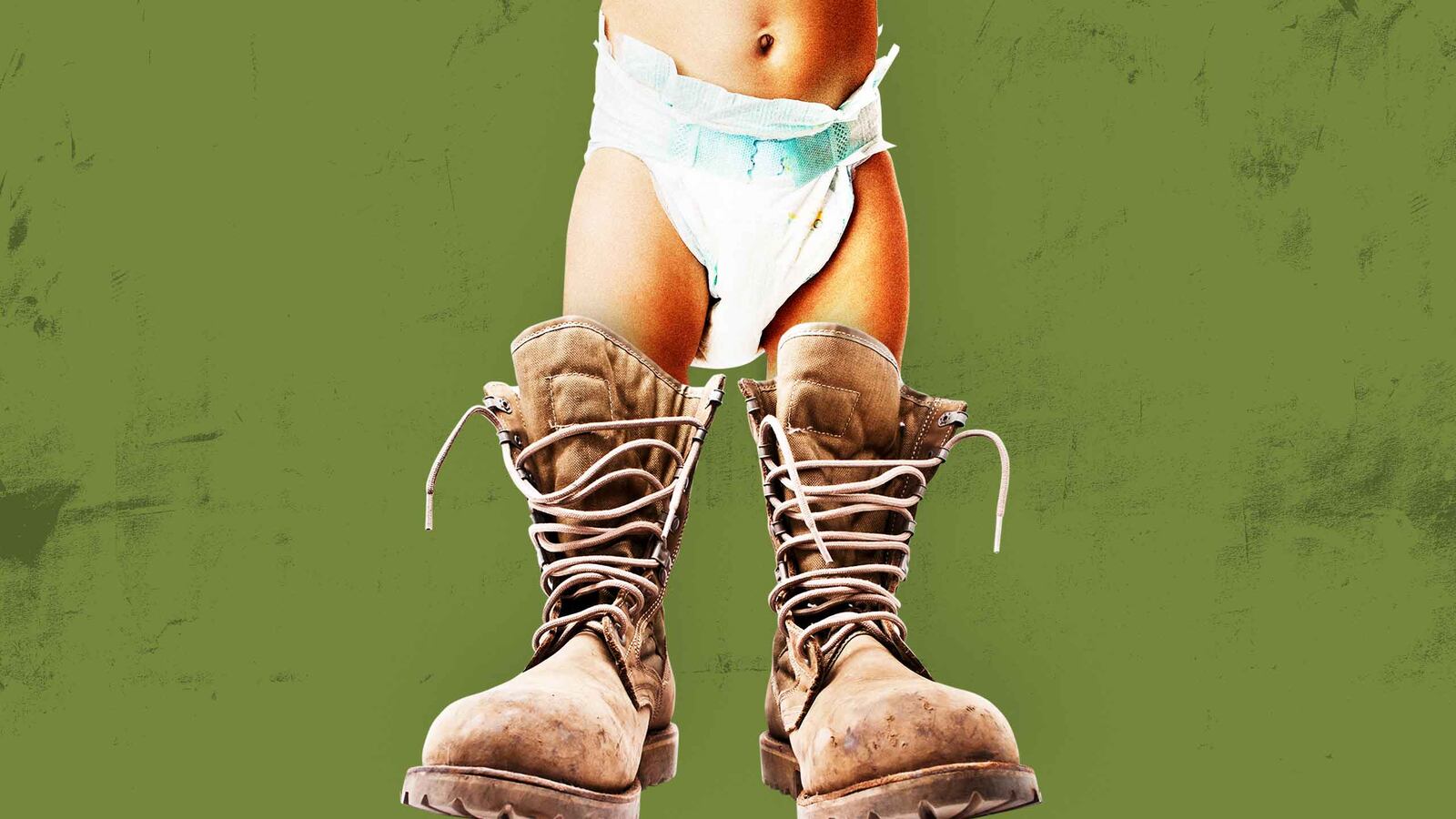

It’s not unusual for several generations of one family to serve. The grandsons of World War I veterans fighting in World War II. The granddaughters of Vietnam veterans deployed to Afghanistan. But America is now seeing children preparing to deploy to their parents’ battlefields. It is a measure both of how protracted the war on terror has been, and of how few are fighting it.

“We now have an entire military subculture carrying this burden for the majority of Americans who do not even know about it,” said Dr. Edward Tick, a psychotherapist based in New York state who has worked with traumatized vets from several wars since the 1970s and written extensively about what he sees as a growing and worrying military-civilian divide.

As Pew researchers wrote after conducting a survey marking the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks in 2011, the conflicts waged since the Twin Towers fell “have been fought exclusively by a professional military and enlisted volunteers. During this decade of sustained warfare, only about 0.5 percent of the American public has been on active duty at any given time.”

Mark Rodriguez, an Iraq veteran who now has a daughter in the military, said civilians have told him: “'The war is over because Osama bin Laden is dead, Saddam is dead.' A lot of people don't realize that soldiers are still in Afghanistan. A lot of people really don't know.

"It does surprise me in a way. You get around a military base, everybody understands there's a war going on. They see the coffins coming back. They see their friends preparing to deploy. I think people should know. I think people should understand there's a war going on.”

He worries that soldiers returning from battles no one acknowledges may feel isolated. More awareness among the general public could create a unity and patriotism Rodriguez feels America is missing.

Rodriguez, unhappy in college, visited a campus Army recruiter after growing up hearing his grandfather’s Vietnam war stories.

“I knew that if I didn’t do something different from what I was doing I would be nothing,” he said. “I just saw (the Army) as a good way to get a start.”

Rodriguez joined the Army in 1989 and deployed to Iraq in 2006 where an explosion ended his military career. Just then his daughter was beginning hers.

Brittany Rodriguez, who grew up in Germany and at various military installations along the East Coast of the United States, had been in the Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Program in high school, when her father was in Iraq. She went on to ROTC in college in Kentucky. Her father said he encouraged her without imagining the war in which he fought would still be going on when she was ready to fight. He knows she wants to deploy. And though he worries, he believes she should.

“You shouldn’t be in something and try to get around the hard stuff,” he said. “If you’re going to be a leader, you should lead from the front.”

Since graduating from college five years ago, his 26-year-old daughter has been traveling from her base at Fort Bragg as a contractor teaching command system operations to soldiers across the country. The military intelligence specialist has reserve training a weekend a month and two weeks a year. Deployment, she said, is “something that can happen at any time,”

She said her parents and other military families she knew growing up gave her a sense of purpose other young people may lack.

"What's your why? Why am I living? It's for the friends who can't anymore. I have friends who have been injured and I know people who have passed away in war."

Listening to Brittany Rodriguez speak with commitment and confidence, it is easy to imagine what people like Ronie Huddleston were like when they were young recruits.

“You survive so many things, you start to think you’re indestructible,” said Huddleston, who spent two decades in the Army. “I always thought I would come home okay. I never thought that I’d be taken out with an IED,” or improvised explosive device.

Huddleston, who also fought in the first Gulf War to oust Iraq from Kuwait, was injured by a bomb in a 2005 deployment to Iraq, leaving him with traumatic brain injury and PTSD. He has since devoted himself to helping military families. He coaches peer mentors to combat suicide among veterans and runs retreats for a Colorado-based organization called Project Sanctuary that helps military families from across the U.S. strengthen bonds that can be strained when a parent has been deployed.

Huddleston takes some comfort in the idea that most Americans know little of war. If they did, he said, they might become inured to violence.

“I think civilians have just as vital and important a role to play as the military does,” he said. “The men and women who get up every day and go to jobs they might not like. If it wasn’t for the civilian population, the military couldn’t do what it does.

“I don’t think the American people need to know what we do to make them safe. I don’t want to have the horrors in my head either.”

Now Huddleston is contemplating the possibility his son will share those horrors. Huddleston rolled through Mosul with the 3rd Ranger Battalion. His 19-year-old son got orders to deploy to Mosul after joining the Army upon graduating from high school and following his father into the infantry.

“I couldn’t be more honored that my son is following in my footsteps,” Ronie Huddleston said.

But “I wish I could say I could die without having taken a human life. But I can’t,” Huddleston said. “I guess that’s the biggest thing that scares me for my son. He’s starting off very young going to war. So he’ll be toting that baggage for a very long time.”

In the past, old soldiers might divulge their worst war stories only with comrades who had shared their experiences. Now, those comrades could be sons and daughters.

Ronie Huddleston said his son, who has volunteered at Project Sanctuary retreats for military families, will “have something that I didn’t, and that’s a father, a parent, who’s been through the same and is willing to talk about it. Talk is key. He’ll have someone to talk to.

“He saw the changes in me coming back from Iraq. He saw the true impact of war on me. But he also saw me come through that. He’s seen me learn to live with PTSD.”

David George believes his absences from home during deployments in Iraq as well as Afghanistan shaped his children back in the military community of Fort Walton Beach, Florida.

“I think, especially for my eldest son who’s in now, it gave them an inside view of the military. Seeing guys do stuff that no one else wants to do. It instills a respect (for the military). Not that non-military kids don’t have the respect. But they don’t have a front-row seat.”

David George has more than once seen two generations of the same family together in a Guard unit. He did not object when his son said he wanted to serve. He is proud of his choice.

“He’s what a soldier looks like, acts like. I see great things for him in the future if he decides to stay in.”

He does worry about what it will be like for his son to come home from battle to a nation that seems oblivious to the sacrifices fighters are making. David George hopes civilians can muster a welcome that will make reintegration easier, especially for those suffering from anxiety, depression or PTSD.

“I guess the best thing anybody can do is just stay informed, know what the guys and gals are going through and what it’s like to come home,” he said. “The best thing to do to help is listening.”

Pollsters for the Washington Post and Kaiser Family Foundation found in a 2014 study that more than four in 10 Iraq and Afghanistan vets were children and half were grandchildren of vets of other wars. Indeed, David George’s grandfather was a sailor during World War II who later served 20 years in the Air Force. David George’s father was also Air Force.

“And I went Army,” he said, adding he was drawn in part by the programs that helped young people complete college when he joined the Army National Guard right out of high school in 1989.

He completed his guard commitment and started working in and owning restaurants. Then came 9/11 and the U.S. attacks on Afghanistan and Iraq.

“The war was just dragging and dragging,” he said.

Even though he was in his 30s and had a young family, he felt his country needed him. Perhaps it was his family’s legacy of service. He returned as a reservist in 2007 and trained to be a chaplain’s assistant, whose duties include coordinating counseling and services. He had served in his church’s men’s ministry and wanted a role in which he could “take care of soldiers.”

David George was deployed to Iraq in 2008. For a year he was based at Camp Bucca, a detention camp that was little more than a collection of fences and tents in the desert.

“We used to joke that the Marines would bring in a whole town just to get one person,” he said. “Maybe some of the people in there shouldn’t have been there. But a great number absolutely should have been.”

When he left for Iraq, his six children, understood where he was going any why in ways as varied as their ages, from a 14-year-old daughter to twin six-year-old girls. An eight-year-old son asked his father to bring back “some blood” if his father killed any terrorists. Joey, then 12, asked him to just come home.

“One of them wanted me to bring back the blood of the enemy. The other one wanted me not to die,” David George said.

By the time Joey was a junior in high school he was thinking seriously about becoming one of them. His best friend from high school also joined right after graduation, choosing the Marines.

Joey is not sure when he will be deployed. In the meantime, he’s studying civil engineering at the University of Central Florida in Orlando and training one weekend a month and at least two weeks a year as a combat engineer at his reserve station in Tallahassee.

While many fellow students in Tampa strike Joey as “left-wingy,” he has found comrades at his university’s veterans support center. He says he looks to the model his dad offers of having a tight group of friends who have shared his experiences as a support system to see him through any post-deployment difficulties. Joey George does not expect many other young people to understand his choices.

“If people don’t want to be concerned about world events, perhaps they … should just let the people who are actively concerned worry about things,” he said, making it clear he places himself firmly in the latter category.