When you watch a video of a magician performing a trick for a baby, you see a hilarious meme. But behavioral development researchers see something different: Evidence that children have an intuitive sense of physics.

Susan Hespos, an infant cognition researcher at Northwestern University and Western Sydney University, frequents magic stores to look for new ways to pull off the illusions used in her behavioral research.

“I'm often trying to create magic for babies,” she told The Daily Beast.

Her research engages with a longstanding nature versus nurture debate within behavioral development. In other words, how much of our perception of the world is learned, and how much is innate?

A perfect experiment, Hespos said, would be to raise groups of children on Earth where gravity dictates how objects behave, and in outer space where it does not.

She said she’d love to know the results of such a trial, “but I'm never going to do it with my kid.”

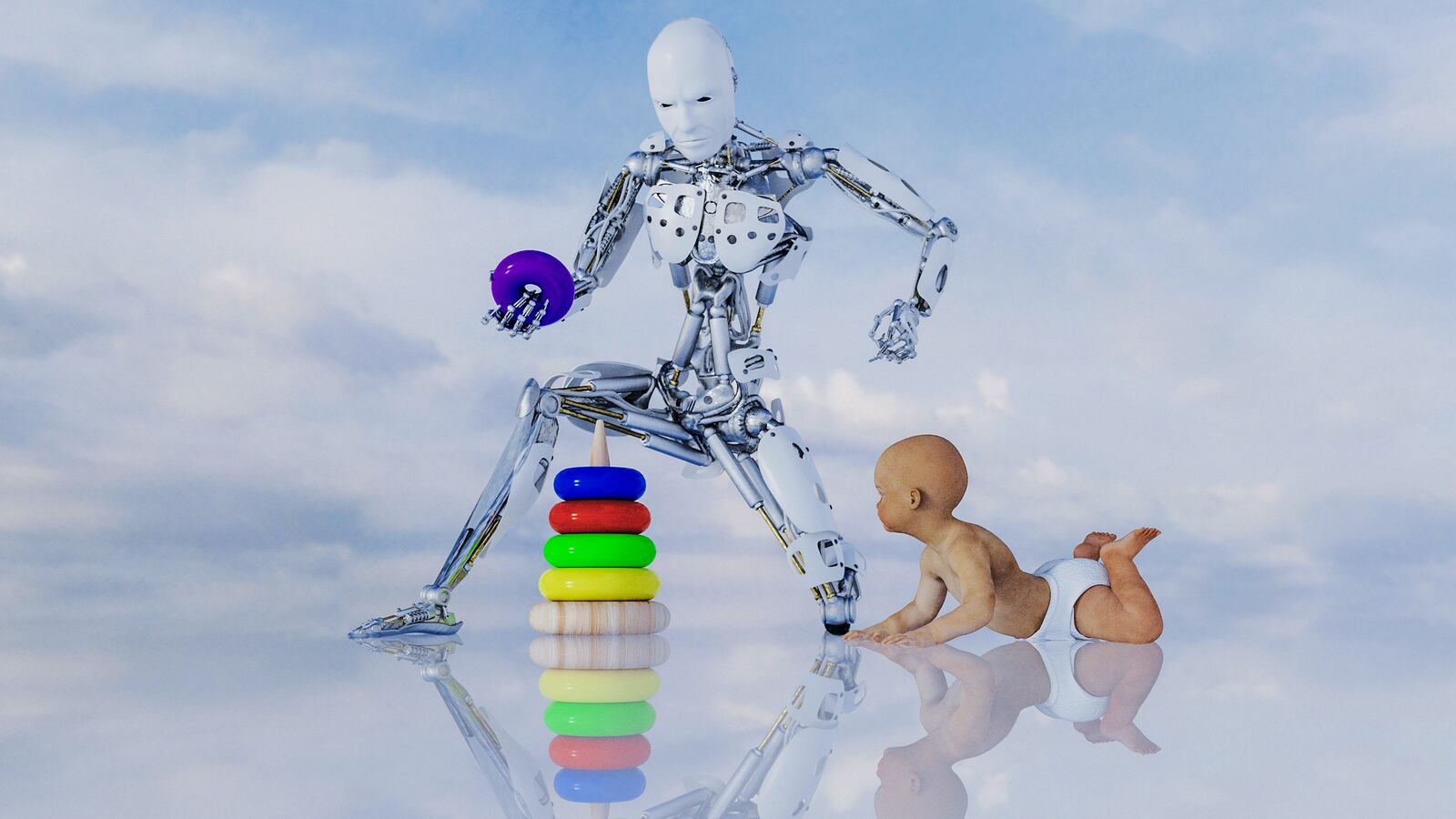

Instead, researchers at Google’s DeepMind built a model using artificial intelligence to approach the debate from a more feasible angle. Published on Monday in the journal Nature Human Behavior, their work pulled from research of how infants understand the physics of objects to train an AI model they named PLATO.

The idea that infants understand physics by breaking up the world around them into discrete sets of objects was a commonality across the body of research, Deep Mind researcher and lead study author Luis Piloto said during a press briefing.

“Understanding the physical world is a critical skill that most people deploy effortlessly; however, this still poses a challenge to artificial intelligence,” Piloto said.

Hespos, who was not involved in the research, posed the team’s central question provocatively in an accompanying essay also published by the journal on Monday: “Can a computer think like a baby?”

Piloto’s team trained their AI model on a collection of three-dimensional animations of rolling balls and moving blocks, with the instruction to separate out objects and track them over time.

Then, the researchers devised a test to compare PLATO with two other AI models that were not built to recognize objects this way. They showed the three models stills from the 3D animations and had them predict what happened next.

The other models didn’t pass all of the researchers’ tests, but PLATO scored accurately across their metrics after just 28 hours of visual experience. This suggests that parsing objects is, in fact, a critical part of physical understanding, Piloto said. The results also confirmed that the researchers accomplished what they set out to do: Make an AI think like a human, or at least a human toddler.

PLATO wasn’t perfect, and made inaccurate predictions more than 20 percent of the time. Hespos said that this discrepancy suggests that infants’ intuitive sense of physics goes beyond just object recognition. But she also said a more accurate model would still be unrealistic.

“I can say, ‘Two solid objects don’t pass through one another.’ Does that mean the baby gets it right every time? No,” she said. “Babies, too, are quite variable.”

Piloto said that the model was “limited” in the sets of shapes, textures, and perspectives on which it was trained and tested. Still, the potential for artificial intelligence to learn from infants’ perception of the world is immense.

“I think physical understanding is pervasive,” Piloto said. “The point of this work is to establish a benchmark so that people know how well their models understand the physical world.”

In the future, models like PLATO may be able to address fundamental nature versus nurture questions. And it’s interesting to think about even stranger questions that this type of work may try to answer in the future—such as how an AI model trained on videos of outer space would react to Earth physics.

In the meantime, behavioral development research will continue to use human test subjects and illusions. Hespos said that she would like to test infants’ reactions to water being poured on cotton candy, making it “disappear.”

“I really think that would shock some babies,” she said.