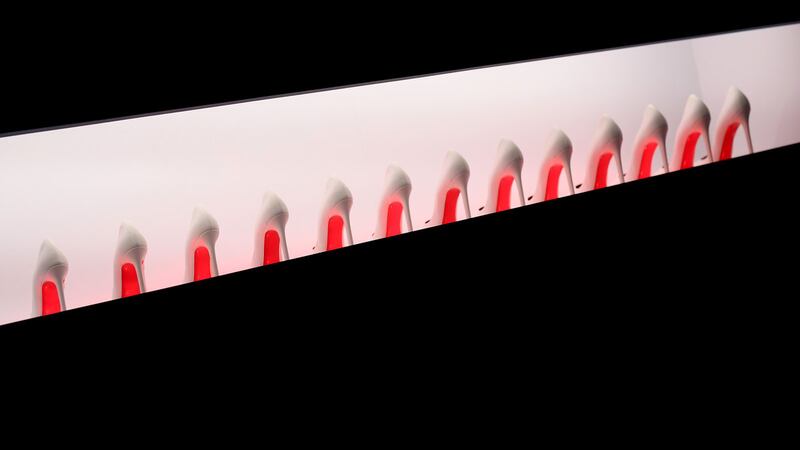

Welcome to a shoe-lover’s dream. As Christian Louboutin, clad in a cheery green suit and seated before the entrance to an exhibition of his work in his native Paris, L’exhibition[Niste], said: “I come from the world of embellishment.”

He’s not embellishing about the embellishment. As anyone who enjoys his shoes knows, including his many celebrity clients, Louboutin does not design for the discreet—right down to his shoes’ “Chinese-red” soles.

L’exhibition[Niste] is displayed until July 26 at the Palais De La Porte Dorée, a monumental Art Deco venue built in 1931. Rather than applying a chronological retrospective approach, it wades into Louboutin’s nearly 30-year career with theatricality and exuberance. Divided into 10 sections, plus an “imaginary museum” of outside influences, the show is immersive and deliciously extra.

ADVERTISEMENT

Louboutin began as an intern at the Folies Bergère amidst showgirls and sequins before he even hit his teens, and he still caters to a flamboyantly glamazon-style form of femininity.

He worked at classical footwear labels like Charles Jourdan and Roger Vivier before he opened his Paris boutique in 1991; his visibility skyrocketed after Princess Caroline of Monaco dropped in. And, of course, celebrities—including Viola Davis, Jennifer Lopez, Jessica Chastain, and Kendall Jenner love him. When Carrie Bradshaw wore Louboutins on Sex and the City, she wore them mismatched.

The show includes a mirrored “Pop Corridor” which is cheekily self-referential, showcasing the way the brand has infiltrated celebrity culture. Images range from Elizabeth Taylor to Idris Elba, Dolly Parton to Timothée Chalamet, interspersed with coverage from TV and print media. There’s Cher crouching on the cover of Vanity Fair.

There’s a New York Times article noting: “it would be hard to keep up with every instance of Mr. Louboutin being lyricized... A partial bibliography would include Kanye West, Drake, Future, Migos, Soulja Boy, Rae Sremmurd, Ty Holla Sign, Iggy Azalea and the complete works of Rick Ross.” (Not to mention Cardi B.’s “Bodak Yellow” in 2017 and Jennifer Lopez’s “Louboutins” in 2009). There’s an Entertainment Weekly headline inquiring: “Did We Really Need to Know that Lindsay Lohan Wore $1,295 Louboutins to Court?” (Answer: of course we did.)

Not all the coverage is overtly flattering. In 2018, Kristen Stewart pointedly removed her Louboutin stilettos mid-red carpet at Cannes and climbed up the Palais des Festivals steps barefoot, to protest the film festival’s heels-only policy. At the Golden Globes in 2014, Emma Thompson removed her peep-toe Louboutins, declaring “I just want you to know: This red? It’s my blood” before flinging the pair over her shoulder and announcing Spike Jonze had won the Golden Globe for Her.

“I propose, and women dispose,” said Louboutin (meaning the French word disposer, as in “to have at one’s disposal”). He did not omit this footage because “People do whatever they want. It would be a bit silly not to accept that your work is seen and perceived differently according to people’s personality. And I totally accept it. I’m not a dictator.”

An early room showcases Louboutin’s earliest works, pre-red sole. (As for how that iconic flourish came to be: Louboutin grabbed red nail polish from an employee to troubleshoot a silhouette he wasn't satisfied with.)

The designs from his early days are low-heeled, and the references are funny rather than va-va-voom. There’s the Maquereau shoe (1987), with a fish tail popping out of the toe and the Toro (1995), a red leather shoe adorned with a black patent leather handlebar mustache.

These, and many others, are surrounded by custom stain-glass pieces, but the Church of Louboutin includes depictions of Josephine Baker in her banana skirt, the Moulin Rouge, champagne flutes, peacocks, billowing headdresses, and other such holy totems.

The early days give way to the “Treasure Room”—anchored by an ornate crafted palanquin—featuring the designer’s more recent creations. These feel worlds away from his debut designs: the person wearing his 2016 Cybersandale (a flashy, strappy, heavily-studded silver sandal) would probably kick a person wearing the 1994 Guinness (“Brewed in Dublin” beer can-branded chunky pumps) in the shins for fun.

Some of Louboutin’s recent work retains the playfulness of his past, rather than accentuating eroticized femininity: like a roll of camera film twisted into a sculptural decorative flourish, or a heel cloaked in a curtain tassel. Some designs are overtly referential—to architect Oscar Niemeyer, Olympian Usain Bolt, or designer Yves Saint Laurent (Louboutin’s YSL tribute shoe walked the final haute couture show in 2002).

Further along, a section is dedicated to Louboutin’s Nudes line, which he conceived as a seamless extension of the leg. A color wheel of flesh tones are executed in assorted designs.

While the range now includes varied hues, when the line was launched, “flesh-colored” was synonymous with “white.” Louboutin told the Independent that a black buyer had told him that “nude” was not nude for everyone: “This is beige. Nude is a color of skin and this is not the color of my skin.” Louboutin widened the spectrum thereafter to five shades; he has since expanded to nine colors.

He has diversified in other areas, too. The first trainer he created, for his male clientele, found quick crossover with women in his studio, who requested versions in their sizes. He’s made larger sizes of his heels to satisfy requests from men.

The show concludes with a “Fetish” sequence: a darkened passageway spotlighting a 2007 collaboration between Louboutin and David Lynch. The shoes featured are purposefully dysfunctional: Siamese heels fused together; basically verticalized pointe shoes. Lynch photographs anonymous women in these fetishized shoes in his typically macabre, uneasy atmosphere.

Although the Lynch-Louboutin pairing is purposefully exaggerated, it underpins that, even for many “functional” designs, a woman’s sex appeal is prioritized over her sense of ease and equilibrium. Being poised and seductive is more pressing than the expectation she feel comfortable and mobile. Many women find heels empowering, but it’s a physical compromise for a conceptual boon.

Louboutin’s shoes weaponize sexuality, although he is hardly the only designer who does it, and if anything, the exceptional humor, creativity, and craftsmanship he brings to his métier compensates to some degree. The exhibition stylishly and vivaciously celebrates the designer’s legacy—but hopefully it prompts viewers to rethink what empowerment south of one’s ankles should, in fact, look like.