Scrutinizing images from a large telescope in Spain, a team of mostly European astronomers have found what seems to be a very rare kind of exoplanet 31 light-years from Earth.

The seemingly wet, airy planet called Wolf 1069 b “could very well possess the key factors in making it indeed a habitable world,” a team led by Diana Kossakowski, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany, wrote in a peer-reviewed study, the latest version of which appeared online on Feb. 2. The study is slated to be published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

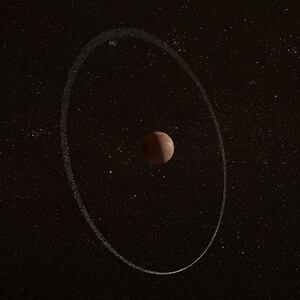

Wolf 1069 b could be Earth’s cousin. But if so, it’s that weird third cousin you avoid at the family reunion. Yes, it seems to be the right size, temperature, and composition to make a pretty good home for life as we know it. But Wolf 1069 b apparently spins at just the right speed to keep the same side facing its star at all times. That means there’s constant light or constant dark depending on which half of the planet you’re on. Equally weirdly, Wolf 1069 b might be all alone in its star system. No neighboring planets. Not even a moon to keep it company.

With its mix of familiarity and utter alienness, Wolf 1069 is unique among exoplanets. Imagine Earth, but take away its day-night cycle, delete its moon and erase all the nearby planets in its night sky.

The uncanny exoplanet could help us redefine what we consider a livable planet. “Wolf 1069 b is a noteworthy discovery that will allow further exploration into the habitability of Earth-mass planets,” Kossakowski’s team wrote.

Color Out of Space

Kossakowski and her coauthors discovered Wolf 1069 b in data gathered by the Carmenes instrument on the 11.5-foot telescope at the Calar Alto Observatory in Spain. Carmenes—which became operational in 2016—detects the color shifts of a very faraway object in space.

Those shifts, the results of accordion-like changes in the wavelengths of light reflecting from the object, can indicate that object’s movement relative to the observer. An object that changes color in certain ways, in certain spans of time, might be a planet.

Analyzing images that Carmenes captured between 2017 and 2020, Kossakowski’s team—including scientists in Cyprus, Germany, Spain and the U.S.—noticed something odd. Spectral patterns indicating a solitary planet orbiting the dwarf star Wolf 1069.

The planet appears to be roughly the same size as Earth and similar in composition. That is, rocky rather than gassy. Equally importantly, Wolf 1069 b orbits its low-mass star at a distance of around 650,000 miles, placing it in the “habitable zone” of the star. Just close enough to maintain a cozy temperature—and, therefore, potential life.

Wolf 1069 as seen by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

Wikimedia CommonsScientists have identified more than 5,000 exoplanets. Not many of them are Earth-sized and in the habitable zone of their stars. In fact, there are just 20 confirmed exoplanets that meet these criteria. Of them, Wolf 1069 b is the sixth closest to Earth.

All things being equal, Wolf 1069 b should be one of the top priorities as scientists both search the cosmos for signs of alien life and build a roster of habitable planets that our descendants might eventually colonize. But Wolf 1069 b has a few weird features. It seems the planet spins around its own axis at the same rate that the planet itself orbits around its star. In other words, the same half of the planet is always facing the sun. There's a permanent night on the far side, and a permanent day on the near side.

That doesn’t mean Wolf 1069 b can’t support life. It does mean it’s probably only half-inhabitable—and only by species that can adapt to around-the-clock light or dark.

Giant Impact

There’s also the fact that there’s no clear evidence of other planets orbiting the Wolf 1069 star. That’s really rare. So rare that Kossakowski’s team speculated there once was at least one other planet in the system—but, a long time ago, they collided with Wolf 1069 b. “Perhaps Wolf 1069 b had a violent formation history,” the scientists wrote.

That kind of planetary collision—a so-called “giant impact”—is actually pretty common in the early eons of a star system’s formation. A possible giant collision between Earth and a long-gone neighboring planet 4.5 billion years ago may have reshaped our then-young planet.

Massive collisions are unimaginably destructive. But they can also be enormously productive once the proverbial dust settles, millions of years after impact.

That’s especially true with Earth. “I think that impacts created a great diversity of environments on Earth, possibly including the continents themselves, that ultimately enabled complex macroscopic organisms to evolve,” Tim Johnson, a geologist at Curtin University in Australia who wasn’t involved with the study, told The Daily Beast.

A collision on that scale can also eject massive amounts of debris into the larger planet’s orbit. Debris that, over time, can clump together and form a moon. That’s apparently how our own moon formed.

Another thing that’s strange about Wolf 1069 b is that the planet seems to have benefited from all the geological mixing resulting from an apparent giant collision, but doesn’t have a moon that we can see with our existing telescopes. Maybe the moon is there but we haven’t found it yet. Or maybe a moon never formed and, having absorbed all its planetary neighbors, the exoplanet really is alone in its corner of the galaxy.

The absence of a moon has some fascinating implications. Our own moon tugs on our oceans with its gravity, thus creating our tides. Billions of years ago, tides repeatedly stranded simple aquatic organisms on dry land, forcing them to adapt. “Tidal displacement of the surface water … seems to have helped life on Earth to emerge from the oceans,” Thomas Fauchez, a space scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland and a member of Kossakowski’s team, told The Daily Beast.

To be clear, evolution is theoretically possible without tides. “It is not necessary that a large moon needs to be present for a planet to have life,” Rajdeep Dasgupta, a planetary scientist at Rice University who was uninvolved with the study, told The Daily Beast.

But these tides “would definitely impact the planet's subsequent evolution,” Dasgupta said. They’re an astrobiological bonus. So if there’s already life on Wolf 1069 b, it probably followed a very different evolutionary path than Earth life did.

Surveying the Future

It’s possible Kossakowski’s team is wrong, of course. Everything we currently know about Wolf 1069 b, we gleaned from a few colorful but blurry images. As our telescopes improve, our data should improve, too. Maybe we’ll discover we were wrong about the half-dark but apparently habitable planet.

Fauchez is especially keen to confirm whether Wolf 1069 b really is all by itself. “Future surveys of Wolf 1069 b could search for an inner planet within the system,” he said, pointing out that the exoplanet Proxima Centauri b seemed to be all alone until a follow-up survey spotted a nearby planet.

On the other hand, these same future surveys could discover even more weird planetary attributes. Kossakowski and her colleagues stressed that a planet with no moon and no tides “can lead to unique atmospheric circulation pathways” that, at present, we can only really guess at.

On Earth, for example, it tends to rain more when the moon is high in the sky, its gravity slightly warping our atmosphere. On Wolf 1069 b, there might not be a moon to weigh on weather patterns.

Right now, Wolf 1069 b appears to be really odd but perfectly liveable for us or some alien species. Further study could make it seem more liveable, or less. Maybe it’s less like Earth’s strange third cousin and more like a sister. Or maybe it doesn’t belong in the family at all.

Either way, we should know more soon. Fauchez said he and his colleagues are already putting together a plan for further investigation of the uncanny exoplanet.