They can fly, they can crawl, they can skateboard—and now they know how to jump hundreds of feet into the air. Researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara have built a robot that can vault up to a record-breaking 100 feet in the air, according to a new study published Wednesday in the journal Nature. The robot, which looks like a bunch of bicycle wheels mashed together, uses some unique engineering to overcome the mechanical limitations holding us back from jumping very high. Its inventors suggest the new bot may help us with exploring dangerous environments here on Earth and potentially other planets out in the void of space.

The robotic jumper is constructed with springs, rubber bands, and a rotary motor.

Elliot HawkesIn order to jump really high, the laws of physics dictate you need to do two things: accelerate really fast, and apply a massive enough force with your leg muscles to propel you upwards. Of course, you could optimize your jumping approach as many athletes who train for the high jump or pole vault train do. But there are still limits to how much force and energy you can generate in a single moment.

But with some good engineering, robots can soar to heights we humans can only dream of. The robot created by the UCSB team stands only at about 30 centimeters tall, just shy of a bowling pin, and weighs about as much as an average adult mouse at 30 grams. Despite its diminutive size, it can jump more than 100 times its own height thanks to springs and rubber bands that store energy, and a rotary motor that multiplies the amount of force and energy produced for a single jump.

This is a first in the field of robotic jumpers. Previous notable contenders have been Boston Dynamics’ Sand Flea back in 2012, which could jump up to 32 feet; and SALTO, a jumping robot created by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, in 2018 that could jump five times in four seconds for a combined height of nearly 28 feet. The UCSB team hopes their research will foster a better understanding of how jumping could be a viable means of locomotion for robots. They see a potential for jumping robotic explorers here on Earth that could be used to collect images below ground in places like caverns. It could also be used in space exploration missions on places like the moon where gravity is weaker and could allow “robonauts” to jump even higher—up to 410 feet—and leap long distances in a single bound.

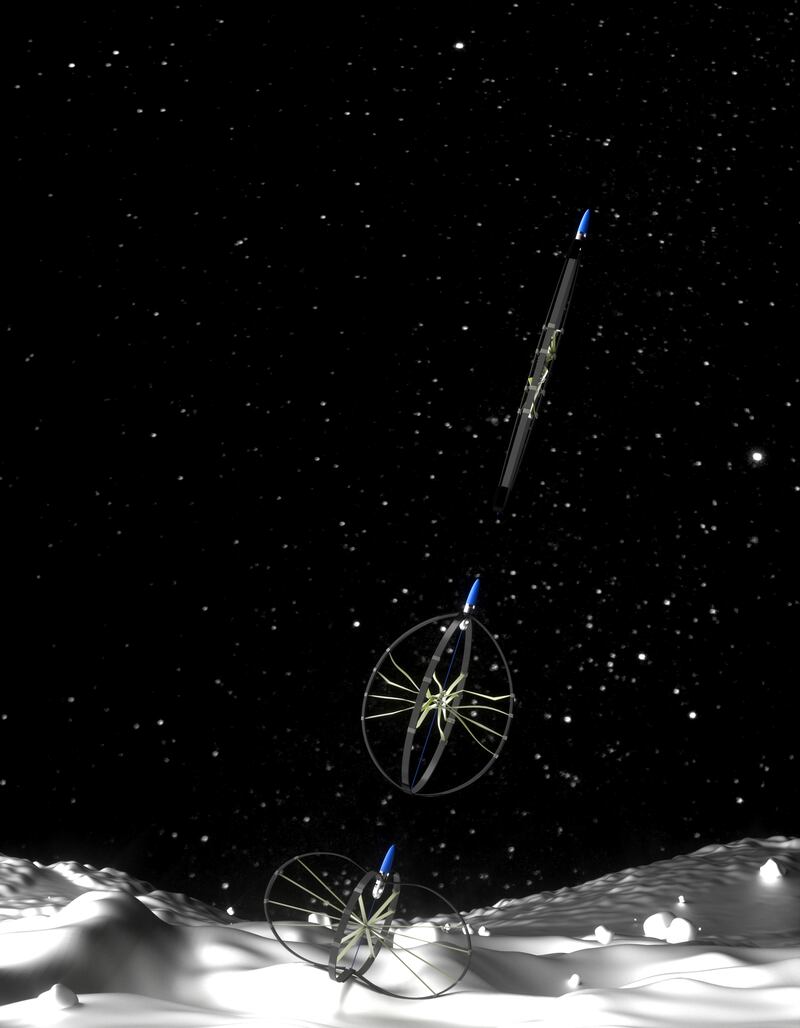

Artistic rendering of the robotic jumper on the moon's surface.

Elliot Hawkes