Like many aristocratic couples of their generation, my paternal grandfather, the writer Christopher Sykes, and his wife, Camilla, née Russell, had separate bedrooms.

Camilla was a famous beauty in her youth and when I knew her, in her 70s, she still proudly asserted her right to look fabulous. Her room at their substantial house in a small Dorset village—where they had moved in 1952, having no further use for the city after the king died—was an Aladdin’s cave of jewelry, powders, perfume, pills, shoes, and foreign clothing piled high on elegant mother of pearl-inlaid tables and overflowing from lacquered chests of drawers.

She entertained visitors, including her husband, on an upholstered love seat, a sofa that resembled two armchairs joined together but facing each other, thereby forcing you to stare straight into her eyes when sitting on it.

Christopher, a writer who was famous for his love of what in 1980s England was still considered to be an eccentric French pastry, a mysterious thing called a croissant—vast quantities of which were bought at a specialist baker in London and frozen; not for nothing did we call him Fat Grandpa—had a separate bedroom lined with his beloved history books.

He would sometimes emerge from here in the evenings wearing a glamorous silk dressing gown. His own room was tidy and very, very male. He couldn’t have borne to be surrounded by Camilla’s fripperies. They both had separate dressing rooms as well.

The separate bedrooms were a simple acknowledgement of the fact that, although married, they liked their own space too.

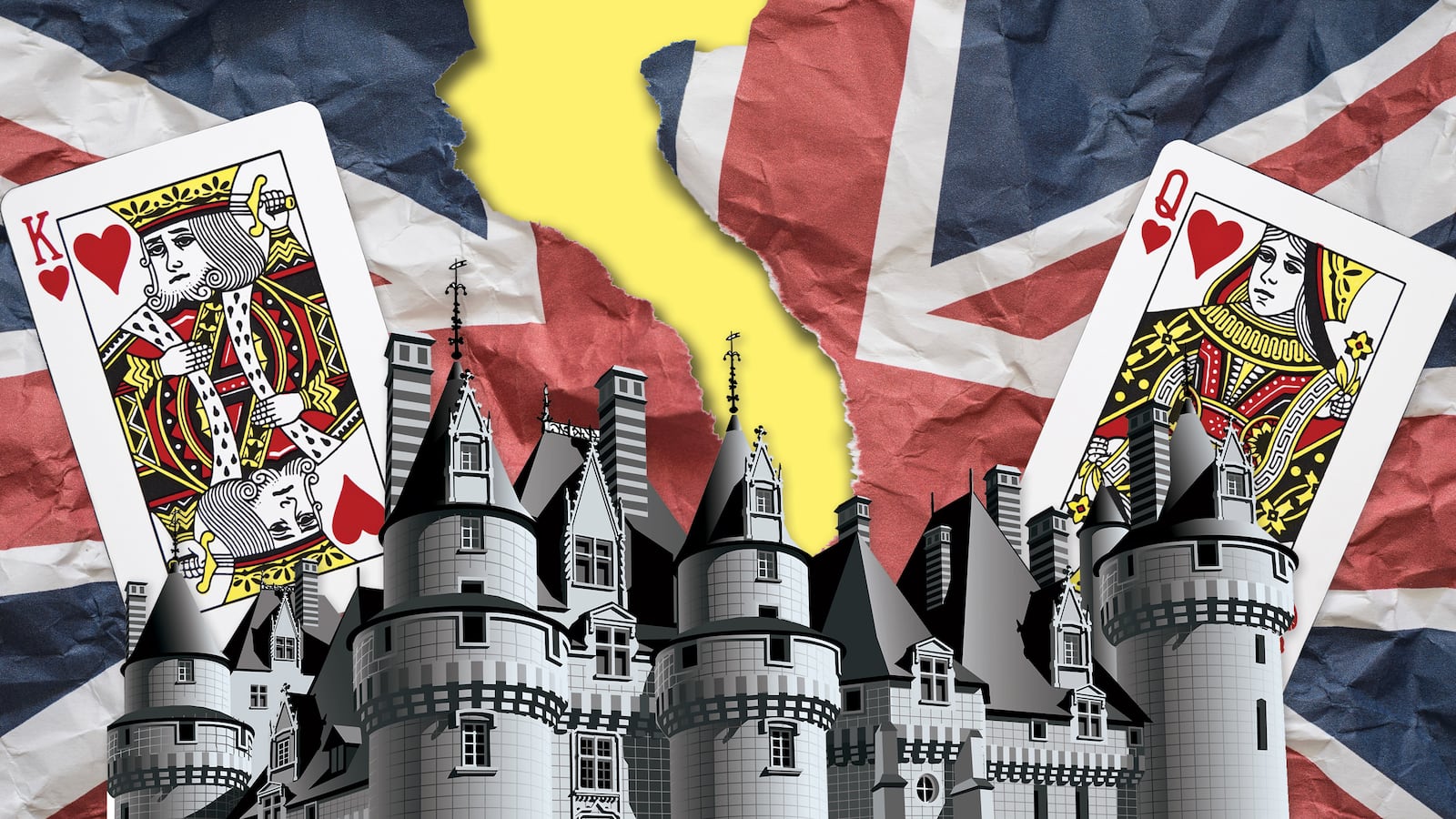

However, I think even they would have drawn the line at the living arrangements of the Duke and Duchess of Norfolk, who have spent the past five years of their life living in separate wings of the 11th-century Arundel Castle after their relationship hit a rough patch. Georgina stayed in the more homey west wing, long the family home, while Edward decamped several hundred yards to the more Spartan east wing, which had been used to house staff in days gone by.

Happily, the duke has now moved back into the west wing, rejoining his wife—the queen, a close friend, is said by the Mail on Sunday to be “delighted” at the rapprochement—although after all those years of enjoying their own space, it would be a fair bet that they are still sleeping in separate bedrooms.

For the Norfolks, their dispersal around Arundel Castle was a way to live separate lives while avoiding the trauma of divorce, which they refused to consider for both practical and religious reasons. The Norfolks are among the most senior lay Catholics in the otherwise largely Protestant United Kingdom.

They nobly refused an invitation to the royal wedding of William and Kate, as they did not wish to hypocritically sit next to each other.

However, the banishment of one’s partner (or their own voluntary exile) to a dower house or distant section of the building is by no means a foible unique to the Northumberlands. It is a well-documented part of upper class British life.

A similar situation developed in the case of an Irish aristocrat I know. In this case the wife remained in the big house while the husband, who suffered from severe depression, moved into the gate lodge at the bottom of the drive.

“What are we supposed to do?” the châtelaine told me when explaining the developments a few years ago. “There’s no sense getting divorced, or there will be nothing left for the kids.”

She started an affair with a musician quite openly and encouraged her husband to do something similar. He did not, and has since died. Out of the tragedy, a glimmer of salvation is that the estate has been successfully preserved for her children.

The sheer size of most stately homes allows for troubled marriages to be given time and space to heal—or not heal—without outsiders being any the wiser.

And the tradition of separate bedrooms for the master and mistress of the house provides a useful cover behind which to hide marital breakdown. While not as completely standard as some reports suggest, separate rooms were certainly very common before World War II in any sizable house, even when the relationship was untroubled.

Marie Stopes, writing in 1918, advised provision of a single bed “in a nearby dressing room for when either of the partners desires solitude.”

The custom has even made its way into fiction: In Downton Abbey, occasional references are made to the fact that Lord Grantham has his own room, even though he usually sleeps in Cora’s bed.

The queen and Prince Philip observed the habit of sleeping in separate rooms—a fact that was only made public after an intruder broke into the queen’s bedroom in the most shocking security lapse at Buckingham Palace on record.

The break-in was said to have been facilitated by the fact that the queen insists on sleeping with the windows open—Philip prefers the windows closed, hence his desire for his own room.

Prince Charles and Camilla have separate bedrooms at Highgrove, Charles’s house, but Camilla goes one step further and has kept her own family house, which predates her marriage to Charles and to which Charles is not, as a rule, invited. It’s very much “her place,” say sources.

There is evidence that, as many of the middle classes now occupy houses of comparable size to small manor houses, they are starting to emulate this aristocratic habit. According to one survey, some 9 percent of married (or partnered) British couples now sleep in separate rooms. In Japan, the figure is 28 percent.

My grandparents would certainly have approved.