A leading psychiatrist has called for the reclassification of magic mushrooms, LSD, and other psychedelic drugs on the grounds they could be crucial in treating mental health problems.

James Rucker, honorary lecturer at King’s College London’s Institute of Psychiatry, proposed that legal restrictions on the use of such substances be lifted and used to aid ailments such as anxiety and addiction.

Such drugs “were extensively used and researched in clinical psychiatry” during the ’50s and ’60s, Rucker wrote in the British Medical Journal, but were prohibited in 1967 following fears that they were causing psychological harm—in spite of medical evidence to the contrary. But more than two decades after they were classified as Schedule 1, materials in accordance with the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances, the U.S.’s war on drugs was revealed to be little more than fear mongering.

In 1992, John Ehrlichman, former assistant to Richard Nixon, admitted that the administration had stoked misgivings about the harmful effects of drugs and exploited the public’s lack of awareness for their own political gain—a move which means, 50 years later, psychedelics face more restrictions than heroin and cocaine.

“Hundreds of papers, involving tens of thousands of patients, presented evidence for their use as psychotherapeutic catalysts of mentally beneficial change in many psychiatric disorders, problems of personality development, recidivistic behaviour, and existential anxiety,” Rucker says of the drugs’ medical history. “No evidence shows that psychedelic drugs are habit forming; little evidence shows that they are harmful in controlled settings; and much historical evidence has shown that they could have use in common psychiatric disorders.”

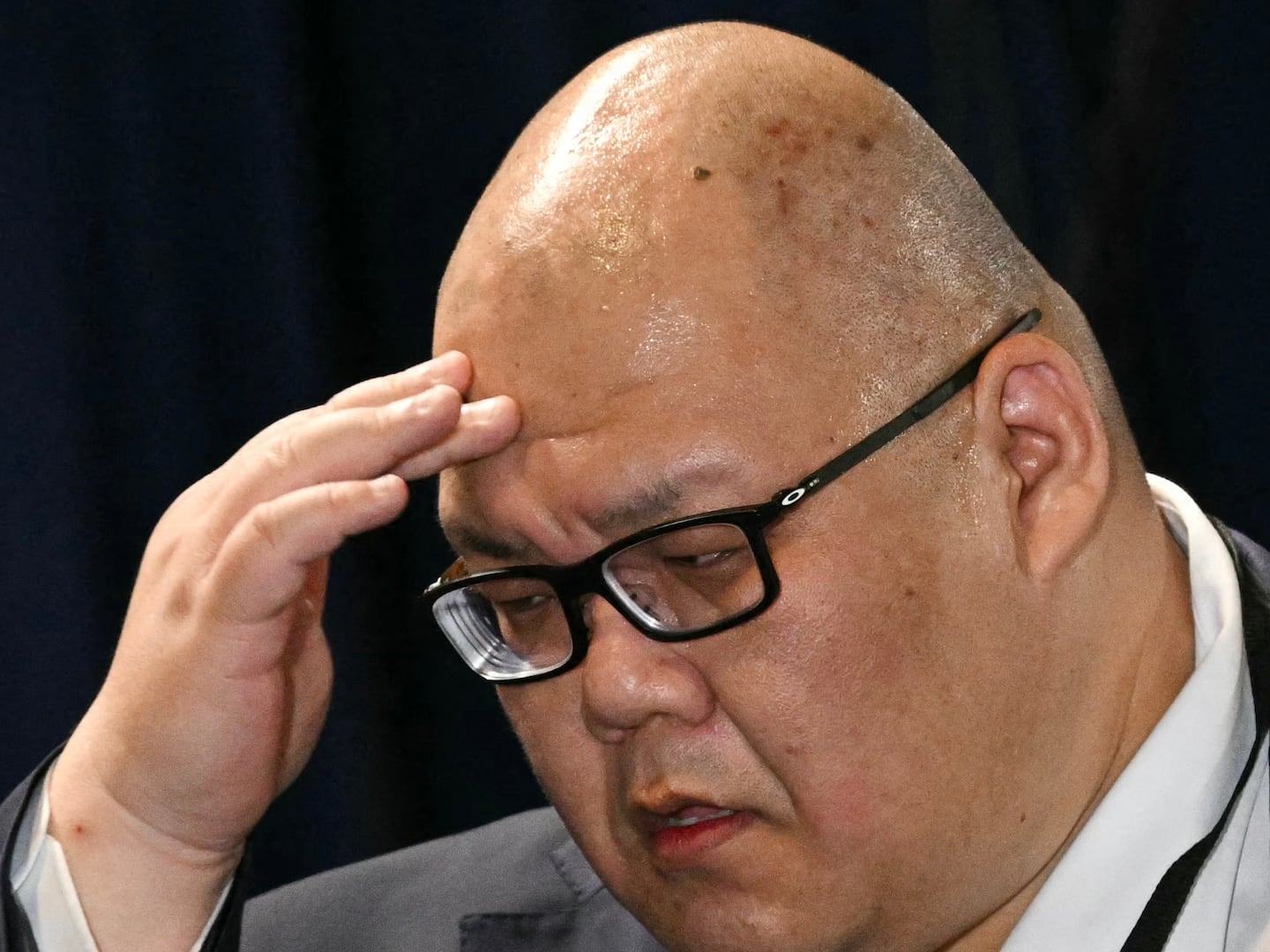

Christopher Evans, director of UCLA’s Brain Research Institute, agrees with Rucker’s examination: “Many of these highly restricted hallucinogenic drugs should be considered for their therapeutic potential in well-controlled clinical studies in controlled environments. Though I believe the drugs should remain closely regulated (like opiates), the restriction should be geared to allow clinical research.”

Organizations around the world—most recently in Norway—have begun contesting the current restrictions. There have also been a number of pilot studies undertaken to test the clinical efficacy of psychedelic substances when used as treatment for ailments such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcohol addiction, and cluster headaches, the results of which support Rucker’s claims. A study published last week in the Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry journal has even suggested psychoactives such as MDMA may help treat PTSD.

One of the principal qualms surrounding the use of psychedelics is that they will induce dependence, but existing research shows that this is not the case. LSD was named the safest psychotropic—a substance that alters brain function and perception—in a 2010 analysis of potential harms caused by drugs of this nature, and is significantly less likely to result in a toxic dose than alcohol, cocaine, or heroin.

“Drug legislation has been bias toward groups of people that are associated with the drug and of course financial interests as opposed to the intrinsic harm the drugs cause to the population and addiction liability,” Evans says. “Hallucinogens certainly have potential therapeutic value in many diseases and are much less likely to become problematic to society than psychostimulant therapeutics such as methylphenidate and amphetamine, and opiate therapeutics such as Oxycodone or Vicodin.

“Addiction is not the problem.”

It is not only that its effects have been misrepresented, then, but that its benefits have been suppressed in favor of antediluvian political propaganda. A U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health from 2001-2004 found that those who reported use of psychedelics had lower levels of serious psychological distress, with no need for mental health treatment. No association with psychosis was uncovered.

The classification means that pilot studies on the effects of the drugs remain challenging. Rucker cites the “practical, financial and bureaucratic” barriers to carrying out trials with psilocybin—the naturally occurring compound in magic mushrooms—as a result of the UN’s mandate. Only one manufacturer in the world holds enough of the correct quality to be used effectively, and costs some $153,000 for 50 doses. In the UK, holding the drug requires a $750,000 license (which only four hospitals have) and regular inspections from police. As such, the price of clinical trials for psychedelic substances is up to 10 times higher than those for heroin.

In view of the evidence, then, perhaps it’s time we stop dismissing shrooms and hallucinogens as the pastime of underachieving college kids and re-examine their potential impact on the medical world.