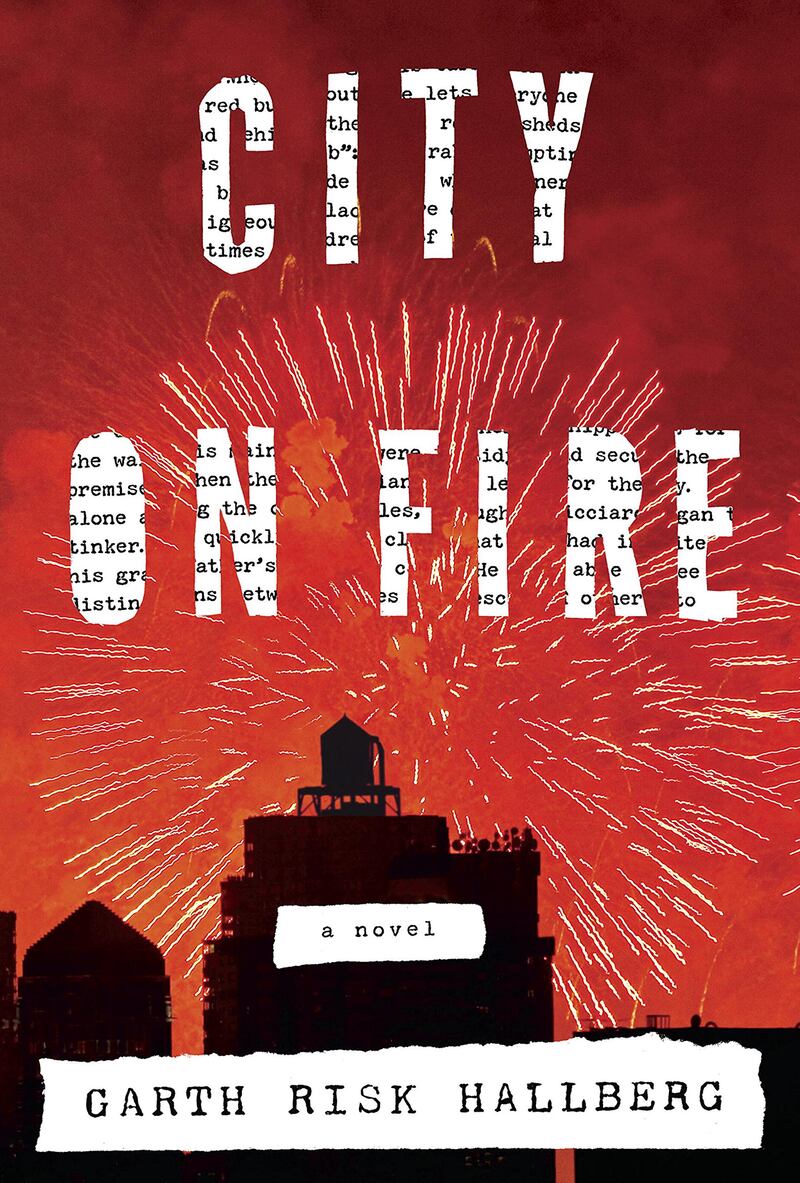

City on Fire, the debut novel from Garth Risk Hallberg, is as massive (944 stuffed-to-bursting pages) as the advance that Hallberg reportedly received for it (nearly $2 million, which would be probably unfair to mention in the first sentence of a review if it wasn’t already such a large part of the book’s pre-publication buzz), so lets save some space here at the top by immediately attempting to map the simultaneously expansive and involute plot.

Set in the Bad Old Days of New York City in 1976-77, the story includes two formal units whose ranks include most of the main characters. The first is the monied and landed Hamilton-Sweeney family of the Upper West Side, the two scions of which have long been estranged. William, who has thrown off the mantel of wealth for his preference of art and heroin, can be found living with his boyfriend Mercer in a tiny Hell’s Kitchen apartment. William’s sister, Regan, is still involved in the family business of turning money into more money, but her role in communications might not be senior enough to stop the usurpation of the family power by one Amory Gould, the ice-cold “Demon Brother” whose sister married into the Hamilton-Sweeneys via the space vacated by William and Regan’s deceased mother. Regan has two kids with a man named Keith—remember him for later.

Way down and across town is the East 3rd Street stronghold/flophouse of a band of musically un-gifted punks calling themselves the Post-Humanists. It’s the messianic lure of the group’s leader (a man named Nicky Chaos, who is frequently in receipt of mysterious envelopes sent by the Demon Brother) that draws suburban teens Charlie and Samantha onto the LIRR into the city to join in on the Post-Humanist activities, which include but are not limited to drugs, arson, and of late, bomb-making.

Charlie loves Samantha. But Samantha is having an affair with Keith, Regan’s husband who I mentioned before. Then Samantha is shot mysteriously on New Year’s Eve and falls into a coma, and the other characters swirl around her for seven months, bumping into each other and brooding over their back-stories, until all lines attempt to converge during the great blackout of 1977. There’s also a world-weary detective, and a world-weary reporter, both trying to figure this whole thing out. Oh, and the reporter’s neighbor also gets involved.

Yeah, it’s a lot. In light of the book’s page count, I am required by law to describe it, back-handedly or not, as ambitious, but it also displays and nearly achieves the genuine ambition of these type of big books—that is, to use the structure or frame of the narrative to describe a kind of logic that in turn defines or reflects the narrative’s content. Namely, in this case, that the organized chaos and excess and everything-at-onceness of the plot, which doesn’t arc so much as circle around itself in tighter and tighter orbit, will create in the mind of the reader a grand edifice something like New York City itself. In fact, Mercer, a frustrated novelist, fantasizes about writing such a book: “In his head, the book kept growing and growing in length and complexity, almost as if it had taken on the burden of supplanting real life, rather than evoking it. But how was it possible for a book to be as big as life?”

Hallberg has tried mightily and he nearly pulls it off. Judged strictly as a product of effort and determination, the book is an absolute marvel. A Russian nesting-doll analogy would not quite serve, as there are so many separate dolls all with their own nests, and all intersecting at various orders of magnitude. Perhaps fractalized nesting dolls? A nesting doll in the fourth dimension? And then there are the interludes, among them: found letters, emails, a medical information sheet, and an issue of Samantha’s punk zine, rendered with high fidelity.

It could and probably should be said that the book is work of genius, in the sense that doing something extremely impressive is usually extremely hard, but that doesn’t necessarily make for fully rewarding reading. Humor is in short supply. The characters’ voices all blend together into the same over-educated monotony. Descriptions, told in vocab-quiz bonus words, are accurate and interesting, but stop well short of beauty. And it’s hard to remember, as the weight of the book strains your arms, just who you’re supposed to care about enough to lug this thing around.

The skyline of New York City has changed quite a bit in the last 40 years, as developers have thrown up dozens of new glass-walled luxury skyscrapers that sit largely vacant most of the year, their farcically-priced units serving a tax shelters for Chinese and Russian oligarchs. Here, perhaps, is our analogy: monumental and perfectly engineered, but little humanity to be found.