By September 2020, police officer Robert Black was at his wit’s end.

Over his year of service in the department of Millersville, Tennessee, Black had allegedly been subjected to sexual harassment, including from a female officer who used a racist slur while grabbing his genitals. The police chief, whom Black suspected of harboring Ku Klux Klan ties, had allegedly made disparaging comments about Black’s biracial son. The assistant police chief was under investigation for allegedly assaulting his wife during a dispute over an alleged affair with a drug suspect. Through it all, management allegedly silenced officers’ complaints by instructing them to support the “thin blue line.”

“Nobody would listen to what was going on up there,” Black told The Daily Beast. “Nobody cared.”

So Black made a fake Facebook profile, reached out to Black Lives Matter organizers, and blew the whistle on his department. Days later, he was fired. At least two other officers who allegedly clashed with management departed soon thereafter.

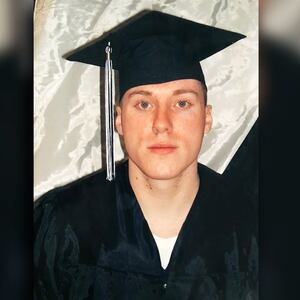

In a new lawsuit, first reported by Nashville’s NewsChannel 5, Black and former Millersville Police sergeant Joshua Barnes describe a culture of harassment and intimidation in their former department. Both men cite a pattern of alleged racist behavior from the department’s leadership—directed at Barnes because he is Black, and at Black because he is white with a biracial son.

The lawsuit’s three defendants are Millersville Police chief Mark Palmer, assistant chief Dustin Carr, and the city of Millersville. Carr did not return The Daily Beast’s request for comment. Palmer stated that, although he would like to address the suit’s allegations, all comments must be directed through the city and its manager. Millersville’s city manager did not return requests for comment.

The case is not the first time Palmer and the city have faced a lawsuit from within their ranks. In 2015, two men who had previously been Millersville’s only Black officers sued Palmer and the city, alleging racial discrimination.

In their lawsuit, which was dismissed with prejudice in 2016, both men claimed Palmer had told each of them that “I don’t like n-----s.” One of the former officers, Anthony Hayes, claimed Palmer took him on an unexplained visit to a former KKK leader’s home, where Hayes “was subjected to an extended conversation in the presence of KKK memorabilia.” Hayes also accused Palmer of placing a copy of a KKK magazine in Hayes’ locker, with a sticky note that read “this was left for you—don’t let your subscription run out.” In their response to the lawsuit, the city denied the allegations against Palmer. (The plaintiffs included in their lawsuit an email from the city manager stating that Palmer would be disciplined in the magazine incident.)

Hayes and the other former officer, Brian McCartherenes, claimed to have been forced out of their posts after they accused the department of racism. Hayes claimed he was “forced to resign” following a punitive shift change. A police memo shows that McCartherenes was fired for alleged racist conduct, because he told a new Black officer that “at the end of the day, remember you are Black.”

McCatherenes claimed he intended the statement as a warning about the risks of being a Black officer in a small town. That new officer was Joshua Barnes, one of the plaintiffs in the latest suit against Millersville’s police brass.

Barnes claims he soon encountered a culture of racism firsthand. Palmer called Black people “n-----s,” “monkeys,” and “animals,” Barnes alleges in his suit, adding that Palmer invoked racial stereotypes about Barnes “always want[ing] to get some fried chicken and watermelon.”

Barnes claims the legacy of Millersville’s previous Black officers lingered over his own employment. Assistant police chief Dustin Carr “informed Sgt. Barnes that Millersville did not want to hire Black people because they may sue the City ‘like Anthony [Hayes] and Brian [McCartherenes] did,’” the lawsuit alleges. Barnes claims the department hired only one other Black person during his tenure: an officer whom Palmer allegedly joked was related to O.J. Simpson. The officer lasted “a few months before he left out of frustration due to Mark Palmer’s racist comments,” the suit reads.

When Robert Black joined the force in June 2019, he had been unaware of its reputation. That changed quickly, he claims, when Palmer learned that Black’s son is biracial. The lawsuit claims Palmer expressed dissatisfaction with Black, telling another officer that “Robert is a little different. He’s not one of us.” When the other officer asked what Palmer meant, the chief allegedly replied “well you know, his kid and all… He’s just not one of us.”

Black told The Daily Beast that Palmer started treating him with hostility around the time of the alleged comments. Other Millersville officers also allegedly turned against Black. A female officer allegedly made repeated unwanted advances toward Black. At one point, according to the lawsuit, the officer allegedly grabbed Black’s genitals through his pants. When Black told the colleague to leave him alone, she allegedly responded “why? Because I’m not a n----r?”

Although Black claims to have reported his colleague, his supervisors allegedly refused to pursue the matter, with Carr allegedly making his own sexualized comments about Black. (Black told The Daily Beast that Carr gave the nickname “Tripod” in the office. “It made me feel very weird,” Black said, adding that other officers picked up on the name before he learned it was an innuendo.)

Carr, meanwhile, was facing other accusations of impropriety after he allegedly began a relationship with a Millersville woman who was charged, but never convicted, on multiple drug counts. Carr was married at the time. In April 2020, according to Barnes and Black’s lawsuit, Carr allegedly assaulted his wife when she accused him of infidelity. Carr began bringing his new partner into the office in May “much to the chagrin” of some officers, the lawsuit alleges.

That month marked another flashpoint for law enforcement. The murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer set off nationwide protests, allegedly enraging Palmer. In the lawsuit, Barnes claims to have witnessed Palmer watching a video of a protest in Nashville, during which Palmer allegedly called the demonstrators “n-----s” and “animals.” “Let these motherfuckers come to my house,” the lawsuit claims Palmer said. “I’ll shoot ’em and string those fuckers up in my front yard.”

In August 2020, Nashville’s WSMV reported, the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation began investigating Carr for alleged domestic violence. (A TBI spokesperson told The Daily Beast the investigation into Carr “remains active and ongoing.”)

Barnes and Black allege that Carr and other police leadership became convinced that officers were leaking details to investigators. According to the lawsuit, and an October 2020 report by NewsChannel 5, Millersville Police pressured officers not to cooperate with the TBI investigation. “Chief Palmer berated Barnes about the ‘thin blue line,’ and the need to cover for other officers,” the lawsuit alleges.

But while Palmer allegedly warned officers against speaking to TBI officials, Black was ready to go public with a growing dossier of complaints. Following Palmer’s alleged remarks about Black’s son, Black had read up on Hayes’ and McCartherenes’ 2015 lawsuit, particularly Hayes’ account of finding a KKK magazine in his locker.

“This KKK publication is not something you can go get at the library. You can’t go buy it at the 7/11. These publications are like, homemade, produced on someone’s printing press. It’s hate literature,” Black told The Daily Beast.

The rarity of the publication, plus Palmer’s alleged field trip with Hayes to a former KKK house, led Black to suspect the police chief had current or former Klan ties of his own.

“You can’t find this anywhere,” Black said of the magazine. “That’s why I hit up BLM [Black Lives Matter] reps. I was like, ‘hey y’all…’”

Black said that in September 2020, he made a pseudonymous Facebook page and began seeking out Nashville-area Black Lives Matter activists. “I started letting them know: hey guys, maybe you want to look into the police chief up here. It’s a small city and everyone’s so focused on Nashville. This guy was apparently in a KKK lawsuit by a Black cop five years ago.”

Activists decided to host a mid-September protest against Palmer. Black said he wanted to promote the protest using his pseudonymous Facebook account, but didn’t know how to share the event information. Frustrated, he said he asked a room full of officers, who either appeared to support him or actively helped him share the post.

“My sergeant closed the squad room door,” Black recounted. A detective said “‘here’s how you do it.’ He grabbed my phone from me and started sending out the messages.” (The Daily Beast was unable to reach the detective for comment.)

His success was short-lived. On Sept. 11, 2020, the city fired Black, citing his promotion of the protest.

“These posts have been shared multiple times, and there is no way we can know at this time whether a large crowd will in fact show up at City Hall this coming Thursday evening,” an email from Millersville’s then-manager reads. “As a result of your actions, the City has been forced to incur expenses and devote resources to prepare for a potentially large and unruly mob of angry protesters. Your conduct has put the lives and property of our citizens in danger.” (The protest took place several days later, without any such “mob” or arrests.)

Black’s firing was the first in a wave of departures. In his lawsuit, Black claims the city’s then-manager told him to “tell everyone who is involved in this [BLM protest] that we are coming after them next!”

An officer who witnessed him send the protest invitations resigned the day of Black’s termination, he said. The lawsuit also describes Barnes and another officer as being forced out in the following weeks. Barnes, who claims to have been moved onto another shift in punishment for his ties to Black “could no longer deal with the stress from the Defendants’ constant retaliation, and on October 2, 2020, he resigned from his position,” the lawsuit reads.

Another officer was allegedly instructed to “pick a side” and chose to resign in October. A NewsChannel 5 report that month cited at least four officers as leaving the department over the previous weeks.

Black said he hopes his lawsuit will clear his name so that he can one day return to policing.

“I tried to do my job. I tried to learn, I tried to do the right thing,” he said. “It seems like if you’re a good guy in this type of work and you’re willing to do the right thing—it’s almost like if you don’t toe the line, you’re going to be dealt with, one way or another. And if you do toe the line, you’re going to be living with the moral conflict of doing things you may not agree with.”