Growing human tissue artificially could be our best bet in replacing or restoring function to parts of the body damaged or lost by disease and injury. But it doesn’t have to be complicated. Sometimes all you need is a helping hand.

For a team of British scientists, that helping hand is a robot’s. Researchers at Oxford University, in collaboration with German robotics company Devanthro, have made a robot device that eerily looks like something straight out of Westworld. In a paper published Thursday in the journal Communications Engineering, this humanoid robo-shoulder is designed to help grow human tendons, soft connective tissues that attach muscle to bone. It may be to address those needs and be our ticket to regenerating these tissues more easily in the lab, helping millions of people in the U.S. who suffer from tendon injuries like rotator cuff tears.

As opposed to artificially growing organs like hearts and brains, finicky tissues like tendons need a bit more TLC to grow and function properly. The difficulties seem to be rooted in stretch and stress, Pierre-Alexis Mouthuy, a bioengineer at Oxford University and lead researcher of the new study, told The Daily Beast. Tendons, much like a growing muscle, need mechanical stimulation either from stretching being exposed to a weighted load. Exposing tendon cells to these forces influences how these cells mature, how viable they will be, and whether or not they will be able to function adequately or even be strong enough.

But currently, scientists don’t have a perfect system to satisfy a tendon’s unique mechanical needs. For the last 20 years, bioreactor technologies (devices that grow tissues) have only been able to stretch tendons in one direction—nothing like the sort of 360-degree paces or heavy lifting we put our tendons through every day.

The advent of robots, however, has changed all of that. In pursuit of growing a more perfect rotator cuff tendon in the lab, Mouthy and his team turned to Devanthro.

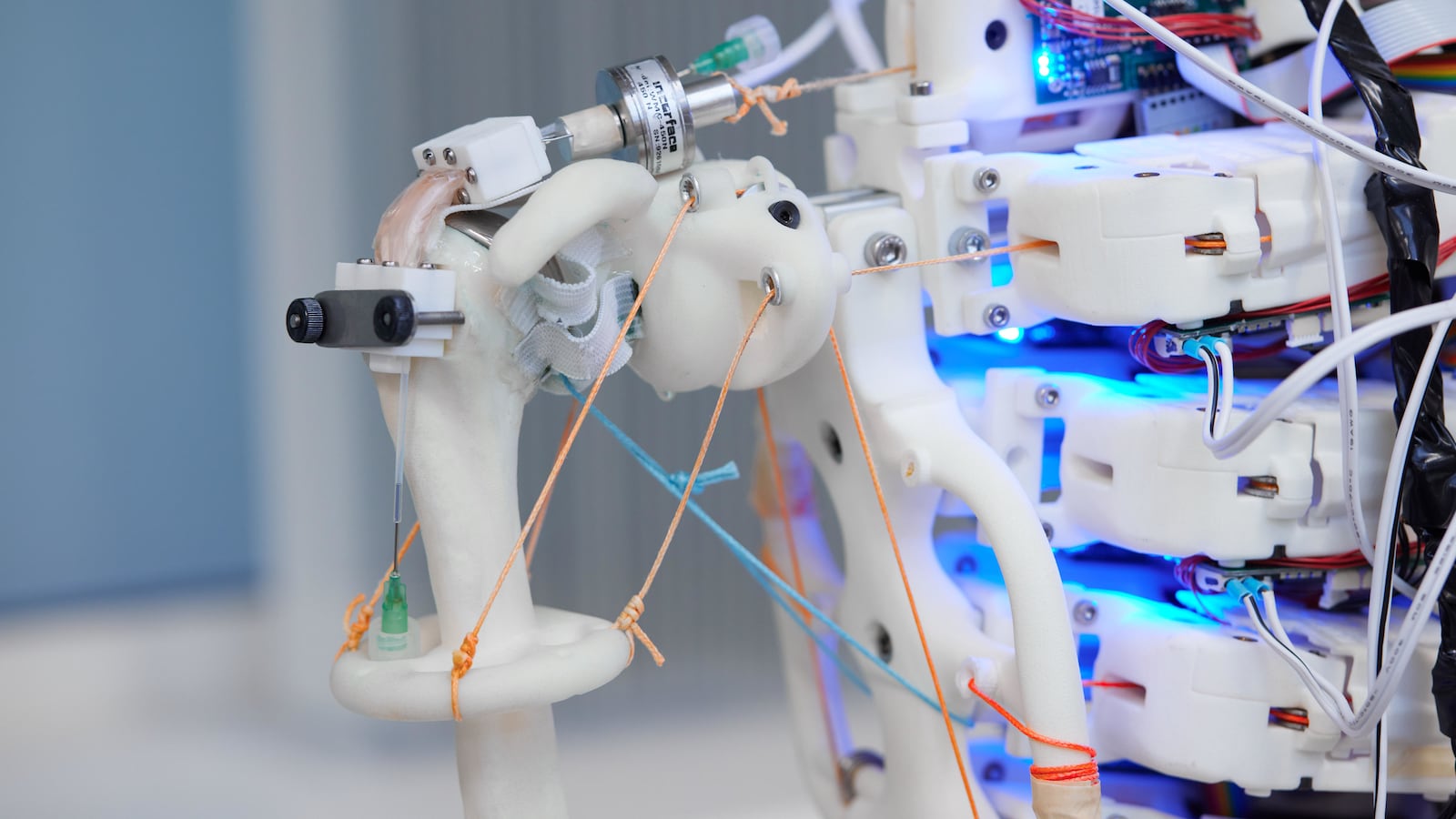

“[Devanthro] has developed these humanoid robots that use cords to move bone-like structures in a similar way to how the human body would do with muscles and tendons to pull on bone,” he said. “What we’ve done is modify that system, adapted it to create a sort of humanoid bioreactor.”

This humanoid bioreactor does look pretty human—it’s got a shoulder joint, part of an arm, and half of a ribcage with blue lights peeking through from all the hardware stuffed inside. The robot can nearly mimic the full range of human movements pretty well. Mouthuy and his team used it to successfully grow human fibroblasts (the principle cell of connective tissue) in just two weeks. They haven’t yet been able to grow a full-sized tendon, but the new results pave the path for researchers to start making human tendons very soon, particularly for people with rotator cuff injuries.

“Rotator cuff tears are very common—they can be the cause of trauma, bodily injury, or the result of disease,” said Mouthuy. “They are very age-dependent, so the older you are, the higher your risk of developing these tears.”

Typically, rotator cuff tears are repaired with surgery, but Mouthuy said a downside to stitching a tendon back up is that it’s not entirely a cure: It doesn’t improve a tendon weakening due to age or disease.

Mouthuy hopes this new humanoid bioreactor will make it possible to create tendons that not only replace torn rotator cuffs (or any other tendon injury), but also promote better healing and reduce the need for invasive surgery. The robo-shoulder may also help scientists better understand the relationship between different amounts and levels of mechanical stress and how these forces influence a cell’s gene expression and ultimately, what kind of tendon it becomes.

“There’s a need for providing better tissue grafts to the clinic,” he said. “Not just better tissue grafts but biomaterials that would help support the repair of soft tissues. This is what we are trying to achieve with tissue engineering.”