Flings: StoriesBy Justin Taylor

Perhaps the most immediately striking feature of Flings, a new collection of short stories from Justin Taylor (author of Everything Here is the Best Thing Ever and The Gospel of Anarchy) is the spectrum of the stories’ protagonists: in “Sungold,” a slacking pizza shop worker in a mushroom costume lusts after his fellow employees. In “A Talking Cure,” two over-educated PhD candidates go to lengths to harm their relationship with uncomfortable truths and then rebuild it with sexual exploration. And in “Carol, Alone,” a septuagenarian Florida widow regards her terrible loneliness with something approaching fascination, after an alligator appears at her doorstep. What unites these disparate characters is their sense of being harmed, or at the very least changed in ways that perplex them, by the passage of time. Cursed with intelligence and sensitivity, they are too keenly aware of what life has done to them, but not how it has done it, and their assessments of their internal states, wrought in Taylor’s often stunning sentences, can be devastating. Here is Carol, wondering at what her life has become: “Sometimes I feel like the hole in my life is even larger than my life ever was and that I live inside it, potted like a houseplant in the soil of my grief.” At the root of Taylor’s fiction is one the great ineffable questions, so simple as to come off almost silly when stated plainly—why are the current state of things one way rather than another? Unanswerable, of course, but this collection cements Taylor’s status as a young writer to follow.

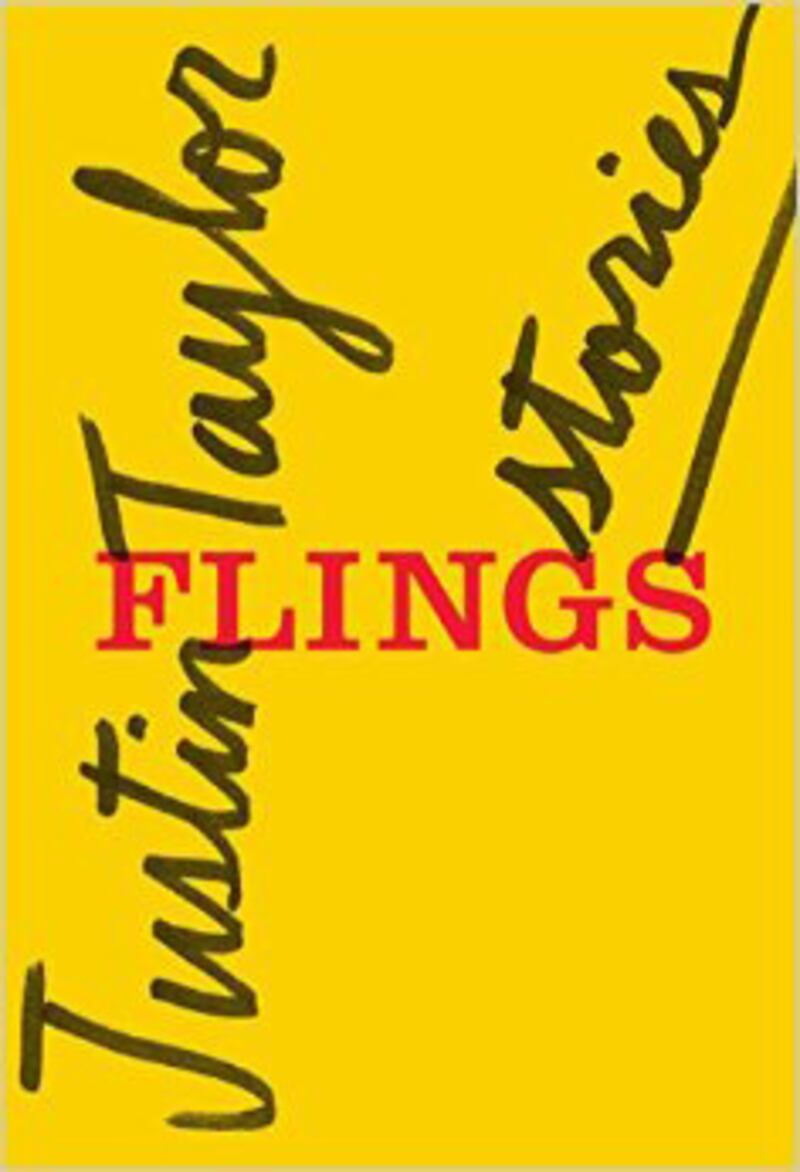

Blood Aces: The Wild Ride of Benny Binion, the Texas Gangster Who Created Vegas PokerBy Doug Swanson

Benny Binion, horse trader, bootlegger, life-long scofflaw, Las Vegas kingpin and then the popularizer of Texas Hold ’Em poker, combined two of America’s favorite tropes: the cowboy and the gangster. Cowboy in his do-it-yourself ethic, his ingenuity, and his down-home persona, and gangster in his ruthlessness, his avarice, and his uncanny ability to stay one step ahead of the law. In Blood Aces, Doug Swanson tells the story of a man who flat-out refused to make an honest buck in life, and lived high on the hog while doing it. For an aspiring con-man, there is plenty of inspiration here: Binion’s hustle, from when he first learned how to cheat a man into buying a sickly horse to his days running the Horseshoe Casino in the golden age of Las Vegas, is a thing to behold. But it’s the even darker strains of his character, of course, that will really captivate readers: his bloody feuds with his rivals can reach a near-farcical pitch, with one lucky (depending on how you look at it) adversary surviving double-digit assassination attempts before his luck runs out. Others were less resilient. Just one story of many—to highlight the lengths, or depths, that Binion would reach in his quest for money and power—has him personally and brutally murdering a rival by ambushing him in his car, and then (successfully!) claiming self-defense thanks to a “bullet scratch” under his armpit. This is, technically, a biography, but it reads like the best kind of crime drama- where you find yourself rooting for the bad guy.

Before, During, AfterBy Richard Bausch

At the narrative nucleus of Richard Bausch’s twelfth novel, Before, During, After, are two massive events so emotionally freighted, one on the most public scale and one on the incredibly personal, that in most cases the guard of the reader would rightly be raised—he thinks he’s a good enough writer to handle all this? Bausch, though, earns his subject matter, and proves he’s up to challenge. The novel centers around the love that arises between an Episcopal priest named Michael Faulk, on the verge of leaving the ministry, and Natasha Barrett, a woman in the employ of a senator. The two compare emotional scars, which Bausch fleshes out with great attention to pacing, and are soon caught up in what they think may be the grand second act of their lives, until the twin tragedies: first, terrorists fly planes into two tall buildings in New York, and then Natasha, in those first frantic 24 hours when she, like so many, was unaware of the fate of her loved one, is sexually assaulted on a beach in Jamaica. It’s a lot to handle, and would have been over-reach for a lesser writer, but Bausch pulls it off by displaying the utmost care for his characters, employing the highest form of authorial omnipotence to show how external horrors reverberate in internal spaces. Here is Natasha pausing to reflect on her life (or rather, Bausch doing it for her, transcribing the instant of a pang of feeling in his character’s heart, in other words doing the work of literature): “It had been such a good day. Yet she possessed the necessary detachment to admit that her emotions about it might be sentimental, that she could be producing them in some way, a self-deception born out of where she had been and what she had been through.” Masterful prose, in the service of a masterfully told story.