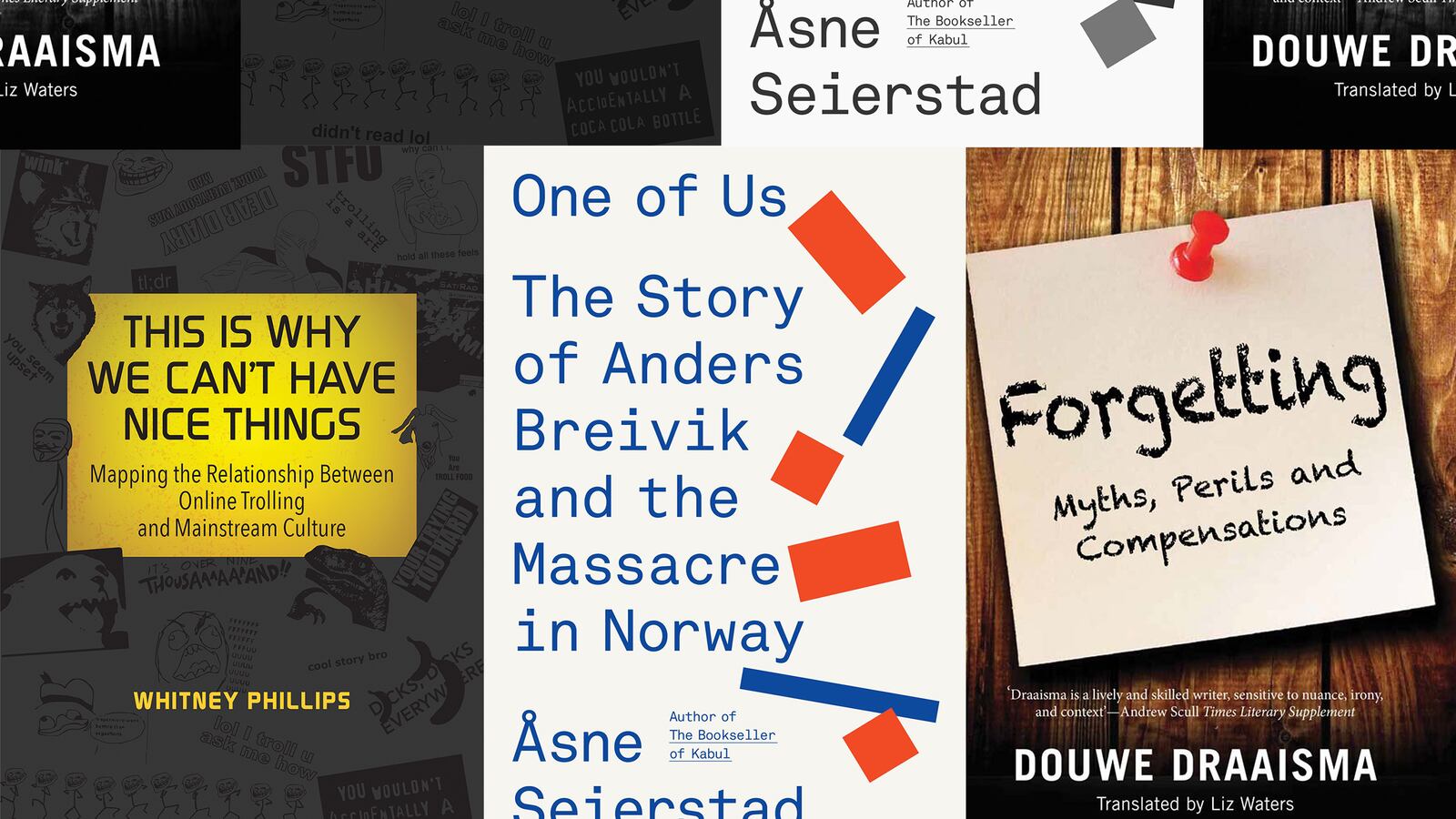

This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things By Whitney Phillips

If you are anything like me, you likely experience the internet in relatively honest terms. You read the news, check your email, speak to your friends, research something on Wikipedia… floating from webpage to webpage, ignoring what you dislike and attending to your desires. The world contained in the globally scattered servers feels, to me, like a world of little bubbles. But bubbles pop, and the world-wide-web can spill right out onto your doorstep. Your Facebook page, online banking, and other social media pages are all susceptible to those who know how to manipulate the systems, which have have become fodder for a new kind of bully.

In the 21st century, where virtual space is beginning to directly correspond to our physical bodies, the old-school jock bully has been eclipsed by a new paradigm. The people stirring up trouble between these two worlds are broadly known as “trolls.” And while the bully that steals your lunch money is still worrisome, it is now possible to withdraw funds directly from the source. But you knew all that. What you likely didn’t know is that this phenomenon has a long history that goes far beyond personal cyberbullying.

Trolls, Phillips argues, use social norms to identify the tensions between what is taboo and what is acceptable. They then park themselves on the threshold between the two and take pleasure in trying to drag you across the line through disingenuous arguments, baiting, and blackmailing. The surprising product of their mucking around in this space, and their subsequent congressing is well known to most internet users: memes, idioms, LOLCats, advice animals, etc.

This result, Phillips contends, is not so different from what passes as “legitimate” punditry from sensationalist media outlets. Perpetrators like Fox News use grandiose claims to get you to look and then spin up facts and invent narratives that were never intended to be truthful reporting but rather were meant only to make you keep watching.

Instead of looking for laughs at others’ expense, the goal is monetary. For example, demanding Obama’s birth certificate is not a news story—it does not inform or educate, and it implies a great deal of racism and xenophobia.

Phillips maintains that in the end this spin is very damning and only superficially separates itself from the the overt and over the top racism used by online trolls.

Trolls have become a part of the social fabric, our “agents of cultural digestion,” as Phillips puts it, and therefore, we should remain critically engaged with their output rather than merely lambasting and acting in an equally trollish way back at them… you will never troll the trolls.

One of Us By Asne Seierstad

Everything about Seierstad’s portrait of Anders Breivik is substantial, but nothing about it is easy.

Anyone today who embarks upon this story knows what lies ahead: that terrorizing Friday morning in 2011 when a car bomb exploded outside of the Norwegian prime minister’s office building killing 8, and that paralyzing afternoon where 69 young Workers Youth League (AUF) members were massacred on the island of Utoya. However, these horrifying hours do not convey the whole story so a genealogy of the event is necessary.

Anders Breivik may be easily caricatured, but he is just as easily misunderstood. On the surface he is a normal dressing, normal acting member of the Norwegian public. Upon closer inspection his life is filled with idiosyncratic moments. Although he grew up in a well-to-do part of Oslo, with nice schools where he appeared to have some friends and was clever enough to get by, the facade of the perfect Norwegian life crumbled there. What happened behind closed doors would make even the most skeptical observer cautious. Anxious neighbors and teachers recognized his oddities and petitioned social psychologists to observe the child, but nothing came of this.

Breivik’s monstrous ploy began many years later after an unsuccessful search for a venue to fit his grandiose self-image. Failure plagued his psyche and dominated his thought. Addicted to the World of Warcraft video game, he momentarily felt to have found his calling, but when it became doubtful that he would ever be the best, he turned away from the virtual and into the corporeal—the Progress Party (Norway’s ultra-conservative party), and further, to the seedy underground of anti-Islamist and anti-socialist web pages like the now infamous document.

In the end, there is not much one can say about a massacre, let alone one perpetrated in the name of racism, xenophobia, and juvenilicide. Even so, Seierstad’s book is a well-researched, well-written biography.

Breivik was charged with committing an act of terrorism and condemned to the “21-years” sentence—the maximum—with the possibility of indefinite extension. The crux of the trial was the sanity of Anders Breivik: was he responsible for what he did himself, or does his diagnosis mean that it was beyond his control? Seierstad shows us that Anders wanted full responsibility for his actions. In fact, he still demands it.

Forgetting: Myths, Perils and CompensationsBy Douwe Draaisma Translated by Liz Waters

Draaisma takes on all of the assumptions we make about memory.

Tracing the history of the idea, he concludes that the way that we think about memory is regrettably one sided. The problem is easily caricatured linguistically—we have many verbs for memory: to remember, to recollect, to recall, and the noun, memories, but what do we have to say for its counterpart: forgetting? We have many verbs, but no noun. So what is it, exactly, that forgetting does? What is it about the absence of memory, a concept framed entirely in the negative, that is so tricky? Surely, he postulates, there is much to be gained from rethinking this sticking point.

Working in the same vein as such authors as Oliver Sacks and Vilayanur Ramachandran, Draaisma builds on a series of case studies that brilliantly illuminate the concept.

Beginning with why we forget our dreams, Draaisma moves from cryptomnesia (a memory bias where one remembers something without it being recognized as a memory, but as an original idea), to prosopagnosia (face-blindness), Korsakoff’s syndrome, anterograde and retrograde amnesia, and many others, to illuminate the ways in which our brains retain and process information. He finds that we rely on forgetting just as often as remembering and it actually appears to be a saving grace for many people who suffer from harmful memories, like those with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. The idea of forgetting unhappy memories, to master the “dark art” is researched and explained in simple and relatively easy-reading prose.