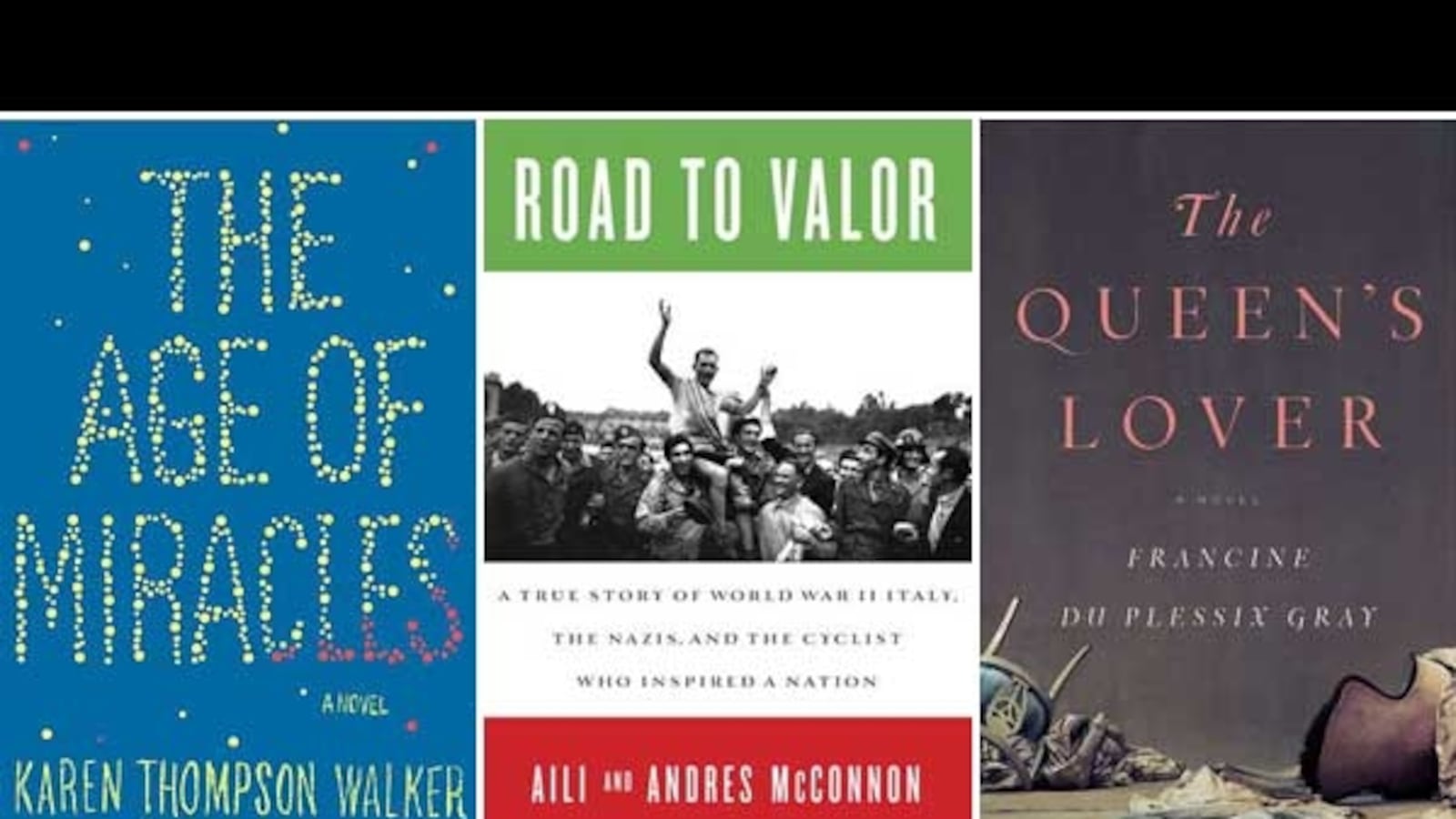

The Age of Miracles By Karen Thompson Walker

A novel of the apocalypse. As the Earth’s rotation begins to slow, a young girl gives us her account of the end of days—but does this debut have a sense of an ending?

The rotation of the world begins to slow, and the story of the end of days (at least, of 24-hour days) is told through the eyes of 11-year-old Julia. The test of apocalyptic fiction was devised by Frank Kermode in The Sense of an Ending, one of the most eye-opening works of literary criticism written in the past 100 years. As Kermode noted, it is one of the great charms of books that they have an end. “But unless we are extremely naive, as some apocalyptic sects still are, we do not ask that they progress towards that end precisely as we have been given to believe.” A great many surprises must open out in real life as in great fiction, or we descend into the rigidity of myth. There is much in The Age of Miracles’ plot that is like clockwork, as in tick, and then tock. There is not enough inventiveness between tick and tock to transcend preexistent types.

Yet there is a teasing revisionism in Walker, since the end of days is written not only as the struggle for survival but also a terrible bummer when Julia tries to maintain her crush on hottie Seth Moreno. There are also hilarious moments. “We were not required to squeeze our days into twenty-four little hours. No new law was passed or put into place. This was America.” And finally, there simply is no tock. Kermode would have loved that.

The Queen’s Lover By Francine du Plessix Gray

Near-perfect historical authenticity marks this triumph of scholarship and storytelling, about the lover of Marie Antoinette, by one of the most patient and prepared writers of our time.

Historical fiction is a tough gig. Soar too high above reality, and your readers’ wings melt; stay too close to simulations of historical authenticity, and there’s almost no point in taking off. Du Plessix Gray bypasses the problem by selecting a tale whose authentic facts are as deliciously intriguing as fantasy and conspiracy. It is the scandal of Marie Antoinette and her Swedish lover Axel von Fersen, a history not excessively well known yet not alien at all, which merely had to be researched, sorted, dated, and quoted in length for its marrow to ooze out. The august du Plessix Gray, now 81, has for her entire career bathed in the notoriety of the French romantics and proto-modernists (she has written biographies of the Marquis de Sade, Madame de Staël, and Simone Weil) and has waited her whole life to write this novel. It is a remarkable book.

Beyond the Blue Horizon By Brian Fagan

Why did early humans risk drowning in the depths of the ocean to venture out into the unknown? An archaeologist explains the allure—and the rationale of exploring—the blue planet.

Most of the world is under water; we humans, on the other hand, are land creatures. What made the first mariners rig a canoe and paddle out farther than one might be able to swim? It sounds awfully risky for Jason to get on the Argo. Archaeologist Brian Fagan charts the history of our quest to master the ocean, the great river that encircles the Earth. What made the Polynesians venture beyond their islands? (In fact, how did they get there?) Why were the Greeks such seafaring people? Why did the Norse not turn back and find a way to warmer climes, but instead map the North Sea and the coastline? Why did Blue Planet come before Planet Earth? Good questions, all of them.

The Road to Valor By Aili and Andres McConnon.

What sort of sports hero should we celebrate? Try Gino Bartali, two-time winner of the Tour de France who defied Mussolini and helped the Jews.

In America, we evaluate sports by numbers. Our heroes are recordholders. In cycling, we hail Lance Armstrong as the best, and enthusiasts worship Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx, Bernard Hinault, and Miguel Indurain—the club of five-time winners. The McConnons present to us the story of Gino Bartali, who, yes, had his records—he won the Giro d’Italia three times and won the Tour de France twice, in 1938 and 1948. Those 10 years between victories mark the largest gap in the history of the race. But it is the human aspect—in fact, the heroic aspect—of Bartali that warrants our deepest respect and adoration. He hated the Fascists and biked around the country couriering messages for the Italian Resistance—now that’s a bike messenger! He also hid a Jewish family in his cellar and saved their lives. Today, the sport is smeared with cowardice and scandal of the reality-show sort. Doping is merely the nefarious extension of pseudorobotic engineering of the wind-tunnel, composite-materials-obsessed kind that has overtaken a once joyous and scrappy sport. Bartali chain-smoked while he biked and drank glass after glass of Chianti the night before a race. This is the type of hero we ought to celebrate—a colorful and courageous human, full of life and the conviction of goodness.

A Fatal Debt By John Gapper

A debut thriller by an award-winning financial-news columnist taking a stand against those getting away with crimes on Wall Street.

How much of fiction should be useful? To what debt does fiction owe reality, or the news of the day? You might answer none, but even Marianne Moore said of poems, “These things are important not because a / high-sounding interpretation can be put upon them but because they are / useful.” The most prevalent concerns of our times has become the crimes and corruption of the financial crisis and the roots of inequality. Gapper, an award-winning Financial Times columnist, has dealt with those knots in his journalism for years, and now he’s bringing them forth in a debut thriller.

The story is about a psychiatrist in a New York hospital who had to treat a Bernie Madoff–like former Wall Street legend, but gets embroiled in a murder and conspiracy. Read it as standard Grisham, and it’s quite fun. The question is why Gapper, as well as fellow journalist John Lanchester (whose fourth novel, Capital, also surveys the landscape of the financial crisis), elect to use fiction as an agent of change. You might object, but they, like Moore, are perfectly right. Fiction is useful, and the novel even more so, since the form takes it upon itself to organize and balance regressive pleasures, to require the sense of realism and the progression to a predictable end—the tick, and then the tock. Gapper and Lanchester are making a sort of logical argument, and we should be wise to pay attention.