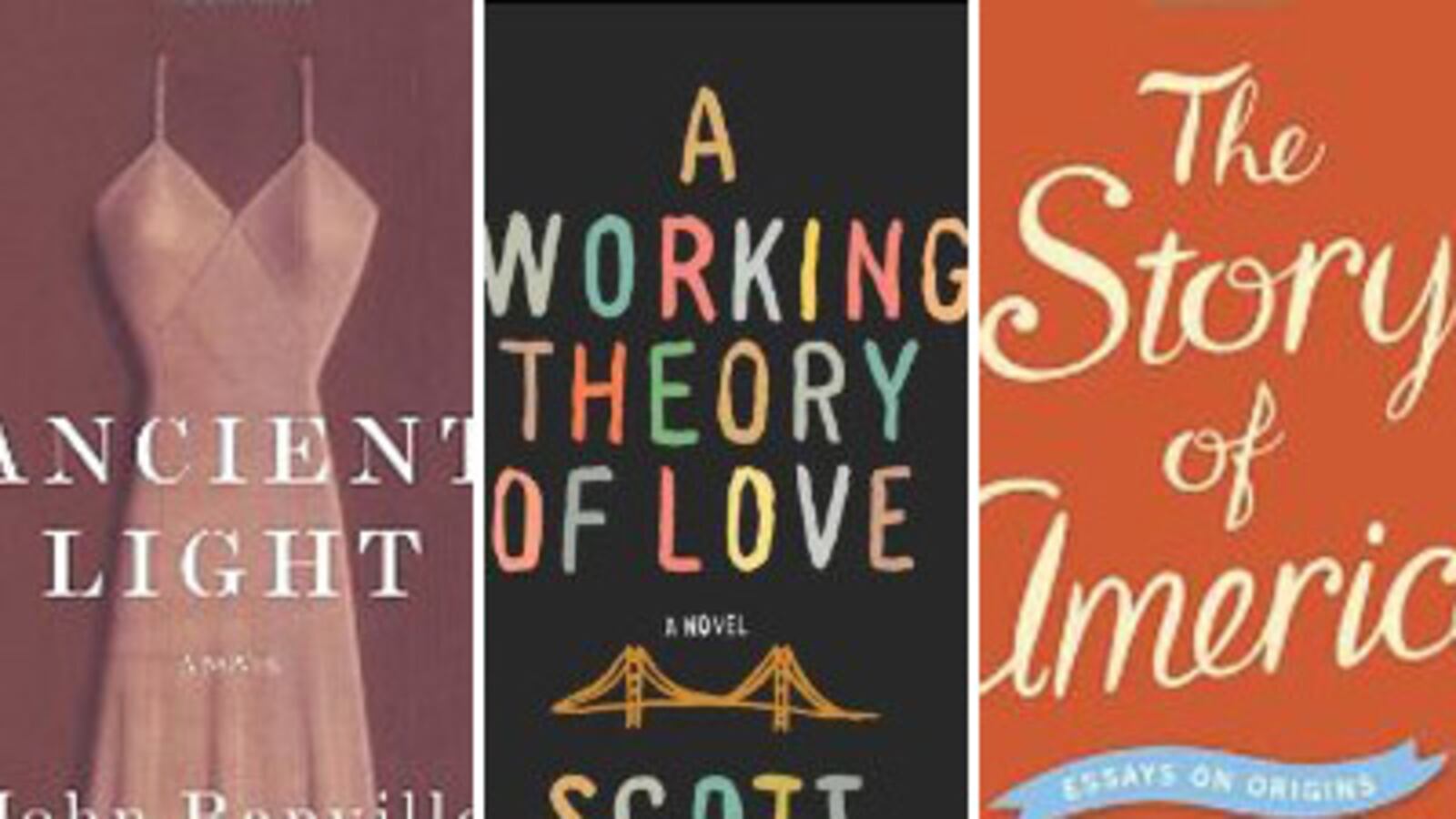

Ancient Light By John Banville A scandalous affair between a 15- and a 35-year-old is rendered as a gorgeous piece of literature in the hands of the Man Booker Prize-winning master.

To fully appreciate Ancient Light, you have to be familiar with Banville’s Eclipse and Shroud, which feature Alex Cleave, the man at the center of the (so far) trilogy, which hopefully will turn into a continent, something like In Search of Lost Time. Banville is the heir to Proust, via Nabokov, and not because there is a lot of sex in Ancient Light. In the book, Alex is remembering a love affair he had with his best friend’s mother—he was 15, she was 35. But the very act of remembering is so soaked in the senses that, like Proust, it goes beyond recalling and enters the sphere of reliving and creating. For one, Cass, Alex’s daughter, appears only briefly in the new volume, but as the tragic heroine of Shroud her ghostly translucence haunts the Banville reader, and altogether the three books leave a lasting glow. Nabokov, in his Lectures on Literature, noticed the gorgeous emanating of light and color in Proust: "This band of light was of a mauve color, the violet tint that runs through the whole book, the very color of time.” In Ancient Light, Alex tells us that as a child he used to have insomnia, so his mother let him sleep in a sleeping bag on the floor next to her bed. “She would reach out a hand, too, from under the covers, and give me one of her fingers to hold.” Later, when his scandalous love affair was revealed, Alex found himself again in his mother’s room. “The light around the curtain was stronger now, a light that seemed somehow to shake within itself even as it strengthened, and it was as if some radiant being were advancing towards the house, over the grey grass, across the mossed yard, great trembling wings spread wide, and waiting for it, waiting, I slipped without noticing into sleep.” Beautiful.

Silent House By Orhan Pamuk Newly translated, the second novel by the Nobel laureate takes us into the minds of Turks forced to take sides between the nationalists and the communists.

There is a grandmother who lies awake at night remembering her youth and her late husband in Pamuk’s second novel, translated into English at last. Her three grandchildren, Faruk, Nilgün, and Metin, visit her mansion in a town near Istanbul, her “silent house.” The dwarf servant, Recep, who’s actually the late husband’s illegitimate son, takes care of the family, and his nephew Hasan has recently joined a nationalist gang. It is 1980, and in weeks a coup would put the military in charge for three years, ending the armed conflicts between the nationalists and the communists. But in the few days over which Silent House takes place, dark clouds are very much gathering. It all climaxes in an act of inexplicable violence that has less to do with politics than the emotions and passions that such senseless ideological wars whip up. Pamuk is Turkey’s national author, and Silent House is particular about its place and time. But the story in this somber little book can probably happen in any divisive atmosphere. Each chapter is narrated by a member of the household—Recep, the grandmother (Fatma), Hasan, Faruk, or Metin—and in so doing Pamuk shows the love and care he has for people with different ideas and preoccupations. He never succumbs to stereotypes—Hasan, Faruk, Metin, and Nilgün are all youths, but the universe inside their minds is rich and complex. Even the grandmother, who’s abusive to Recep, has glorious remembrance of things past. Fanatical ideologies might occupy our heads and empty them of their contents, but it is literature like Pamuk’s that returns humanity to the silent house.

The Story of America By Jill Lepore A collection of essays by the Harvard academic who’s taken up the task of revitalizing and refreshing American history.

Lepore is a Harvard historian, but she’s not above pointing out just how snooty we think Harvard historians are. “Samuel Eliot Morison, the last Harvard historian to ride his horse to work,” so begins one of her essays about how Pilgrims and Puritans are portrayed, immediately allowing us to chuckle at the thought of the man stuffing his saddlebag with papers to grade. Her point is clear: she walks among us. Lepore loves to go to gun shows or wacky Dickens conferences to report on the hobbies and passions of ordinary Americans. She might be the historian most willing to leave her comfort zone, which makes her a first-rate reporter in the pages of The New Yorker, where she is a staff writer. In this collection of her essays from the magazine, she paints portraits of George Washington, Thomas Paine, Longfellow, and many forgotten figures in America’s founding, rescuing them from dogmatic myth to show that they are as human and as able to surprise as your best friend is able to inspire and infuriate you. Her best essay might be “Pickwick in America,” which chronicles Charles Dickens’s disastrous (for his own public image) trip to the U.S., after which he would write American Notes, a book that many consider to be Dickens’s worst. The story is the centerpiece of the collection, but it is based on a rather minor episode in a great writer’s life, and it is a profile of the most English of English authors in a book titled The Story of America. The ingeniousness of it is Lepore’s ability to show you that Boz’s view of the country helped create our collective idea of America as much as Washington or the Tea Party did. Lepore knocks you out of your comfort zone. You thought you knew America? See how it’s defined by the scraps of a Brit! Dickens showed the land to be “a troubled republic: ambitious, cruel, ungenerous, brutal, and divided.” Some things never change.

The Last Viking By Stephen Bown A giant in the heroic age of exploration, the Norwegian Roald Amundsen was perhaps the greatest adventurer of them all as far as brute achievements go. Then he vanished.

When the ill-equipped British explorer Robert Scott reached the South Pole on Jan. 17, 1912, exhausted, starving, and freezing, he thought he was the first person to achieve the feat, only to find that the well-funded and savvy Norwegian Roald Amundsen, the first man to navigate the Northwest Passage, had already been there. Londoners fumed that Amundsen had committed “a dirty trick altogether”—he had tried to sabotage Scott’s order for huskies, and kept his plan to race Scott to the Pole secret, not even telling his team where the real destination was. It didn’t help that Scott and his four companions all died, from exhaustion, starvation, and the cold, on their return journey, thus securing their place in martyrdom. Amundsen was reviled, and then ignored. But he went on to navigate the Northeast Passage as well as reach the North Pole in a record-breaking flight at the age of 53. His reputation was salvaged, and in 1928, at the age of 55, he joined Scott in the ranks of myth. While on a mission to rescue the Italian crew of an airship that had crashed while returning from the North Pole, Amundsen’s flying boat disappeared in a cloud of fog. He was never seen again.

A Working Theory of Love By Scott Hutchins A son creates an artificially intelligent computer based on the journals of his father, who committed suicide some years ago.

Neill Bassett is helping the artificial-intelligence company Amiante Systems create a computer that’s based on his father, Dr. Bassett, who left behind thousands of pages of journals that are perfect for animating a nonthreatening machine that might or might not beat the Turing Test to become a truly intelligent, sentient being. Add the fact that Dr. Bassett was an unhappy man who killed himself a few years before, and the premise could make a dark and penetrating take on the old tale of a son reconnecting with a father. The other preoccupation of the novel is Neill’s efforts to find love after his young marriage dissolves. He is unable to get over his ex-wife as he meets other women, and we are supposed to feel sorry for Neill. Yet Neill is himself a rather nonthreatening man, sad and nonchalant, so much so that he is far less interesting and human even compared to a computer! Ultimately, Hutchins doesn’t explore the father/son and machine/human relationship very deeply, and the romance only serves as a “will he find love?” device—of course he will. But Hutchins proves a good programmer of thought-provoking experiments, as when Neill has to decide what to do with Dr. Bassett when Amiante Systems is sold. Does he unplug the machine, assuming his father would and did chose suicide? Or does he go against his wishes? He does answer that question, but the best philosophers, like Alan Turing, realized that the question was infinitely more important than the answer.