This morning, before writing about Alice Munro, who has won the Nobel prize for literature, I took down from the shelf a couple of volumes of her short stories, thinking to thumb through them and refresh my memory (or maybe I was just stalling, awed, or merely stymied, by the prospect of summing up a life’s work in a few paragraphs). Two hours later, I looked up, wondering where the time had gone. I suppose that when people talk about a writer casting a spell, this is what they mean.

Certainly this is what happens whenever I pick up one of Munro’s extraordinary stories. I get lost, time stops, and I emerge at the end like a man coming out of a movie theater in the middle of the afternoon, blinking in the sunlight, shocked by the suddenly sharp, hard-edged reality of the ordinary world.

There’s a difference between those experiences, though. Moviegoing displaces everyday reality, or banishes it for a couple of hours. Munro’s stories stop time, too, but when you’re done, the world you awake to seems enhanced somehow. Every mundane detail seems important, as though she’d crept up behind you, taken you by the shoulders and given you a good shake, as though to say, “Pay attention. There’s no telling what you might see around the next corner.”

One of the stories I looked at this morning was the title story in her most recent collection, Dear Life. It is one of four stories at the end of that volume, stories that she segregates from the rest with a note: “The final four works in this book are not quite stories. They form a separate unit, one that is autobiographical in feeling, though not, sometimes, entirely so in fact. I believe they are the first and last—and the closest—things I have to say about my own life.” That word “closest” stops me every time. Closest as in “closest to her heart,” or something clutched, or something unvarnished, artless, some plain truth? As always, mystery and specificity go hand in hand.

Frankly, the story I read seemed remarkably like a piece of Munro’s fiction. Feeling deepened as the story progressed, turning this way and that, details that seemed random at first took on weight, or depth, as the story went along. Her parents became more and more complex, like figures in a photograph slowly emerging in a darkroom developing tray. And the crazy woman who came up their driveway one day when Munro was an infant, who rummaged in the baby carriage from which little Alice had been snatched by a fearful mother who cowered in the house while the woman went around peering in all the windows—that woman too becomes more human as the story goes along, transformed from fairy tale witch to a more pitiable displaced person looking for her old home and her children in the house—once hers—now occupied by Munro’s parents. “Dear Life” may be raw truth or mostly fiction, but it feels utterly real.

At one point, when Alice is still a child, her mother forbids her visiting a friend nearby, because, it comes out a few years after, the friend’s mother had been a prostitute. “My mother told me this a long time later, or what seemed a long time later,” Munro writes, “when I was at the stage of hating a good many things she said, and particularly when she used that voice of shuddering, even thrilled, conviction.” The strains of adolescence have rarely been summed up so succinctly. But conveying a world in a line is something Munro does without breaking a sweat: both her parents came from farming families, but they had aspirations; Munro’s mother “had become a schoolteacher, who spoke in such a way that her own relatives were not easy around her.”

Munro grew up in the thirties in small towns around Lake Huron in Canada. Her father raised silver foxes and later minks. “There was quite a lot of killing going on,” she reports, what with old horses to be slaughtered to feed the foxes, and foxes and minks to be culled from the herd. But Alice was already flexing her imaginative muscles. “Fresh manure was always around, but I ignored it, as Anne must have done at Green Gables.”

Cynthia Ozick has called this peerless master of the short story “our Chekhov.” Richard Ford, contrapuntally, notes, “One could suppose that she’d easily be just a ‘writer’s writer’: arty, lapidary, secret-keeping. But no. She manages to make the best of literature and literary impulse irresistible to a general readership.” In a world where life is more fair, the Nobel would have been inevitable.

Set mostly in small towns in the author’s native Canada, Munro’s stories (she has only written one novel) record what we casually think of as the everyday actions of normal people. But she has an unerring talent for uncovering the extraordinary in the ordinary. In “Carried Away,” one of her greatest stories, a small-town librarian is jilted by a soldier returning from World War I, who is later decapitated in an industrial accident. The woman marries the town tycoon. Years later, a widow, she is visited by the ghost of her dead lover. Everyone in this story is consumed by a thirst for certainty, and this unslakable desire drives each of the characters further into the mysteriousness of life. Near the end of the tale, after the woman, now old, has encountered the ghost, she realizes that “it was anarchy she was up against—a devouring muddle. Sudden holes and impromptu tricks and radiant vanishing consolations.” The story finishes by circling back to the day the woman first arrived in town. “She had never been here when the leaves were on the trees. It must make a great difference. So much that lay open now would be concealed.” The beauty of this image and the bleakness of its meaning hang suspended in perfect balance.

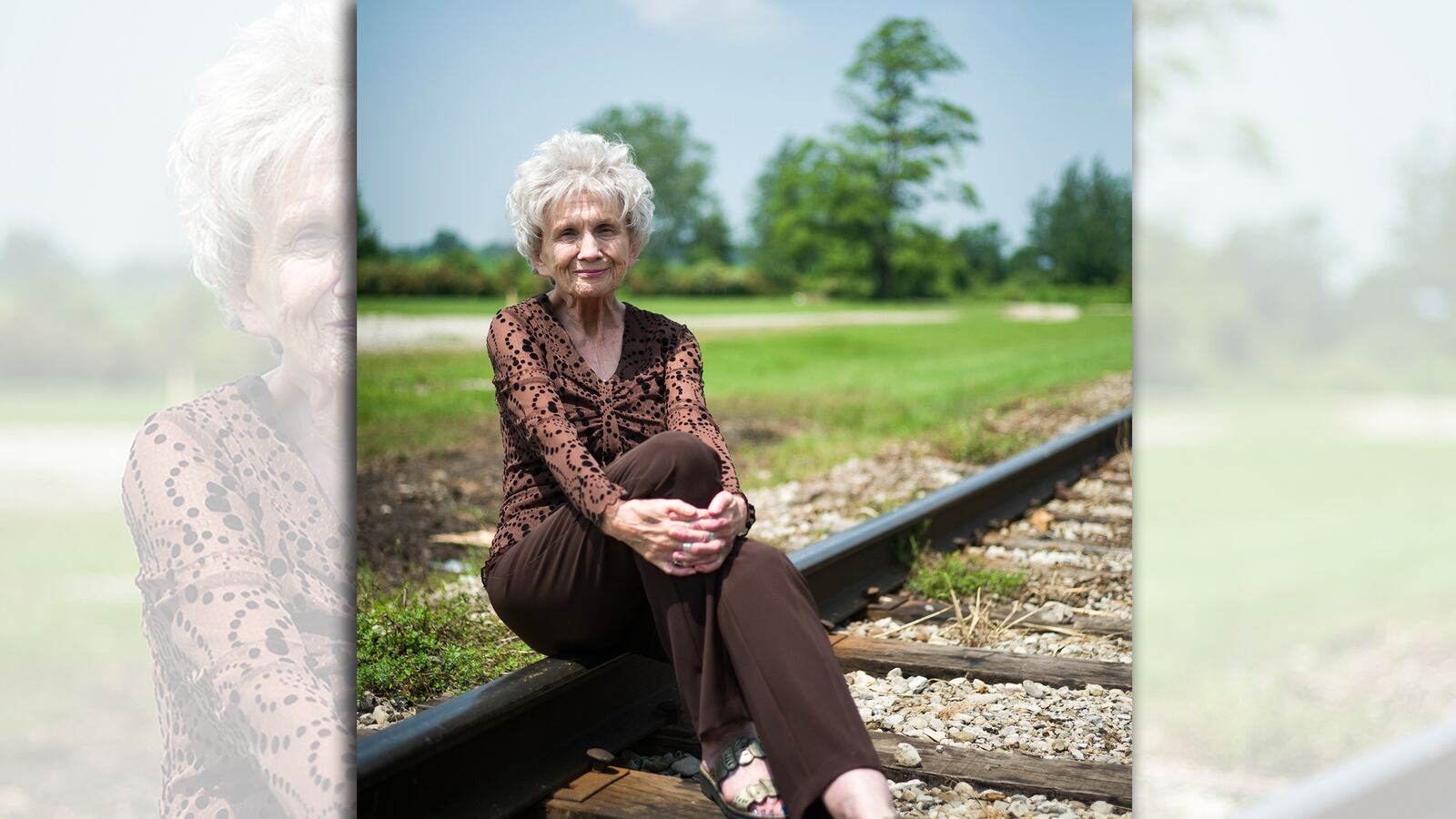

I interviewed Munro once, in 1996, when her Selected Stories was published. Over lunch in a Toronto café, she proved sharp, funny, forthright, and unassuming. “I’ve had the ordinary life of a woman of my generation,” she said, “housework, kids and all that. I’m not a very radical sort of person.” The bourgeois life was a conscious choice: “If you live an interesting life you probably don’t have much time to write.” I asked her if she did not feel as if she were just masquerading as a normal, middle-class person. “Oh, yes,” she said, laughing. “That wasn’t hard for me at all. I’ve been doing that since I was about three years old.”

Certainly the uneventfulness of her outward circumstances belies the intensity of her interior life. “I would have given up anything to be a writer when I was a teenager,” she said. “I’d have given up boyfriends. I’d have given up the whole of ordinary life to make this other world.” As a youth, she read everything she’d “ever heard of that had a reputation,” but it was Eudora Welty’s stories in The Golden Apples that set her course. “There was some transcendent importance that it gave to life,” she said. “I was crazy about that book, crazy to do that.”

When I quoted one reviewer, who called her stories “gossip informed by genius,” she said, “I love that. I read People magazine not just at the checkout stand, I sometimes buy it. Gossip is a very central part of my life. I’m interested in small-town gossip. Gossip has that feeling in it, that one wants to know about life.”

Munro’s stories are like life with the lid pulled off so you can stare at the works, and they are powered by a ruthless, unblinking honesty, an honesty that she extends to her own circumstances in those last stories in Dear Life. The title story closes with this paragraph: “I did not go home for my mother’s last illness or for her funeral. I had two small children and nobody in Vancouver to leave them with. We could barely have afforded the trip, and my husband had a contempt for formal behavior, but why blame it on him? I felt the same. We say of some things that they can’t be forgiven, or that we will never forgive ourselves. But we do—we do it all the time.”

Nobody takes your breath away like Alice Munro.