Books

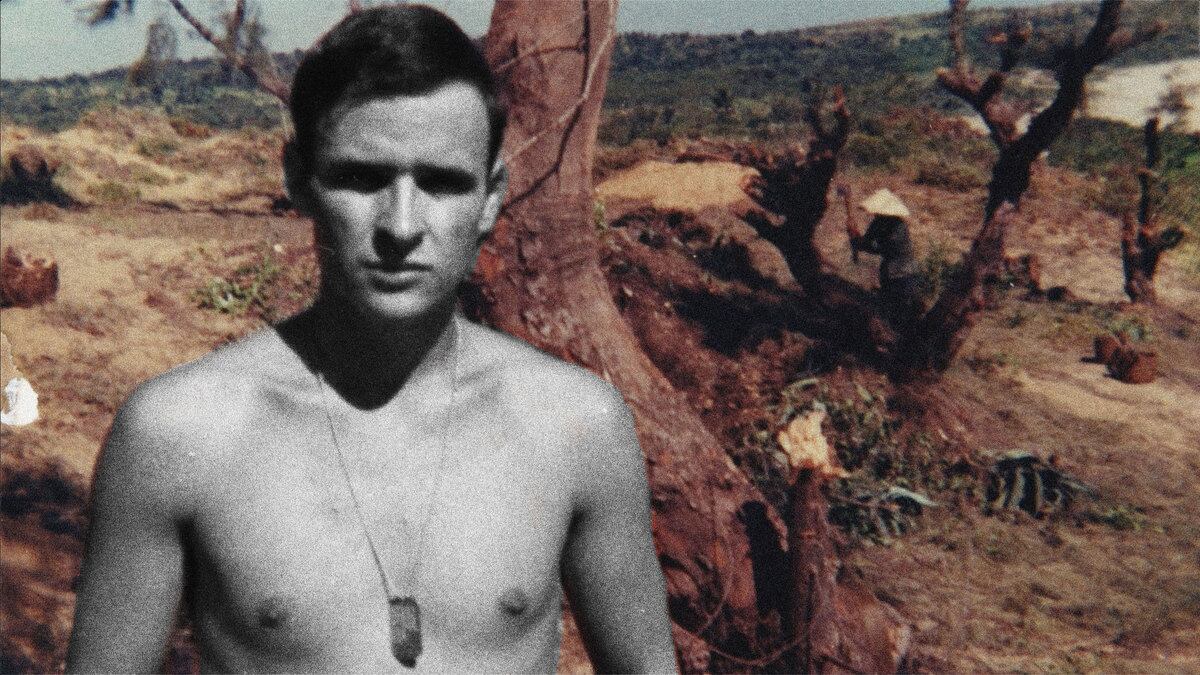

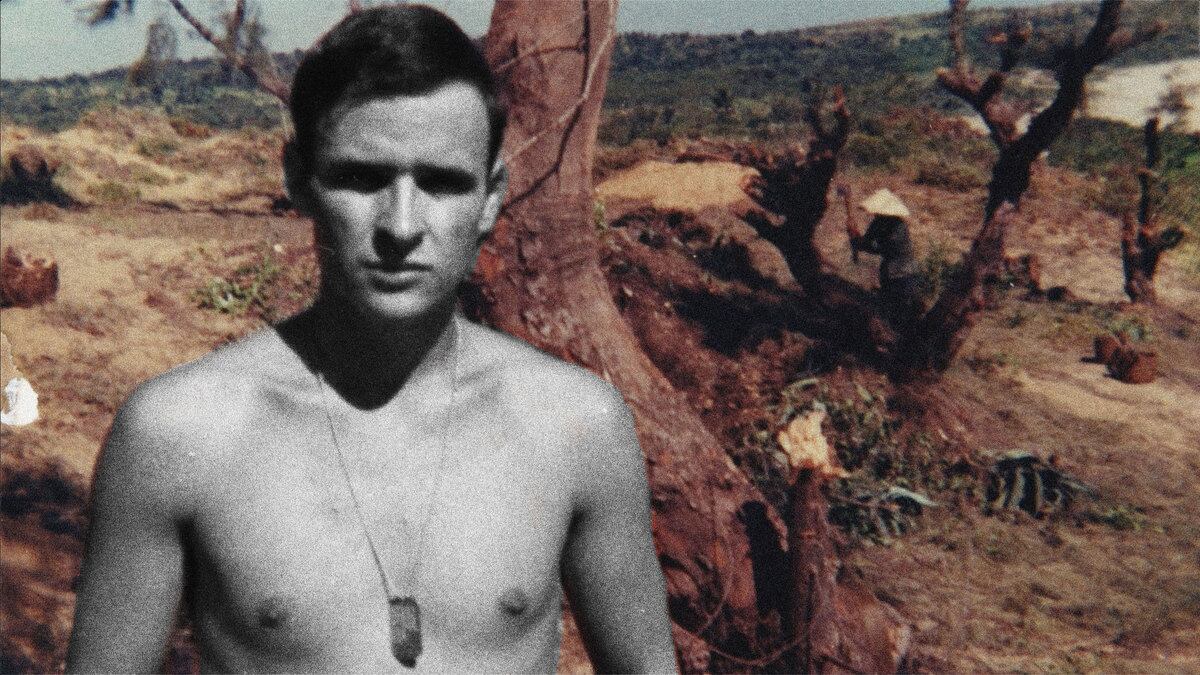

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast/Gravitas Ventures

Tim O’Brien on Anti-War Writing: ‘Sentences Don’t Do Shit.’

BRUTAL MESSAGING

“We are never short of reasons to kill people,” the acclaimed author says, “and books do not satisfy our appetite for killing.”

Trending Now