Where does one start to tell the story of Toto Koopman? Should we start in Paris, in the ateliers of Coco Chanel and the studios of French Vogue, where a 19-year-old Toto preened for the grand Jazz Age couturiers? Or perhaps in Britain on the brink of another world war, where Toto flitted among three of the country’s most powerful men?

Do we start in the prisons of northern Italy, among Mussolini’s anti-Fascist enemies? In the London gallery where avant-garde artists like Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud sold their scandalous works? In the green rice paddies of Java? In the lemon groves of Sicily? In the hell of a camp called Ravensbrück?

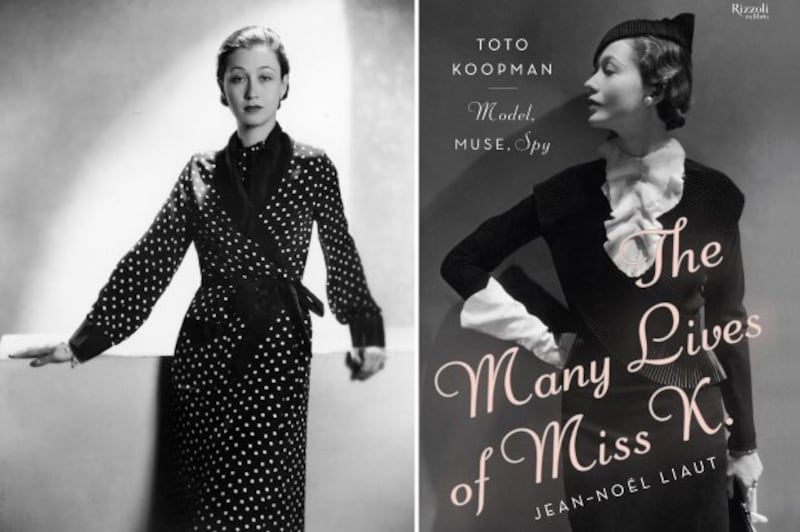

Now largely forgotten, Toto Koopman was one of those see-and-be-seen It girls of the early part of the 20th century—a woman who, with her striking good looks and insouciant charm, swirled about in the eddies of European high society, befriending (and seducing) some of the most remarkable characters to shape the continent’s wartime culture and its political destiny.

She dallied with media moguls, palled around with ambassadors’ wives, and bedded Hollywood actresses and war heroes alike. She also served as a spy for the Allied Resistance and survived the horrors of the Nazi death machine. Now her cinematic life is getting the hagiography treatment in a fascinating and flawed new book, The Many Lives of Miss K, out from Rizzoli this week.

The biography, by French journalist Jean-Noël Liaut, suffers a bit from breathless adulation of its heroine, as well as a frustrating lack of access to Toto’s own voice. (The author interviewed several late-life friends of Toto’s, along with some relatives, but he presents only a few letters between Toto and her closest contemporaries. As a result, the book tends to gloss over some of her more interesting pre-war episodes.) But Liaut is by no means alone in his extreme Toto infatuation. Indeed, he’s just the latest in a long line of men and women who found themselves besotted with the green-eyed model once described as “Ava Gardner’s double.”

Yet Toto’s early years hardly hinted at her future as a grande séductrice. Born in the volcanic foothills of the East Indies in 1908 to a colonel in the Dutch cavalry and his half-Javanese wife, Toto—real name Catharina—got her nickname from her father’s favorite horse. Despite the nascent stirrings of nationalism and resentment of Dutch rule percolating in Indonesia at the time, Toto led a typically colonial childhood. Her family lived in luxurious officers’ quarters amid tea plantations and tropical gardens, tended to by a fleet of Javanese servants and nannies. It was a world of white linen, afternoons spent horseback riding (sidesaddle for the ladies) or swimming in cool mountain pools, and military fêtes by torchlight. It was a world far removed from the Great War ravaging the motherland.

By 1920, Europe had entered into a tenuous peace, and Toto left Java to attend boarding school in the Netherlands. The teen had a talent for languages—she quickly became fluent in French, German, English and Italian—and began to ripen into a sensuous and fashionable young woman. She also had a taste for the independent life, so after a year of finishing school in England, the 19-year-old Toto arrived in Paris to make her way as a model (a profession that fell, at the time, “somewhere between a cabaret dancer and a tart”) and enjoy the raffish café society that had gripped the entre-deux-guerres capital.

Installing herself in the 17th arrondissement, a rough-and-tumble neighborhood of starving artists and nightclub singers, Toto was soon hired as a house model for Coco Chanel, though she left after a mere six months. (Later, she said she didn’t like the way the intense, demanding Chanel touched her during fashion show fittings.) But Toto’s career began to gain momentum on its own. She served as mannequin and muse to the designers Rochas and Mainbocher, wearing their elegant creations to nights at the opera and grand galas about town. She became a favorite of Vogue photographers Edward Steichen and George Hoyningen-Huene, an émigré baron who had fled the Russian revolution and who became a seminal force at the French edition of the magazine. Hoyningen-Huene cloaked her in minimalist creations by the likes of Vionnet and Augustabernard, clothing so sheer that Toto had to powder her intimate parts to keep the fabric from clinging indecently to her curves. “We were all exhibitionists, show-offs,” Toto reminisced years later. “One dressed up not to please men, but to astound the other women.”

Still, plenty of men seemed pleased and astounded by the biracial beauty. By the early 1930s, Toto had fallen in with the Mdivani brothers, a trio of bogus “princes” and petty aristocrats from the ruined tsarist court whose party antics and playboy conquests were the talk of Paris. While the boys parlayed their dark good looks into advantageous marriages with socialites and film stars, their two sisters managed to ensnare the son of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the Catalan painter José Maria Sert, whose passionate ménage à trois with the elder Mdivani girl formed the basis for Jean Cocteau’s play Les Monstres Sacrés. Toto befriended Nina Mdivani, the youngest of the clan, and entered into a wild affair with her impulsive, alcoholic brother Alexis, who was married to an Astor at the time. (He would later wed Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton before being decapitated in a horrendous car accident in 1935 at the age of 30.)

As colorful as the Mdivanis were, Toto’s other friends in Paris were equally audacious. Her fellow model Lee Miller swanned about town with her lover, the surrealist painter Man Ray, staging outré gags like carrying around a dissected breast, along with a knife and fork, on a plate. Toto was also close to the poet Caresse Crosby, who with her second husband, Harry, ran the Black Sun Press, publishing the works of Ernest Hemingway, D.H. Lawrence, and James Joyce, and who hosted elaborate soirees-qua-orgies at their Rue de Lille apartment, where the couple courted guests from their bathtub.

Another friend was Bettina Jones, the American wife of a high-level French politician and future ambassador for the Vichy regime, who fraternized with Salvador Dalí and who kept a vicious little monkey, clad in a tiny Schiaparelli coat, by her side at all times.

The high life in Paris was heady, but like many glamorous young women, Toto felt her future lay in the movies. She traveled to London, where the Hungarian director Alexander Korda was auditioning would-be starlets for bit roles in the upcoming Douglas Fairbanks flick The Private Life of Don Juan. After securing an introduction through a mutual friend, Toto was cast as a Spanish inamorata. None of her scenes made it into the final version, and Toto dropped out of filming halfway through, apparently bored by the endless takes and retakes. But she still attended the movie’s premiere on the arm of a flamboyant new lover, the American actress Tallulah Bankhead, famous for her mordant wit and voracious appetites. (“My father warned me about men and booze,” Bankhead liked to tell people, “but he never said anything about women and cocaine.”)

The bourbon-drinking Broadway star had recently been branded “an extremely immoral woman” by MI5 after she dabbled in “indecent and unnatural practices” with six Eton schoolboys, including the sons of a lord and a baronet. “It is also said she ‘kept’ a [black female lover] in America,” the Home Office noted in a confidential memo on the Bankhead scandal, “and she ‘keeps' a girl in London now. As regards her more natural proclivities, [an] informant tells me that she bestows her favours ‘generously’ without payment.”

Tallulah and Toto’s tryst lasted only a few months, but it was enough to change the course of Toto’s life. During that time, Bankhead introduced the 25-year-old ingénue to a billionaire whose shadow would loom large over Toto’s future and her wartime activities.

The 55-year-old Lord Beaverbrook, a Scottish-Canadian press tycoon né William Aitken, had clawed his way up to the highest echelons of political influence through a combination of tabloid blackmail, strategic alliances, and an unquenchable thirst for power. As the owner of the widely read Daily Express, Sunday Express, and the Evening Standard, he held sway over the reputations of Britain’s most illustrious parliamentarians and public figures. Winston Churchill derisively called him “Machiavelli,” and Evelyn Waugh immortalized him as the imperious Lord Copper in Scoop. Serving as minister of information during World War I, the deeply paranoid Beaverbrook developed a taste for intelligence gathering; later, he would employ private spies to tail the movements of his wife and children.

He took Toto as a lover in 1934, and she apparently began to eavesdrop for him in Germany and Italy, under the guise of traveling the seasonal opera circuit. The multilingual Toto mingled with Nazi elite and even reportedly had an affair with Mussolini’s son-in-law, all the while taking notes on the inner circles of Fascist intrigue. It was an advantageous relationship for Beaverbrook, but it was soon ruined by one of his own family members.

A year into their affair, Toto began carrying on in secret with the mogul’s son, Max Aitken. Max was as handsome and athletic as Beaverbrook was ambitious and cunning, an aviator with the royal air force and a notorious cad. When Beaverbrook found out about the clandestine dalliance, he was enraged. Worse still, Max was rumored to be giddily in love and ready to propose. Beaverbrook banned his newspapers from mentioning Toto’s name and threatened to disinherit Max if the marriage went through. When that failed, he offered to pay both Toto and Max large pensions if they signed a contract promising not to wed. “He told Max, ‘I’ll give you a lot of money if you promise not to marry that girl,’” Toto later recalled. “I said [to Max,] ‘Take it!’ So he did, and we had a wonderful time.”

Toto and Max used the cash to shack up in a luxe penthouse on Portman Square and became a much-desired society couple. Their relationship was an open one; Max kept a string of lovelies on the side, while Toto seduced Max’s friend Randolph Churchill, the spoiled son of the future prime minister.

After four years of frivolity, Max and Toto parted ways. He would go on to become a war hero as an RAF fighter pilot and, in the mid-1940s, a member of Parliament. Meanwhile, in the autumn of 1939, Toto headed south to Italy to rendezvous with some art collector friends. In Florence, she fell for a leader of the Italian Resistance and worked her social connections to help finance his anti-Mussolini activities. She also infiltrated Black Shirt meetings to send reports back to Max and the British government. By 1941, the police had caught on to her stratagems and arrested her “under the old pretense of being Beaverbrook’s mistress,” Toto wrote to a friend. “But once I was in jail … what they wanted was to free me and I was to do some terrible dirty work…of course, I refused flatly.”

Toto was shipped off to rundown prisons in Milan and Lazio before finally escaping from the Massa Martana detention camp and hiding out in the mountains of Perugia. From her refuge, she helped other former detainees connect to Resistance networks and make their way to safety. After being briefly recaptured by the Fascists, Toto fled to Venice, where an aristocratic friend smuggled her into a secret suite at the Danieli Hotel. One night, the friend learned that the Germans intended to search the premises to ferret out spies. In a brazen gambit, the aristocrat threw an opulent dinner for the German general in charge of the operation and seated him directly next to Toto. Dressed to the nines and flirtatious as ever, Toto was so conspicuous that it never occurred to the Germans to suspect her.

She survived the raid, only to be informed upon and rearrested within a matter of weeks. Infuriated by the double-crossing debutante, the Italians sent Toto to a much grimmer location: the all-female concentration camp of Ravensbrück in northern Germany.

The largest women’s-only camp in the Third Reich, Ravensbrück housed a mix of political prisoners, gypsies, Jews, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and “race defilers,” a term the Nazis used to describe Jewish women suspected of past sexual relations with Aryans. Situated on a marshy plain 50 miles north of Berlin and surrounded by electrified barbed-wire fences, the camp served as one of the main training centers for female SS guards. Prisoners were forced to manufacture components for German rockets, construct new roads, work in the brothels of nearby men’s camps, and mix the ashes from Nazi crematoriums with fecal matter to produce agricultural fertilizer.

Ravensbrück was terribly overcrowded and unsanitary—typhus and cholera epidemics regularly swept through the vermin-infested barracks—and after 1943, conditions rapidly deteriorated. Food rations became severely restricted, with each woman receiving one piece of bread and a cup of fetid soup per day, and prisoners too weak to work were gunned down en masse or euthanized. All told, of the 130,000 women to pass through Ravensbrück during the war, some 92,000 died there.

When Toto arrived at the camp in October 1944, the guards were preparing for the construction of a new gas chamber and a second crematorium. (Before Soviet troops liberated the camp in April 1945, the Germans gassed between 5,000 and 6,000 women and children at Ravensbrück.) Initially assigned to road repair, Toto lied to the guards and convinced them that she had training as a nurse. She was sent to work in the infirmary, among the camp’s sickest prisoners. There the German medical staff performed gruesome experiments on the dying, infecting open wounds with strange chemicals and amputating limbs to simulate soldiers’ battle scars. They carried out sterilization measures on women and young girls—Toto would later tell her friends she had been subjected to the “sterilizing projects of the camp”—and drowned or starved newborn babies in front of their mothers. Toward the end of the war, pregnant women were often forced to undergo abortions or, if Jewish, sent directly to the gas chambers.

During her seven months in the camp infirmary, Toto smuggled food to the sick at great personal risk and tried to ease their suffering. Meanwhile, Randolph Churchill had learned of her plight and sent her care packages full of onions and garlic to help ward off disease. In April 1945, shortly before the Russians arrived to free the camp, the Nazis agreed to release several hundred prisoners to the Swedish Red Cross. Toto was among them. She left the camp carrying one personal effect, a cardboard portrait a fellow prisoner had drawn of her. Relocated to the Swedish city of Göteborg, she found herself completely alone and psychologically fragile. Churchill came to her aid, flying to Sweden to provide her with money and clothing and to help her secure a passport. He also bought her a wig, to hide the fact that the Nazis had shaved her head in the camps. “I was lucky that Randolph Churchill came here,” Toto wrote to an old friend, “and as I am an old love of [his], he made a terrible fuss over me.”

For all her independence, Toto liked to be cared for, often by a powerful benefactor, and this penchant would bleed into her next relationship, the most enduring of all of her infatuations and one that defined the later years of her life. With money from the Red Cross as well as the modest pension she still received from Beaverbrook, Toto decided to settle in the Swiss lakeside town of Ascona, which served as a utopian retreat for hedonistic artist types. She drifted through a series of brief, tumultuous affairs, mostly with women, before meeting a severe, intense German art dealer who had arrived to vacation in Ascona in the winter of 1946.

Erica Brausen had played her own distinguished role in the Resistance. Under the code name “Beryl,” she ran an underground operation out of Majorca helping Jews and socialists evade Franco’s naval blockade and had ferried the writers Michel Leiris and Raymond Queneau to safety aboard a U.S. submarine. After moving to London in the early years of the war, Brausen had endured considerable prejudice due to her German roots, yet was widely known for her tireless work ethic and her unerring eye for talent. What’s more, she’d finally convinced a wealthy investor to help her open her own space, the Hanover Gallery in Mayfair, to exhibit the work of an unknown painter named Francis Bacon, whose violent canvases had caught her attention.

Entranced by Toto, Brausen brought her back to London and doted on her new amante, buying her sumptuous clothes and gifts despite a limited budget. By all accounts, Brausen was madly in love. Toto seemed also to have felt deep affection for Brausen, but she soon drifted back to her old coquettish ways. As Brausen turned a blind eye, Toto circulated in public with Randolph Churchill and even reunited with her former lover Max Aitken. But she also devoted herself to Brausen’s gallery, working her little black book to arrange glittering openings for the Hanover’s artists.

In the fall of 1949, Brausen and Toto promoted Bacon’s first exhibition at the gallery. Provocative and poisonous, Bacon had been shunned by most established dealers, but Brausen found in him a kindred spirit. Upon seeing his Painting (1946) for the first time, with its decaying animal carcasses and grimacing figures, Brausen offered to buy it on the spot. (Later she sold it to New York’s Museum of Modern Art.) Bacon’s shows at the Hanover, full of screaming popes and bloated self-portraits, shocked and titillated the tout-London. They also launched Bacon as one of the most important postwar painters and solidified Brausen’s reputation as a modern-art visionary. Soon, she was representing luminaries such as Max Ernst, Lucian Freud, Marcel Duchamp, and Alberto Giacometti.

While Bacon was the Hanover’s early star, he was also nearly its undoing. His addiction to casinos led him to beg Brausen for stupendous cash advances, which Toto would smuggle to him in Mediterranean gambling dens. Bacon secretly detested Toto for her hold over Brausen’s heart, calling the model the “Javanese whore” behind her back. Meanwhile, the Hanover’s main investor, who disliked both the attention-seeking artist and his morbid canvases, backed out, leaving Brausen in a precarious financial situation. The final blow came in 1958, when Bacon, facing mounting gambling debts, informed Brausen that he’d signed on with another gallery behind her back. Brausen and Toto considered suing, but Bacon had never signed a contract with them.

Perhaps to escape the indignity of losing Bacon to a rival—or perhaps to get Toto out of London and away from her many paramours—Brausen agreed to buy a property for the two women on the idyllic island of Panarea, just north of Sicily. Set among olive groves and rocky grottoes, the land became a sprawling retreat for Toto, Brausen, and their peripatetic social set. Toto decorated the house in a style that was at once minimalist and posh and hosted stately dinner parties for a never-ending stream of guests such as Bruce Chatwin and Alexander Calder. Brausen “went through all her money from the gallery, money that she had worked so hard to earn over the years” to support the Panarea property, one friend remembered.

While Toto settled into a lifestyle of drifting between Panarea and the continent’s cultural capitals, Brausen shuttled back and forth between the island and London, where the Hanover was flourishing. During the 1960s, everyone from Jean Paul Getty to the Beatles and Princess Margaret stopped by the space for its renowned exhibits. But the pressure of running the gallery and “maintaining Toto’s lifestyle” started to wear on Brausen. Already a dour woman, she turned into a scathing harridan with friends and associates alike. She also seemed to be growing more desperate about Toto’s affairs, the latest of which involved a strapping Sicilian carabiniere whom Toto had installed in the guest room of the women’s London apartment.

According to those close to the couple, Brausen found a doctor willing to prescribe heady amounts of morphine and became addicted to painkillers. In the spring of 1968, as Toto left town on another trip with her young Italian beau, Brausen was hospitalized with a serious ulcer. Within five years, the Hanover had closed its doors for good.

Remarkably, Toto and Brausen’s relationship managed to survive the gallery’s closing and their interpersonal turmoil, and they settled into a quiet retirement on Panarea, until they had to sell the property to pay for Brausen’s mounting medical problems. Toward the end, Brausen became secretive and controlling. When Toto had a stroke at the age of 82, Brausen squirreled her away in their London home, barring friends from visiting, firing a series of personal nurses, and subjecting Toto to the ministrations of a doctor reputed to be a medical charlatan. Toto’s health rapidly declined, and she died three months later.

In a ghastly scene, Brausen locked herself inside Toto’s bedroom for eight days with the body, draping the corpse in rosebuds and cuddling next to it. In death, if not life, Brausen finally had Toto to herself. She only relented when the state-appointed undertaker showed up to demand that she hand over the remains. It was a shocking conclusion to Toto’s long and remarkable life—though one that might have tantalized her old surrealist Parisian pals—and, if anything, serves to demonstrate the cultlike hold Toto had over her lovers. “Toto had the capacity to inflame people’s imaginations in spite of herself,” a friend told the biographer. Decades on, she still does.