As anyone who’s reading this story probably knows, Breaking Bad is a great television show. On Sunday night, it got even better.

We all have our favorite episodes of Breaking Bad. Some fans love “Face Off”—the one where Gustavo Fring takes his last, halting steps. Others prefer “Full Measure,” with Walter White and Jesse Pinkman teaming up, under immense pressure, to off Gale Boetticher.

But after a few minutes of stunned silence, I’ve come to the conclusion that “To’hajiilee”—the fifth episode of the final half-season, which aired Sunday on AMC—is the finest episode of Breaking Bad yet. The smartest. The most intense. And ultimately, the most devastating.

It makes me think Breaking Bad is hurtling toward as perfect an ending as anyone could conjure up on cable TV.

The last 10 minutes of “To’hajiilee” are what convinced me. When I visited creator Vince Gilligan on set in Albuquerque back in 2011, he confessed that he had originally conceived of the show as an homage, at least visually, to The French Connection. But the decision to shoot and set the series in New Mexico, where the tax breaks were bigger than California’s, got Gilligan thinking about Westerns. “Now I absolutely see Breaking Bad as a modern Western,” he said. “A man alone against the horizon, being tested, testing himself, testing his mettle.”

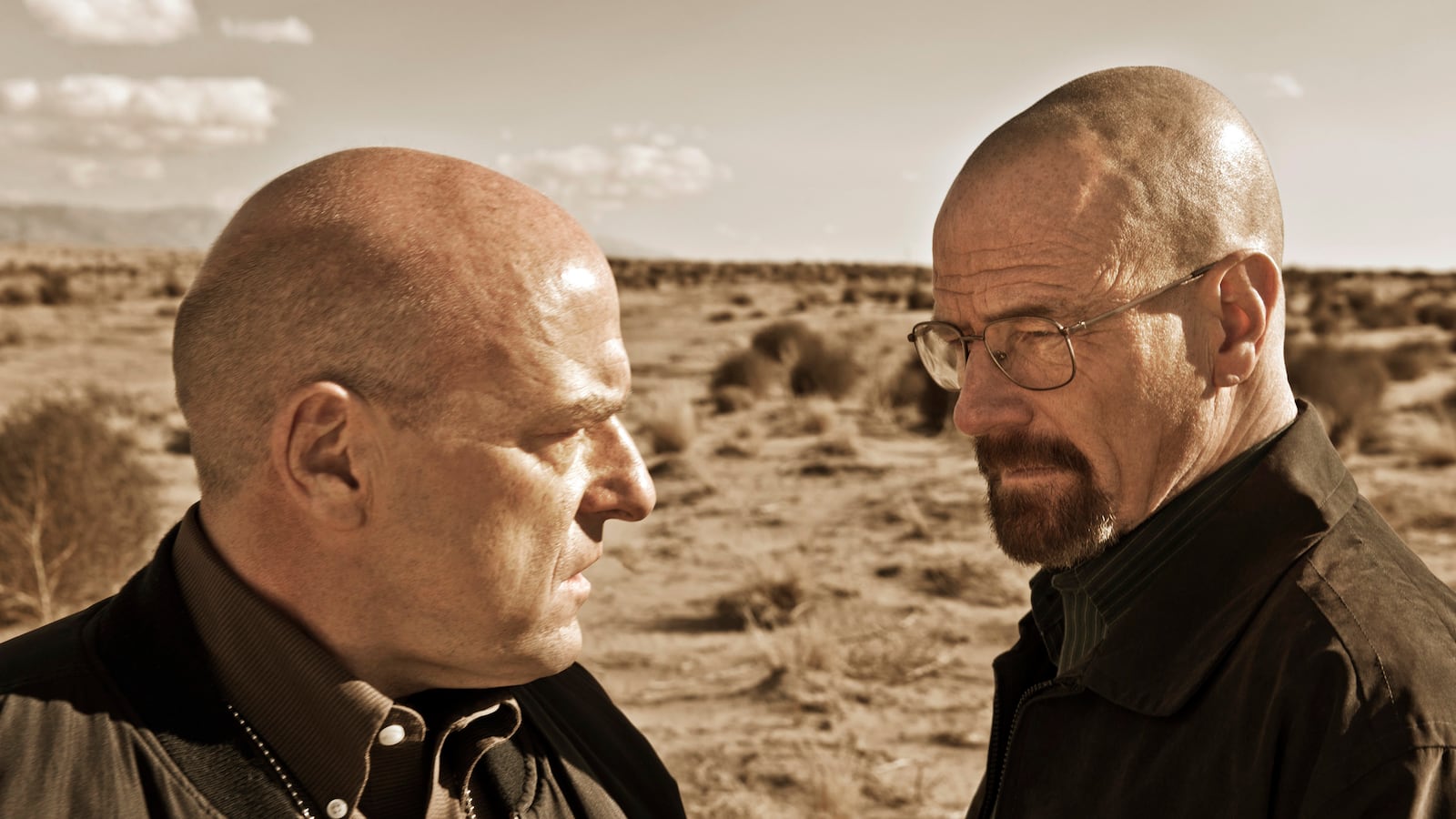

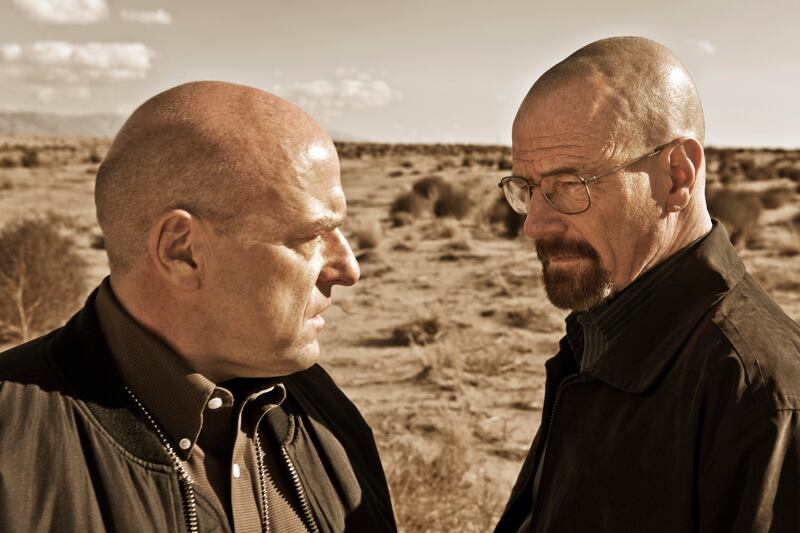

In the final act of “To’hajiilee,” that man seems to be Hank Schrader. Over the course of the episode, Hank constructs, sets, and finally springs an immaculate trap on his brother-in-law, Walt. First, with a staged photograph Hank tricks Walt into thinking that Jesse has found and is about to burn the seven barrels of meth money that Walt buried on the To’hajiilee Indian reservation, where he and Jesse cooked their inaugural batch. Then Hank trails Walt to the spot, reads him his Miranda rights, and calls in the DEA to dig up the cash, which is all the evidence they need to convict.

The plan works perfectly—at first. As staged by Gilligan, director Michelle MacLaren, and writer George Mastras, Walt’s arrest plays out like the conclusion of a classic Hollywood Western. The parched New Mexican moonscape. The good guy’s call for surrender, echoing off the crags. The bad guy coming out with his hands up. Justice itself unfolding, finally, in a slow, almost sanctified sequence, like stations of the cross: “Drop it. Hands up. Walk towards me slowly. Stop. Turn around. Lace your fingers behind your head. Walk backwards to me. Stop. Get on your knees.” And, above all else, the hero’s flinty satisfaction in getting his man.

After handcuffing Walt and tossing him in the back of his Suburban, Hank calls his wife, Marie. As they spoke, I could almost swear Hank was slipping into a John Wayne impersonation. Their dialogue was almost parodic—and deliberately so, I suspect.

“Baby, I got him, dead to rights,” Hank tells Marie.

“You got Walt?” Marie says, surprised.

“I got him in handcuffs as we speak. Want me to wave to him for ya?”

“Oh, my God,” Marie says, beginning to cry. “You did it. Thank God.”

“Things gonna be a little rough for the next couple weeks,” Hank grumbles. “But they’ll get better.” He hears Marie sniffling. “Baby, you OK?”

“I’m much better now,” Marie says, smiling through her tears.

“I gotta go. It may be a while before I get home. I love you.”

“I love you, too.”

And then Walt shouts, “HANK!”

In that split second, “To’hajiilee” turns—and Gilligan’s true vision for Breaking Bad becomes clearer than it’s ever been before. As I watched the final shootout—the hail of bullets buzzing back and forth between Hank and Agent Gomez on one side and Todd, Uncle Jack, and Uncle Jack’s neo-Nazi buddies on the other—I thought back to what Gilligan had actually said to me. “I absolutely see Breaking Bad as a modern Western,” he’d explained—emphasis on the modern. Hank isn’t the hero. There are no heroes. There is only Walter White and what he hath wrought.

And in the end, that’s what “To’hajiilee” is telling us. That Breaking Bad is about Walter White’s descent—not anyone else’s heroism. Throughout the series, Walt has drawn lines, moral boundaries, in the sand. At first he would refuse to cross them, but then, inevitably, he would give in, and that’s how we measured Mr. Chips’s transformation into Scarface (or Heisenberg). But the one line that Walt wouldn’t cross was family. The meth, the money, all of it—for family. That was the point. Without family, everything Walt had done—“the multiple murders, the ties to a white-supremacist prison gang, the largest meth operation in the Southwest,” as Hank put it Sunday night—would be for naught.

But morality isn’t a chemical equation, as much as Walter White might like to think he can calibrate and control it. In “To’hajiilee,” Gilligan & Co. demonstrate that principle to brutal effect. When Walt meets with Jack, he agrees to do two things he swore he would never do: kill Jesse (who, in his own words, “is like family”) and cook meth again (which will endanger Walt’s wife and children). Walt has his caveats, his rationalizations. He says Jesse’s death must be “quick and painless,” with “no suffering” and “no fear,” and he insists that he will only do “one cook, after the job”—that is, Jesse’s murder—“is done.”

But it’s useless. As palpable as Walt’s repugnance might be when he shakes Jack hand—Bryan Cranston is remarkable at conveying his character’s contradictory emotions in this scene—the deal kick-starts the crisp Rube Goldbergian plot machinery that makes the climactic showdown between Jack and Hank inevitable. Walt meant to kill Jesse. Now, a few scenes later, his own brother-in-law is in danger of being killed as a result.

Watching the shootout, I could barely breathe. The image that got me was one of the most poignant and terrifying ever to appear on a show with no shortage of either: Walt trapped in the back of a truck, powerless at last, his hands cuffed and his voice muffled, as the forces he has unleashed attempt to destroy the one thing he swore to protect. I can’t imagine a more effective way to dramatize the inescapable consequences of Walter White’s moral decline.

When I spoke last week to Dean Norris, the actor who plays Hank Schrader, he said something revealing about his boss. “Hank wants to be the guy to fight injustice,” Norris told me. “And I think Vince does, too. That’s part of Vince’s character. That there’s some sort of, you know, karmic justice in the world.”

At the time, I thought Norris’s remark might mean that Hank would somehow win in the end. But I don’t think that anymore—not after “To’hajiilee.” What I think now is that there won’t be any winners when Breaking Bad is over. Just one loser: Walter White—alone, dying of cancer, with seven barrels of money all to himself. And no family left to give it any meaning.

That is the kind of bleak karmic justice “To’hajiilee” gestures toward. We’ll find out far too soon, sadly, if I’m right.